Sam Biddle

The state department has a new vision for a “clean” internet, by which it means a China-free internet. This new ethno-exclusive network “is the Trump Administration’s comprehensive approach to guarding our citizens’ privacy and our companies’ most sensitive information,” by ensuring that China won’t be able to do a litany of subversive and violative things with technology that the U.S. and its allies have engaged in for years. As a policy document it’s nonsensical, but as a moral document, a piece of codified hypocrisy, it’s crystal clear: If there’s going to be a world-spanning surveillance state, it better be made in the USA.

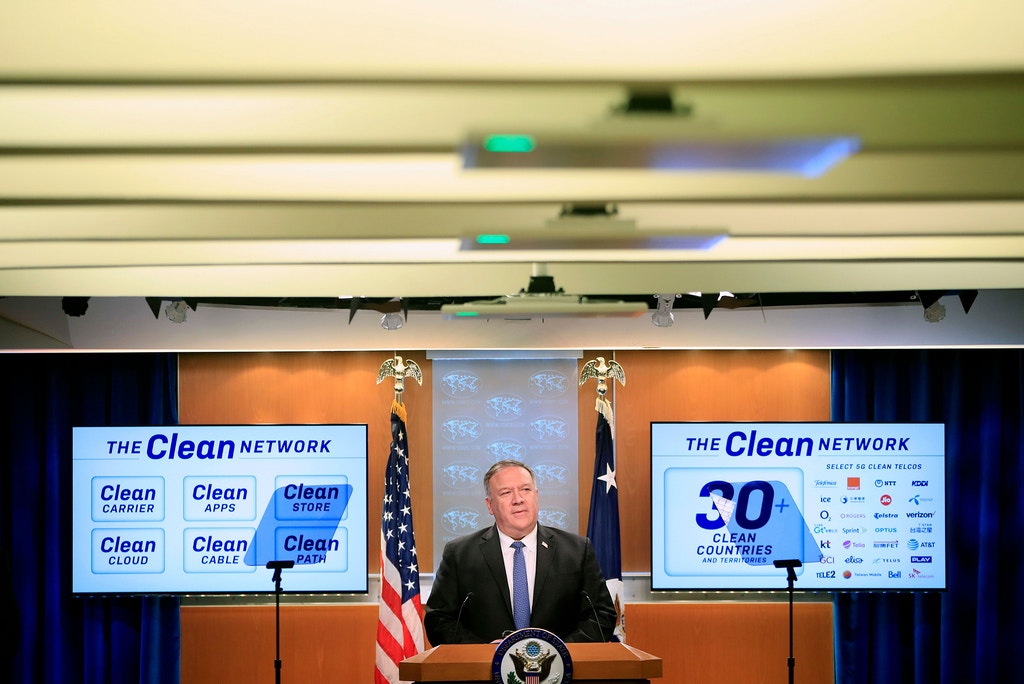

A statement from Secretary of State Mike Pompeo includes a five-pronged plan for beating back Red China’s attempts to siphon and abuse your data: Working to keep Chinese phone carriers (presumably compromised by Beijing) out of U.S. markets, to have privacy-violating Chinese apps kicked off American app stores, to remove U.S. apps from app stores run by Chinese companies, to keep U.S. citizens’ data off of Chinese cloud servers “accessible to our foreign adversaries,” and to ensure that the undersea cables that ferry internet signals between continents aren’t secretly tapped by eavesdropping Chinese intelligence services.

The real question, even more than how could any of this practically be accomplished by State Department diktat, is: Why should anyone in the world take the initiative seriously? How can any network fondled for decades by American spy agencies be considered clean? The absolute gall of the United States in condemning “apps [that] threaten our privacy, proliferate viruses, and spread propaganda and disinformation” is just slightly too stunning to be laughable. Without exception, the United States engages in every one of these practices and violates every single one of these bullet pointed virtues of a Clean Internet. Where do we get off?

