A hundred years ago to the day, on 18 March 1922, M.K. Gandhi was sentenced to six years of imprisonment. The duration of the sentence had a curious symmetry to it. For it had taken six years of political activity in India, beginning with his controversial 1916 speech at the inauguration of the Banaras Hindu University in Banaras (now Varanasi), before Gandhi earned his rest in prison. Between 1919 and 1921, Gandhi fashioned a series of nationwide campaigns that decisively transformed the face of Indian politics.

The economic dislocation of the First World War, unhappy soldiers returning from the European front, and the effects of the 1918 pandemic all contributed to political turmoil in India, with an especially high level of public resentment in Punjab. To deal with the discontent, in 1919, the Raj introduced the draconian Rowlatt Act that allowed for indefinite detention and imprisonment without a trial.

Gandhi drew on an older Indian idea of a hartal, cessation of work, and led a highly successful Rowlatt satyagraha, which was the first truly pan-Indian mass political protest. The massacre at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar took place on its heels. For Gandhi, the administration condoning General Dyer’s actions and the British public approving it were more reprehensible than the act itself. He was now convinced that justice could never be obtained within the British Empire.

In an effort towards Hindu-Muslim unity, Gandhi made common cause with the ill-fated Khilafat campaign that sought to restore the Caliphate in Turkey. In 1920, Gandhi introduced the idea of Non-Cooperation. The British governed India, he argued, because Indians assented to such rule. Therefore it was imperative to withdraw public cooperation to an oppressive regime. Non-Cooperation was to include the boycott of government institutions such as courts and schools, and a refusal to serve as policemen or soldiers. Through the Congress, Gandhi also demanded redress of the grievances of the Punjab and the Khilafat movement.

In January 1922, Gandhi moved to Bardoli taluk in Gujarat to prepare for the next phase of the movement — a refusal to pay taxes. But on 4 February 1922, a mob set fire to a police station and burnt alive 22 policemen in Chauri Chaura in Gorakhpur district of the United Provinces. A horrified Gandhi suspended the planned civil disobedience campaign in Bardoli.[1] Gandhi’s unilateral decision was met by a “hurricane of opposition” from his colleagues and caused enormous heartburn. For all practical purposes, the first great upsurge of mass protest against colonial rule that began with the Rowlatt satyagraha came to an end.

Arrest and trial

Gandhi may have been non-violent, but he had been seething with rage against imperial hauteur and impunity and had written a number of increasingly militant essays in his weekly journal Young India, which almost dared the government to arrest him. His open declaration of disaffection with the government and call for soldiers to quit the army were affronts the Raj could barely stomach. Now, with serious discontent within the Congress over Gandhi’s leadership, the officials felt that they could make their move. After days of rumours, on the evening of 10 March 1922, the superintendent of police for Ahmedabad, Daniel Healy, arrived at Sabarmati Ashram with warrants for the arrest of Gandhi and Shankerlal G. Banker, the publisher of Young India.

Based on his writings, Gandhi was charged with sedition under Section 124 A of the Indian Penal Code, for exciting hatred and disaffection towards the government. The next morning, Gandhi and Banker told a startled magistrate that they did not need time to organise a legal defence as they intended to plead guilty to the charges. The trial for Rex Imperator v. M. K. Gandhi was set for 18 March 1922.

The trial being on a Saturday, the presiding judge Robert Broomfield played a relaxed round of golf before breakfast. Healy’s courtesy during Gandhi’s arrest and Broomfield’s nonchalance notwithstanding, the government had proceeded with extraordinary caution. The hearing was not held in the law courts but at the Circuit House because officials were worried about trouble during the trial. The unusual location allowed them to station an infantry battalion nearby. The trial passed off peacefully, but the fears were not unfounded. In 1919, Ahmedabad had witnessed major riots when it was rumoured that Gandhi had been arrested en route to Punjab. At that time, realising that a non-violent mass movement was taking a wrong turn, Gandhi had suspended the civil disobedience part of the Rowlatt satyagraha, calling it a Himalayan miscalculation.

The case for prosecution was made by the Advocate General Thomas Strangman, who arrived from Bombay that morning. As a young lawyer, Strangman had cut his teeth on a famous sedition case — the trial of Bal Gangadhar Tilak in 1897. Tilak’s prosecution had been based on English translations of his Marathi writings and his defence lawyer spent six days wrangling over the correctness of the rendering. Wiser from that experience, Strangman chose three English essays in Young India as evidence of Gandhi’s seditious behaviour.[2] But Strangman and his colleagues need not have worried. Unlike Tilak, Gandhi had no interest in legal tussles in a colonial court.

