Part 1: Remote Working

A few weeks ago, the world’s richest man Elon Musk, Tesla CEO, told his employees that they must return to the office or get out of the company. Musk wrote in an email that everybody at Tesla must spend at least 40 hours a week in the office. “To be super clear: the office must be where your actual colleagues are located, not some remote pseudo office. If you don’t show up, we will assume you have resigned.” He then went on to praise workers in his Chinese factories for working until 3am in the morning if necessary.

In 2021, Goldman Sachs’s chief executive, David Solomon, said “remote work is not ideal for us, and it’s not a new normal”, and predicted that it would be “an aberration that we’re going to correct as quickly as possible”. A year later, however, less than half the bank’s employees were regularly turning up to its New York headquarters, forcing Solomon, to again plead with staff to come back. Again last year, Jamie Dimon, JP Morgan Chase’s chief executive, said working from home “doesn’t work for spontaneous idea generation. It doesn’t work for culture.” Dimon finally relented and said 40% of the bank’s 270,000 employees could work as few as two days a week from the office. In his annual letter to shareholders, he said “it’s clear that working from home will become more permanent in American business”.

Musk and these other bosses are like King Canute trying to turn back the tide. Since the pandemic, many workers are refusing to return to a full-time five-day week. More than a third of the UK’s office-based workforce is still working from home. In the UK, 23% of workers earning £40,000 or more are still working from home five days a week and a further 38% are in a hybrid pattern, splitting their time between the office and home.

Since the pandemic there has been the phenomenon of the so-called Great Resignation. The Great Resignation is the idea that a large number of people are quitting their jobs, and doing so because the pandemic gave them new perspective about their careers or were burned out during the pandemic. A Microsoft global survey of more than 30,000 workers showed that 41% were considering quitting or changing professions, and a study from HR software company Personio of workers in the UK and Ireland showed 38% of those surveyed planned to quit in the next six months to a year. In the US alone, April saw more than four million people quit their jobs, according to a summary from the US Department of Labor – the biggest spike on record.

This is not a uniquely American phenomenon. China’s “lie flat” movement, in which young people are turning their backs on the daily grind, is gaining popularity. In Japan, known for long office hours, the government has proposed a four-day working week.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the ILO estimated that 7.9% of the world’s workforce (260 million workers) worked from home on a permanent basis. Although some of these workers were old-fashioned ‘teleworkers’, most were not, as the figure includes a wide range of occupations including industrial outworkers (e.g. embroidery stitchers, beedi rollers), artisans, self-employed business owners and freelancers, in addition to employees.

Employees accounted for one out of five home-based workers worldwide, but this number reaches one out of two in high-income countries. Globally, among employees, 2.9% were working exclusively or mainly from their home before the COVID-19 pandemic. But close to 18% of workers work in occupations and live in countries with the infrastructure that would allow them to effectively perform their work from home (ILO 2020).

This estimate matches others for the UK, namely 18% of jobs in the UK – 5.9 million in total – are ‘anywhere’ jobs. Looking at the occupational breakdown, anywhere jobs are predominantly in professional (36%), technical (30%), and administrative (24%) occupations. Of all anywhere jobs, 1.7 million (28%) are in the finance, research, and real-estate sectors, and 1.1 million (18%) are in transport and communication.

Here are the numbers on job postings that were geared towards remote work:

| Industry | % Remote (Sept 2020) | % Remote (Sept 2021) | Change |

| Software & IT Services | 12.5% | 30.0% | 17.5 |

| Media & Communications | 12.5% | 21.3% | 8.8 |

| Wellness & Fitness | 3.3% | 21.2% | 17.9 |

| Healthcare | 3.2% | 14.4% | 11.2 |

| Nonprofit | 4.6% | 14.1% | 9.5 |

| Hardware & Networking | 2.2% | 12.9% | 10.7 |

| Corporate Services | 5.2% | 9.5% | 4.3 |

| Education | 9.4% | 8.8% | -0.6 |

| Entertainment | 3.0% | 7.7% | 4.7 |

| Finance | 1.8% | 6.5% | 4.7 |

| Consumer Goods | 2.2% | 6.0% | 3.8 |

| Recreation & Travel | 0.2% | 3.7% | 3.5 |

| Manufacturing | 1.4% | 3.0% | 1.6 |

| Energy & Mining | 1.0% | 2.7% | 1.7 |

| Retail | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.2 |

But the move to remote working or four-day week is still being fought against by most bosses. Why? For two reasons. The usual one offered is that when staff are in the office, they are ‘more productive’. It’s harder to collaborate and be creative with colleagues over endless video calls. That’s not the view of many workers, however, who say they get much more done at home without gossiping and other office distractions. In 2015, a study of 16,000 call centre staff found that those who worked from home (WFH) were 13% more efficient than their office-based colleagues. The WFH team were more productive as they took fewer breaks, were sick less often and put in more calls an hour as they didn’t get distracted by tea breaks and water-cooler moments.

The spatial freedom to work outside the office, supercharged by the pandemic, has increased the temporal freedom to work at any time. “Asynchronous work” is the new buzzword in HR and management circles. This has advantages: it avoids the unpleasant synchrony of everyone cramming on to trains every morning and evening and allows people to fit work around other priorities or responsibilities.

But there are downsides too. A study published in 2017 of workers in 15 countries found that the impact of remote work on work-life balance was “highly ambiguous”: workers reported more time with their families, but also an increase in working hours and blurred boundaries between paid work and personal life.

There are also concerns about the potential mental health impacts of working from home. Research by management consultancy firm McKinsey found that working from home had actually increased “burnout” rates among all employees as they struggled to juggle their careers and family lives, and this was particularly the case for women. The survey of 65,000 employees found that the gap between male and female burnout rates nearly doubled, with 42% of women reporting burnout compared to a third of men.

But the real reason for opposition by employers is not just lower productivity but that management starts to lose control over its employees, both in terms of time and in dictating activity. The oppressive boss-employee relationship begins to weaken. And of course, there is the question of money. The London law firm Stephenson Harwood is allowing its staff to work from home 100% of the time – but only if they take a 20% pay cut. “Like so many firms, we see value in being in the office together regularly, while also being able to offer our people flexibility,” a spokesperson said. On the popular law industry website RollOnFriday, one Stephenson Harwood lawyer said the “100home80pay” policy was “a total gamechanger”. “I get to live in Bath and work for a City firm”, earning more than at their former regional firm “even after the 20% discount”.

These objections by the bosses to remote working and a shorter working week are now to be tested in a new pilot scheme. More than 3,000 workers at 60 companies across Britain will trial a four-day working week, in what is thought to be the biggest pilot scheme to take place anywhere in the world. Joe O’Connor, the chief executive of 4 Day Week Global, said there was no way to “turn the clock back” to the pre-pandemic world. “Increasingly, managers and executives are embracing a new model of work which focuses on quality of outputs, not quantity of hours,” he said. “Workers have emerged from the pandemic with different expectations around what constitutes a healthy life-work balance.”

That sounds great for the professional classes in finance, law and technology. Overall, 48% (2.8 million) of those in anywhere jobs have a degree. Indeed, 20% of people educated to degree level or higher in the UK are working in an anywhere job. But the majority of workers are not needed in such anywhere jobs. Most work in jobs that pay poorly and require full-time activity away from the hone. In the UK, just 6% of people earning £15,000 or less are working from home every day, and only 8% have hybrid working privileges.

The British Trades Union Congress (TUC) has warned that working from home risks creating a “new class divide” as frontline workers in supermarkets and hospitals, mechanics and other customer-centric jobs do not have the option to work from home. Frances O’Grady, the TUC general secretary, says: “Everyone should have access to flexible working. But while home working has grown, people in jobs that can’t be done from home have been left behind. They deserve access to flexible working, too. And they need new rights to options like flexitime, predictable shifts and job shares.”

The reality is that for most workers the decline of the “9 to 5” has been under way for decades. In 2010-11, 20 per cent of employees in the US worked more than half their hours outside the standard hours of 6am to 6pm or on weekends. A vast survey of workers across the EU in 2015 found about half worked at least one Saturday a month, almost a third worked at least one Sunday, and roughly a fifth worked at night. And this is mostly at the workplace not at the home.