The post-9/11 NSA phone surveillance program, through which major telecom carriers like AT&T and Verizon cooperated with the government to provide sensitive data for hundreds of millions of calls and texts, was only shut down last year (and only reportedly shut down at that). Though critics of the China-originated social network TikTok are quick to point to Chinese tech firms’ data-sharing obligations to their government, we don’t need to look to the other side of the world to find such opaque arrangements. As the New York Times noted when the NSA program was terminated, “Starting in 2006, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court began issuing secret orders requiring the companies to participate, based on a novel interpretation of Section 215 of the Patriot Act, which said the F.B.I. may obtain business records ‘relevant’ to a terrorism investigation.” Long-running fears that pre-tampered communications equipment manufactured by China’s Huawei could breach American networks start to feel a bit morally hollow when you recall the NSA investigated these fears by breaching Huawei itself while simultaneously exporting pre-tampered network equipment from Cisco, a U.S. firm. A psychologist might describe U.S. concerns in this area as “projection.”

We’re on similarly weak footing when it comes to browbeating other countries about privacy-violating apps, an industry the U.S. has proudly pioneered. It is the rare American citizen whose daily movements, habits, tastes, and desires aren’t surveilled around the clock by a constellation of for-profit firms whose names they will never know and whose interests they will rarely share. At a recent congressional hearing on the monopolistic practices of American tech companies at which he stated his company stood for “American values,” Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg was asked about a virtual private network the company deployed to smartphones to spy on children and adults in exchange for bribes–or, as Facebook put it, for “market research.” Zuckerberg denied that he had ever heard of this incident even as he told Congress, under oath, that the company doesn’t use cookies to track private information (it does). Pompeo’s denunciation of the “PRC surveillance state” sounds like little more than surveillance state protectionism.

Google’s Android phones come pre-installed with a long list of always-on, always-listening, always-tracking features that quietly surveil customers’ smartphone habits and locations: data increasingly handed over to police, and, as always, leveraged for targeted advertising by a mind-boggling range of companies.

There’s very little here that could be considered “clean,” unless it’s the Awesome Cleaning Power of Dove Soap your phone is now recommending to you because it’s persistently tracked by Facebook, Google, and countless marketers. Skype, one of the world’s most popular and trusted pieces of software, was infamously sabotaged by its American owner in order to let the NSA effectively spy on conversations it carried. The rest of the world is surely raring to feel this kind of Clean.

Pompeo calls for a “Clean Cloud” that can’t be “accessible to our foreign adversaries.” It would be interesting to hear Pompeo’s pitch for why other countries should instead turn to, say, Amazon’s AWS cloud service, used by the CIA and NSA. The U.S. government should think very carefully about whether it wants to tell the world that a company’s intelligence community adjacency and long-running collaboration should be a red flag before doing business.

Pompeo’s determination to “ensure the undersea cables connecting our country to the global internet are not subverted for intelligence gathering by the PRC at hyper scale” is maybe his most morally bankrupt initiative. “We will also work with foreign partners to ensure that undersea cables around the world aren’t similarly subject to compromise,” he promises, not noting that it’s precisely ourselves and these “foreign partners” in the Five Eyes spying alliance that have for decades made sure that undersea cables are subject to compromise. NSA programs with names like FAIRVIEW, STORMBREW, and OAKSTAR revealed by Snowden show just how invested the U.S. is in spying on the internet’s physical fiber optic backbone in absolute secrecy to carry out the country’s national security agenda.

The American “Do as we say, not as we do” approach to the internet has always been the case, but reached an apex with the debate over “banning” TikTok, a Chinese-owned video sharing app counted among the most widely used pieces of software in history. I’ve found it to be an worthwhile exercise to take a random piece of the national security centrist consensus against TikTok, which framed the teen-beloved app as the data security equivalent of a comical smoking bomb from a Batman cartoon, and swap out “TikTok” for, say, Facebook. The think tank arguments for a national ban against dishonest tech companies that harvest as much data as possible and backchannel with spy agencies and police hold up pretty well no matter which company is slotted into the national security mad libs. There’s no reason to believe TikTok vacuums up more data than Facebook or any other app, whose owners, in the absence of any meaningful regulation, can do whatever they please with that information in perpetuity.