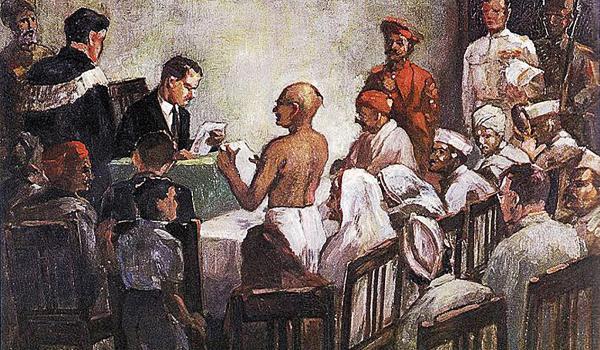

Broomfield entered the courtroom at noon. The charges were put to the defendants who pleaded guilty and all that remained to be done was pronouncing the sentence. Strangman objected as he wanted the sentencing to be based on an examination of the charges and not on a guilty plea of the defendants. Broomfield disagreed as the charges were clearly established without necessitating an examination, but allowed Strangman to make his comments. Strangman criticised Gandhi preaching non-violence while spreading disaffection against the government.

Gandhi responded by admitting that he had “been playing with fire” and would do so in the future “as my duty to my people” (‘The Great Trial’, Young India, 23 March 1922). He went on to famously declaim: “I wanted to avoid violence. I want to avoid violence. Non-violence is the first article of my faith. It is also the last article of my creed. But I had to make a choice.” The oppressive conditions in India were intolerable and needed a response.

Gandhi then proceeded to read a written statement that ranks as one of the most celebrated speeches of modern history. A great stylist of the English language, Gandhi’s writings dispensed with ornamentation or superfluous phrasing, thus achieving a luminous clarity. In the statement, Gandhi presented a tour d’horizon that traced his political evolution from a staunch loyalist to the implacable anti-colonial figure he had become. In terms that have a contemporary resonance, he decried the political emasculation of his people.

Section 124 A under which I am happily charged is perhaps the prince among the political sections of the Indian Penal Code designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen. Affection cannot be manufactured or regulated by law. If one has no affection for a person or system, one should be free to give the fullest expression to his disaffection, so long as he does not contemplate, promote or incite to violence.

In a further indictment of colonial misrule of India, he presented a charge-sheet against the economic exploitation of the masses.

No sophistry, no jugglery in figures can explain away the evidence that the skeletons in many villages present to the naked eye. I have no doubt whatsoever that both England and the town-dwellers of India will have to answer, if there is a God above, for this crime against humanity which is perhaps unequalled in history.

Recognising the import of what was to transpire that day, many of India’s political leaders were present in the makeshift courtroom to witness history in the making.[3] Gandhi joked that the courtroom looked like a family gathering. In delivering his judgment, Broomfield recognised that many regarded Gandhi as a “great patriot and a leader” and even Gandhi’s political opponents saw him “as a man of high ideals and of noble and even saintly life”. But the law was no respecter of persons and his only task was to consider the charges. Broomfield sentenced Gandhi to six years in prison, with the rider that he would be happy if the government found it fit to release Gandhi earlier. Banker was sentenced to a year in prison and a punitive penalty of Rs. 1,000 or an additional six months in default. The Great Trial, as it came to be known, lasted a mere hundred minutes. On his way to jail, Gandhi remained calm and cheerful. But, as Strangman noted “many wept” and he himself “was not wholly unaffected by the atmosphere” (1931, p. 143).

Viceroy Reading had exulted privately that not a dog barked when Gandhi was arrested and concluded that the leader’s career was “in the ditch.” But the true import of the proceedings in Ahmedabad was not lost on its Indian witnesses, and perhaps Broomfield himself. When Gandhi, the accused, entered the makeshift courtroom, the entire audience of 200 people spontaneously rose to its feet in respectful homage. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind that it was the British rule of India that was on trial that day.[4]

The Non-Cooperation Movement did not achieve its objective of ending India’s colonisation. But, as a recent centenary assessment argues, “It managed to hollow out British rule, shaking its authority to the core.” Crucially, Gandhi’s misgivings aside, “it was remarkably non-violent” (Hardiman 2021, 1). A watershed in the country’s history, the Non-Cooperation Movement introduced mass politics and large-scale satyagraha in India and laid the foundation for future struggles that led to freedom in 1947. In the process, Gandhi decisively changed the nature of Indian politics and would hold a commanding, if not unchallenged, position for decades to come.