One common shift pattern for production and warehouse workers today is to work four 12-hour days, have four days off, then work four nights, then have another four days off. Another is to work eight-hour shifts on rotation. As one current UK job advert for a warehouse job explains: “The hours of work are: 6am to 2pm, 2pm to 10pm, 10pm to 6am. You will work one week on one shift and then rotate, therefore flexibility to cover all shifts is required.” No home working there.

Factories and warehouses aren’t the only workplaces that run around the clock. Shift work is common for doctors, nurses, carers, drivers and security guards, among others. It appears to be on the rise. In 2015, 21 per cent of workers in the EU reported doing shift work, up from 17 per cent a decade earlier. While shift work suits some people, the evidence suggests it damages their health, especially if they rotate between days and nights. Twelve-hour shifts, rotating shifts and unpredictable schedules are associated with higher risk of mental illness, cardiovascular problems and gastrointestinal problems.

Shift work can also harm family life. “Divorce is pretty bad. We see a lot of divorce, just due to the fact that families, especially young couples, you’re away from your family [for] 12 hours, and then when you go home after a 12-hour shift, you just want to sleep,” one manager in a US manufacturing plant told academics studying the impact of shift work. A worker in the same study said: “It changes our time with our family. It changes our time with our social life and church and community groups. All those things that you would like to be involved with.”

Remote working may be here to stay; and many employers may agree to a four-day week (but almost certainly only if ‘productivity’ rises enough to justify it and probably with a pay cut). But the daily (and nightly) drudge on barely acceptable rates of pay will continue for most workers.

Part 2: Working Long and Hard

In the part above, I looked at the impact of working from home and remote work which has mushroomed since the COVID pandemic.

In this second part, I want to consider the impact of work on people’s lives and health and how that will pan out over the next few decades. Marx once said,

“The less you eat, drink and buy books; the less you go to the theatre, the dance hall, the public house; the less you think, love, theorize, sing, paint, fence, etc., the more you save—the greater becomes your treasure which neither moths nor rust will devour—your capital. The less you are, the less you express your own life, the more you have, i.e., the greater is your alienated life, the greater is the store of your estranged being.” (Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts 1844)

I take this to mean that, while human (both mental and manual) labour has its satisfactions, work for most people for most of the time, is really toil. People do not live to work (although sometimes people say they do) but work to live. They have little time to develop interests and their imaginative potential.

Much is made of how annual working hours have declined over the last century. The working week has steadily fallen, the argument goes–things are getting better. No more children working in mines and factories; two or three days a week not working etc.

But this hides much of the reality. First, it is not true that children are not being put to work in the fields, mines and factories of the Global South in large numbers; or that ‘slave labour’ is not operating as servants for the rich in their homes or in migrant dominated jobs. Second, while total hours may have declined on official figures, there are sizeable sections of the workforce still enduring long hours and intensive work. Around 500 million people in the world are working at least fifty-five hours per week, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and International Labour Organization (ILO).

In recent years, the trend toward shorter working hours has halted, and in some cases, reversed. A 2018 ILO report found that there has been a bifurcation of working hours,

with substantial portions of the global workforce working either excessively long hours (more than 48 hours per week), which particularly affects men, or short hours/part-time work (less than 35 hours per week), which predominantly impacts women.

The link between overwork and underwork, or unemployment, is not new. As Karl Marx describes it in Capital,

the overwork of the employed part of the working class swells the ranks of the reserve while, conversely, the greater pressure that the reserve by its competition exerts on the employed workers forces them to submit to over-work and subjects them to the dictates of capital.

Jon Messenger, the author of the 2018 ILO report, points out that there has been “a diversification of working time arrangements.” He writes, “with a movement away from the standard workweek consisting of fixed working hours each day for a fixed number of days and towards various forms of ‘flexible’ working time arrangements (e.g. new forms of shift work, hours averaging, flexi-time arrangements, compressed workweeks, on-call work).” With these arrangements comes the expectations that one always be on call–‘Rise and Grind 24/7’.

What is striking about this trend is that it’s happening to everyone. Studies have found work intensification among managers, nurses, aerospace workers, meat processing workers, schoolteachers, IT staff and carers. There is also evidence of work intensification in Europe and the U.S.. “It’s not just the Amazon production line person who’s had their work intensified, it’s the London commuter and the new solicitor,” says Francis Green, a professor at UCL who has studied the phenomenon for years. According to an analysis by the UK’s Resolution Foundation think-tank, just over two-thirds of employees in the top quarter of the pay ladder in the UK said they worked “under a great deal of tension”. The same was true for half of those in the bottom quarter for pay, and this latter group has experienced the biggest increase in tension since the 1990s.

Here are some explanations of why work has intensified for so many. In the 1990s, people said their “own discretion” was the most important factor in how hard they worked. Now they are more likely to cite “clients or customers.” In a world of instant communication, many workers now feel they have to respond quickly to consumer or client demands. That goes for the banker working on a big merger as well as the Uber Eats driver he summons to bring him a burger.

Another possible explanation is that employers have simply cut headcounts to save costs without coming up with more efficient ways of doing things. This will no doubt resonate with public sector workers everywhere who have experienced a decade or more of government spending cuts.

Some companies have also harnessed technology to extract more effort from staff. More workplaces like warehouses have become partially automated, which means workers must keep pace with machines. Other workers are now easier to monitor. Witness the growth of software which tracks employees’ keystrokes, measures their breaks and sends nudges if they stray on to non-work-related sites. Taylorism as it used to be called is still alive and well. (Taylorism is the so-called science of dividing specific tasks to allow employees to complete assignments as efficiently as possible. The practice of Taylorism was first developed by Frederick Taylor who claimed that it would lead to the most efficient practices in the workforce.)

A fourth possibility is that email and instant messaging platforms simply tire people out mentally. It is hard to focus when constantly interrupted, which might leave workers feeling as if they are working hard and fast even if they aren’t

Jamie McCallum in his excellent book Worked Over: How Round-the-Clock Work Is Killing the American Dream (Basic Books, 2020), points out that actually the hours of all wage and salary workers in the U.S. have increased by 13 percent since 1975, which is about five extra workweeks per year. And it’s the hours of low-wage workers, who are disproportionately women, that have increased the most. And this in the period of stagnating wages, rising hours, and declining union density. More intensified work has gone along with rising income inequality.

If wages are stagnant, then the main way that working-class and even middle-class people for the most part get more money is by working longer hours. An EPI report highlights trends in annual work hours among American prime-age workers between 1979 and 2016. As wage inequality has grown over the last four decades, we observe two very different responses when it comes to work hours. On one hand, workers are working many more hours a year, perhaps in part to compensate for tepid, and in some instances declining, hourly wage growth. On the other hand, a growing number of workers have become disconnected from the labour force, by not working at all over the course of an entire year.

Work hours have typically grown most among the lowest earners and those working the fewest hours.

Long working hours are killing more than 700,000 people per year. According to WHO and the ILO, long hours resulted in 745,194 deaths in 2017, up from roughly 590,000 in 2000. Of these deaths, 398,441 are attributable to strokes and 346,753 to heart disease. This puts those working these hours at an estimated 35 percent higher risk of strokes and 17 percent higher risk of heart disease compared to people working thirty-five to forty-hour weeks. Men and middle-aged adults are particularly exposed and the problem is most prevalent in Southeast Asia. So while working harder doesn’t seem to be making us richer, it does appear to be making us sicker.

A new study by academics Tom Hunt and Harry Pickard suggests that “working with high intensity” increases the likelihood of people reporting stress, depression and burnout. They are also more likely to work when sick. Data from the UK Health and Safety Executive shows that the proportion of people suffering from work-related stress, depression or anxiety was rising even before the pandemic hit. Indeed, Marxist health economist Jose Tapia found counter-intuitively that it was in in periods of economic boom and full employment that mortality rates rose because of the stress from work, while it fell in recessions as people may become unemployed but suffered less stress from not working.