But politics as commonly understood was not Gandhi’s primary concern. It was the transformation of Indian society through constructive work. A telling detail from the trial holds the key to this objective. When asked to state his profession, Gandhi said he was a “farmer and a weaver.” This was no idiosyncratic claim but an identification of his activities in that period. Agriculture and animal husbandry were important activities at Sabarmati. While the khadi movement is associated with spinning, in the early years the principal focus at Gandhi’s ashram was the weaving of cloth.

If satyagraha was a novel idea in Indian politics, so was Gandhi’s concern with the agrarian economy and the lives it supported. Through his championing of these new values, Gandhi transcended the limited aims and methods of an earlier generation of political leaders and attracted many to his camp.

We see this transformation in the life of his co-defendant, the much neglected Shankerlal Banker. Born to an affluent Bombay family in 1889, Banker had studied chemistry at St. Xavier’s College and joined the newly created Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore before moving to London in 1914 to train in leather technology. There he met Gandhi, but was unimpressed.

Back in Bombay, Banker became the secretary of the local branch of Annie Besant’s Home Rule League and also held a controlling interest in Young India. Working with Gandhi led to a sea change in Banker’s life. He abandoned his political activities in Bombay and moved, along with Young India, to Ahmedabad. Banker became deeply involved in Gandhi’s constructive programme, first in organising textile mill workers and later as a primary figure in the khadi movement through the All India Spinners Association. Like many other constructive workers who allied with Gandhi, for the quiet, unassuming Banker, there “were no prizes of political office waiting […] even through the avenue of prison” (Watson 1969, 50).[5]

The viceroy’s prognosis of the end of the Gandhi phenomenon proved incorrect. Gandhi was prematurely released from prison in 1924 following an emergency appendicitis. Over the next few years, he devoted himself to constructive work—khadi, abolishing of untouchability, and Hindu-Muslim unity—till he was drawn back into Congress politics towards the end of the 1920s. While it is beyond our scope here, the success and failures of the Non-Cooperation movement deeply shaped Gandhi’s approach in later years.

Conclusions

Contemporary India presents a number of ironic similarities with the state of affairs in 1922. Section 124 A remains on the books. Indeed, the ghost of Sidney Rowlatt haunts India today in the form of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Amendment Act and its ilk. The unity of hearts between Hindus and Muslims that Gandhi sought through the Khilafat movement, and strove for till he was assassinated, is in a shambles. Both the farmer and the weaver continue to struggle against challenging odds in an unequal world. A hundred years after the Great Trial, the “idea of India” seems to be on trial.

Notes

1. Chauri Chaura was the proverbial last straw as Gandhi had been increasingly dismayed by a number of episodes of violence in the preceding months, notably the Prince of Wales riots in Bombay in November 1921.

2. The essays were titled ‘Tampering with Loyalty’, ‘The Puzzle and its Solution’, and ‘Shaking the Manes’. A fourth, ‘Disaffection a Virtue’, was part of the original charge but was dropped before the trial.

3. These included Sarojini Naidu, Saraladevi Chaudhurani, Madan Mohan Malaviya, Abbas Tyabji, N.C. Kelkar, Tanguturi Prakasam, and Jawaharlal Nehru.

4. The Raj did not repeat its mistake of prosecuting Gandhi in a court of law. In later years, he would be detained under dubious 19th century legal provisions that allowed for indefinite imprisonment without a trial.

5. This paragraph draws on ‘Interview with Shankerlal G. Banker’ in Oral History Transcripts, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library.

References

Watson, Francis (1969). The Trial of Mr. Gandhi, London: Macmillan.

Strangman, Thomas (1931). Indian Courts and Characters, London: William Heinemann.

Hardiman, David (2021). Noncooperation in India: Nonviolent Strategy and Protest, 1920–22. New York: Oxford University Press.

(Venu Madhav Govindu is with the Department of Electrical Engineering, Indian Institute of Science. Courtesy: The India Forum. The India Forum is an independent online journal-magazine that seeks to widen and deepen our conversations on the issues that concern people.)