This raises the question of productivity. Work intensification is coinciding not with rising productivity as employers expect but slowing productivity growth. Taylorism may still be alive in exploiting the labour force, but it does not deliver for capital. Why is that? One argument was presented by the late anthropologist and radical David Graeber, who argued that people were asked to loads of what he called ‘bullshit’ jobs. This theory is that a large and rapidly increasing number of workers are undertaking jobs that they themselves recognise as being useless and of no social value. So they do not work well.

However, that theory has been contested by recent research. This finds that the proportion of employees describing their jobs as useless is low and declining and bears little relationship to Graeber’s predictions. Much more relevant is Marx’s own concept of alienation. Marx argued that labour under capitalism is inherently alienating as it blocks individuals’ essential need for self-realisation. However, for Marx this was not the result of individuals being engaged in activity that was of no social value but rather because capitalist social relations frustrated the free development of human abilities in spontaneous activity.

Unlike the BS jobs theory, alienation is not premised on the view that the work being undertaken is inherently pointless and of no value. Instead, it highlights the importance of the social relations under which work is undertaken and the degree to which they constrain the ability of workers to affirm their sense of self through the development and recognition of skills and abilities. (Magdalena Soffia et al., Alienation Is Not ‘Bullshit’: An Empirical Critique of Graeber’s Theory of BS Jobs)

So the social solution to work stress and exploitation is not to stop people doing ‘bullshit jobs’ and instead give them benefits not to work. The answer is to overturn those social relations in which people’s work is devalued by toxic workplace cultures that leave workers feeling their labour is pointless and of no use. The phenomenon of meaningless work illuminates the contradiction at the heart of capitalism itself.

Long hours at tedious jobs can be avoided if workers had greater control over their employment, conditions and schedules. Cooperative work could replace authoritarian dominance, Taylor style, by bosses. Machines can be used to increase opportunities to reduce working time and develop innovations, and not designed to dictate hours and intensity of work. It’s capitalist social relations in the workplace that destroys innovation, cooperation and people’s health, not the jobs as such themselves. The future of creative work rather than destructive toil depends on ending capitalist operations in the workplace ie workers control.

Part 3: Automation

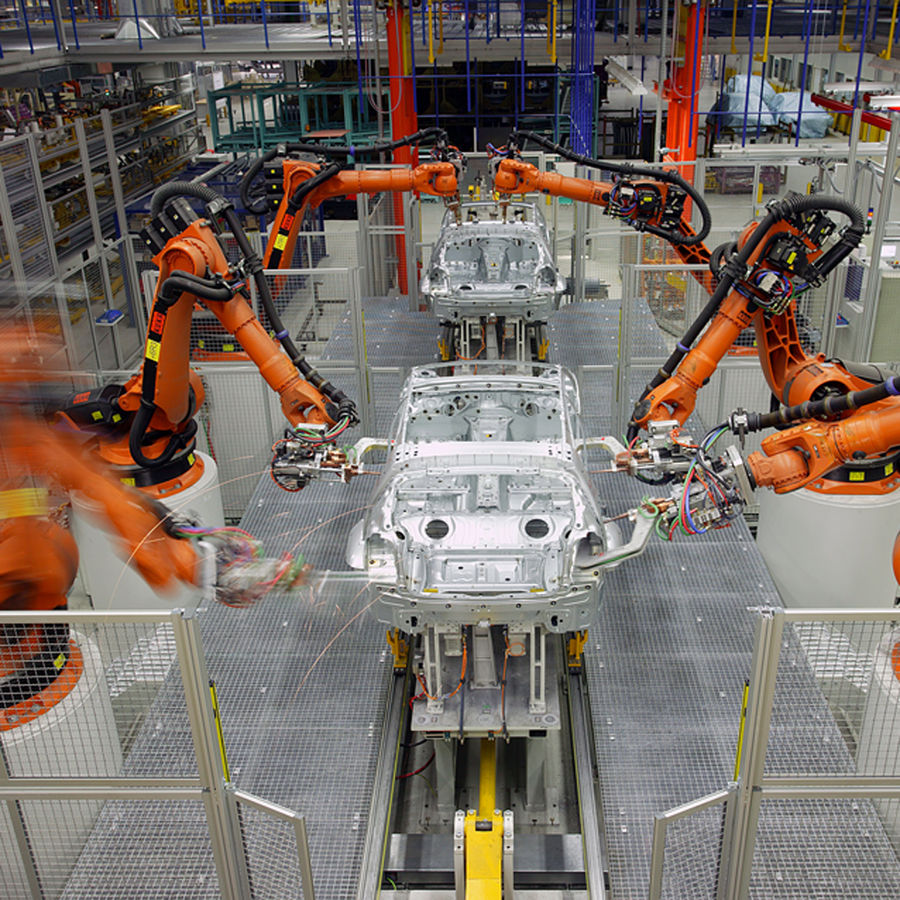

In this third part, I want to deal with the impact of automation, in particular robots and artificial intelligence (AI) on jobs. I have covered this issue of the relationship between human labour and machines before in earlier articles, including robots and AI. But is there anything new that we can find after the COVID slump?

The leading American mainstream expert on the impact of automation on future jobs is Daron Acemoglu, Institute Professor at MIT. In testimony to the U.S. Congress, Acemoglu started by reminding Congress that automation was not a recent phenomenon. The replacement of human labour by machines started at the beginning of the British Industrial Revolution in the textile industry, and automation played a major role in American industrialization during the 19th century. The rapid mechanization of agriculture starting in the middle of the 19th century is another example of automation.

But this mechanisation still required human labour to start and maintain it. The real revolution would be if automation became not just human controlled machinery, but also robots in manufacturing and software-based automation in clerical and office jobs that required not only less human labour, but could totally replace it. This form of automation started to happen from the 1980s as capitalists looked to boost profitability by shedding human labour in droves. Whereas, previous mechanisation not only shed jobs, often it also created new jobs in new sectors, as Engels noted in his book, The Condition of the Working Class in England (1844).

Acemoglu reckons modern automation, particularly since the Great Recession and the COVID slump, is even more deleterious to the future of work. “Put simply, the technological portfolio of the American economy has become much less balanced, and in a way that is highly detrimental to workers and especially low-education workers.” He reckoned that more than half, and perhaps as much as three quarters, of the surge in wage inequality in the U.S. is related to automation. “For example, the direct effects of offshoring account for about 5-7% of changes in wage structure, compared to 50-70% by automation. The evidence does not support the most alarmist views that robots or AI are going to create a completely jobless future, but we should be worried about the ability of the U.S. economy to create jobs, especially good jobs with high pay and career-building opportunities for workers with a high-school degree or less.” His analysis of automation’s effects in the U.S. also applied to the rest of the major capitalist economies.

The other significant conclusion that Acemoglu reached was that not all automation technologies actually raise the productivity of labour. “Those that reduce costs and boost productivity generate a set of compensating changes, for example, expanding employment in non-automated tasks. On the other hand, if automation is “so-so”–meaning that it generates only minor productivity improvements–then it creates all the displacement effects but little of the compensating benefits.” Indeed, as the U.S. economy has shifted more and more into automation, it has gone less into socially beneficial types of automation. Indeed, Acemoglu reckons that the drive for extra profits from automation by leading companies can lower productivity growth. That’s because companies mainly introduce automation in areas that may boost profitability, like marketing, accounting or fossil fuel technology, but not raise productivity for the economy as a whole or meet social needs.

As Acemoglu explained to the U.S. Congress: “American and world technology is shaped by the decisions of a handful of very large and very successful tech companies, with tiny workforces and a business model built on automation.” And while government spending on research on AI has declined, AI research has switched to what can increase the profitability of a few multi-nationals, not social needs: “government spending on research has fallen as a fraction of GDP and its composition has shifted towards tax credits and support for corporations. The transformative technologies of the 20th century, such as antibiotics, sensors, modern engines, and the Internet, have the fingerprints of the government all over them. The government funded and purchased these technologies and often set the research agenda. This is much less true today.”

In the U.S., software and equipment are taxed close to zero and in some cases, corporations can even get a net subsidy when they invest in such capital. This generates a powerful motive for ‘excessive automation’ where companies can save money when they install machinery to do the same jobs as workers and lay off their employees, because the government subsidizes their investments and taxes what they pay in wages.

The result of automation in the last 30 years has been rising inequality of incomes. There are many factors that have driven up inequality of incomes: privatisation, the collapse of unions, deregulation and the transfer of manufacturing jobs to the global south. But automation is an important one. While trend GDP growth in the major economies has slowed, inequality has risen and many workers–particularly, men without college degrees–have seen their real earnings fall sharply.

Even U.S. treasury secretary Janet Yellen admitted that recent technologically driven productivity gains might exacerbate rather than mitigate inequality. She pointed to the fact that, while she reckoned that the “pandemic-induced surge in telework” might ultimately raise U.S. productivity by 2.7%, those gains will accrue mostly to upper income, white-collar workers, just as online learning has been better accessed and leveraged by wealthier, white students. Indeed, increased online learning is another pandemic-induced technological shift that is likely to widen the educational achievement and productivity gap between upper-income children relative to those who are lower-income and minority.

Jobs that require less educational and technical skills will disappear and be replaced by those that do. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projects there will be 11.9 million new jobs by 2030, an overall growth rate of 7.7%. But while some sectors will expand jobs, others will be decimated.

These are fastest-growing occupations in the U.S..

| change, 2020–2030P | change, 2020-2030P | |

| Wind turbine service technicians | 68.2% | 4,700 |

| Nurse practitioners | 52.2% | 114,900 |

| Solar photovoltaic installers | 52.1% | 6,100 |

| Statisticians | 35.4% | 14,900 |

| Physical therapist assistants | 35.4% | 33,200 |

| Information security analysts | 33.3% | 47,100 |

| Home health and personal care aides | 32.6% | 1,129,900 |

| Medical and health services managers | 32.5% | 139,600 |

| Data scientists and mathematical science occupations, all other | 31.4% | 19,800 |

| Physician assistants | 31.0% | 40,100 |

Nine of the top 20 fastest growing jobs are in healthcare or related fields, as the baby by population ages and chronic conditions are on the rise. Home health and personal care workers who assist with routine healthcare tasks such as bathing and feeding, will account for million new jobs in the next decade. This will be almost 10% of all new jobs created by 2030. Unfortunately, these workers are the lowest paid on the list.

Then these are the occupations that will decline.

| change, 2020–2030P | change, 2020-2030P | |

| Word processors and typists | -36.0% | -16,300 |

| Parking enforcement workers | -35.0% | -2,800 |

| Nuclear power reactor operators | -32.9% | -1,800 |

| Cutters and trimmers, hand | -29.7% | -2,400 |

| Telephone operators | -25.4% | -1,200 |

| Watch and clock repairers | -24.9% | -700 |

| Door-to-door sales workers, news and street vendors, and related workers | -24.1% | -13,000 |

| Switchboard operators, including answering service | -22.7% | -13,600 |

| Data entry keyers | -22.5% | -35,600 |

| Shoe machine operators and tenders | -21.6% | -1,100 |

Eight of the top 20 declining jobs are in office and administrative support. These occupations currently make up almost 13% of employment in the U.S., the largest of any major category. Jobs involved in the production of goods and services, sales jobs, are also seeing declines. In all cases, automation is likely the biggest culprit. For example, software that automatically converts audio to text will reduce the need for typists. Seventeen of the top 20 fastest growing jobs have a median salary higher than $41,950 median salary for all jobs in total. Most also require post-secondary schooling. The opportunities are replacing jobs that only required a high school diploma.

That’s one aspect of the impact of automation on future work. The flipside of this is that automation and robots do not necessarily reduce the labour time involved in producing the things and services that modern societies need.

In March 2018, Flippy, a burger-flipping robot, was rolled out at the Pasadena location of fast-food chain CaliBurger, in California, to great fanfareand numerous headlines. But Flippy was retired after one day of work. CaliBurger’s owners blamed Flippy’s failure on their human employees: workers, they explained, were simply too slow with tasks such as dressing the burgers, causing Flippy’s meaty achievements to pile up. However, a few discerning journalists had previously noted Flippy’s numerous errors in the relatively simple task that gave the robot its name. Flippy just wasn’t very good at its job.

Investigating grocery store self-checkout, researchers found that customers hated and avoided the technology. In response, management cut staff to make lines so unbearable that customers gave up and used the machines instead. Even then, cashiers were still required to assist and monitor transactions; so rather than reduce workload, the technologies were intensifying the work of customer service. Self-checkouts are an example of how rather than abolishing work, automation proliferates it. By isolating tasks and redistributing them to others expected to do it for free, digital technologies contribute to overwork.

Indeed, AI regularly fails at tasks simple for a human being, such as recognizing street signs—something rather important for self-driving cars. But even successful cases of AI require massive amounts of human labour backing them up. Machine learning algorithms must be “trained” through data sets where thousands of images are manually identified by human eyes.

Getting AI systems to function smoothly requires astonishing amounts of “ghost work”: tasks performed by human workers who are kept away from the eyes of users, and off the company books. Ghost work is “taskified”—broken down into small discrete activities, “digital piecework” that can be performed by anyone, anywhere for a tiny fee.

Big Tech has a particular approach to business and technology that is centered on the use of algorithms for replacing humans. It is no coincidence that companies such as Google are employing less than one tenth of the number of workers that large businesses, such as General Motors, used to do in the past. This is a consequence of Big Tech’s business model, which is based not on creating jobs but automating them.

That’s the business model for AI under capitalism. But under cooperative commonly owned automated means of production, there are many applications of AI that instead could augment human capabilities and create new tasks in education, health care, and even in manufacturing. Acemoglu suggested that,

rather than using AI for automated grading, homework help, and increasingly for substitution of algorithms for teachers, we can invest in using AI for developing more individualized, student-centric teaching methods that are calibrated to the specific strengths and weaknesses of different groups of pupils. Such technologies would lead to the employment of more teachers, as well as increasing the demand for new teacher skills–thus exactly going in the direction of creating new jobs centered on new tasks.

There is also a more sinister aspect to AI. Employers have always tried to employ ‘big brother’ methods to control and discipline their workforces. Amazon is installing high-tech cameras inside supplier-owned delivery vehicles. Workers say the cameras are an invasion of privacy as well as a safety hazard. But Karolina Haraldsdottir, a senior manager of the last-mile delivery operation at Amazon, emphasizes that the cameras are meant “as a safety measure, intended to reduce collisions.” The company cited a pilot roll-out of the cameras from last year, which they say saw accidents drop by 48%.

Workers disagree. The installation of Driveri is in keeping with Amazon’s roll-out of similar camera monitoring among its long-haul trucking operation. “I am now driving around with an inscrutable black box that surveils me and determines whether I keep my job,” says a delivery driver in Washington. While he says he sees how, in theory, some of the metrics are justifiable – “you don’t want your drivers Tokyo Drifting through neighbourhoods” – in reality, aggregated on top of the layers of surveillance to which drivers already feel subject, it is “stifling, unnecessary, and ridiculous.” “We’re all just out here trying to do our best, but we also have to contend with knowing that each week, computers spit out metrics for us which require multiple pages to properly display, and a drop in those abstract numbers could lose us jobs,” he says. “All I want to do is deliver my damn packages and go home, man.”

Automation under capitalism means significant job losses among those without educational qualifications (education is now more and more expensive) and hits the lowest paid. Under capitalism, the aim is to boost profitability (and not even productivity, as much of automation can actually reduce productivity). And it is being used to control and monitor workers rather than help them achieve their tasks. Only the replacement of the profit motive could allow automation and robotics to deliver real benefits in shorter working hours and increased social goods.

(Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has also been a political activist in the labour movement for decades. Since retiring, he has written several books. Courtesy: Michael Robert’s blog.)