To consider Mark Zuckerberg, Sundar Pichai, and the rest of the Silicon brass as meaningful foils to Chinese secrecy, sabotage, and subterfuge, as some bulwark of democratic ideals, is an insult to anyone paying attention. The nightmare of Chinese techno-authoritarianism does not in any way absolve the Surveillance State Lite we’re erecting at home. However easy it may be for the Chinese government to access data within its own borders and no matter how nefarious their intent, the average American ought to wonder whether they face a greater imminent threat from that country’s authorities or the U.S.-based surveillance marketing companies that actively try to preempt and subvert their personal autonomy every minute of every day, or the brutalizing police agencies that happily piggyback on these data troves.

We’ve known since NSA contractor Edward Snowden helped expose various surveillance programs seven years ago that information from Silicon Valley heavies like Google, Facebook, and Apple was routinely and systematically provided to the NSA, subject in many cases only to the oversight and transparency of secret courts, secret proceedings, and secret findings. It will take a greater mind than Pompeo’s to argue why our opaque public-private national security data funnel is meaningfully democratic and genuinely open. Less docile firms can find themselves the recipient of a federal “National Security Letter,” which not only mandates that they turn over the requested data, but forbids them from even mentioning that they’ve been asked under penalty of imprisonment. If we’re condemning the general practice of duplicity in the name of national security, rapaciousness in the name of intelligence, and constant violation of civil liberties and personal privacy online, it’s odd to let the Stanford graduates who run Silicon Valley so completely off the hook.

There’s no need to attempt to draw a moral equivalence between China and the United States; the network of totalitarian, ubiquitous surveillance and repressive policing erected in Chinese cities can only make Palo Alto executives and police union bosses green with envy for now, though we can’t knock them for not trying. The horrors of Uyghur concentration camps in Xinjiang–of their brutalization, dehumanization, and worse–are without equal in this country. China’s domestic human rights abuses and civil liberties disintegrations are orders of magnitude greater than our own. But just because someone else is far worse doesn’t mean that we are good, or clean, worth emulating, or worth listening to at all. The systemic surveillance and harassment of Muslim communities is either wrong, or it’s not. The internment of ethnic groups in fenced-in pits and cages is either wrong, or it’s not. Persistent corporate surveillance conducted by firms with close ties to the military and spy agencies is either a problem, or it’s not. Tapping undersea fiber optic cables, backdooring network equipment, and turning smartphones into tracking devices is either something no one should do, or it’s not. Marketing apps to young people and then hoovering up their data to be subject to facial recognition or machine learning or who knows what else should either offend us or not, regardless of whether perpetuated by Zuckerberg or TikTok boss Zhang Yiming; Silicon Valley’s captains of industry long ago forfeited moral superiority over their Chinese counterparts. At the very least, I’m not aware of Yiming ever telling his friends that people were “dumb fucks” for trusting him with their data.

The argument that the United States can and should be able to get away with all of this because of our democratic values, or commitment to human rights and human dignity, our fair judiciary, our principled executive, and our diligent legislative branch will convince some people itching for a fight with China — those people for whom there are simply Good Guys (us) and Bad Guys (them) — but to the rest of us should leave a sour taste, particularly given the current administration. Trumpeting America’s superior “rule of law” against Chinese-style data practices is less reassuring while unidentified federal commandos are stuffing people into the back of vans and the Department of Justice is commanded by an open crony of the White House. You’ll hear and read much in the coming weeks about how Pompeo’s “Clean Network” program could mean the beginning of two fractured internets: one Red Chinese, and one Proudly American. It will be crucial to bear in mind that while China’s vision of the techno-future is revolting, dangerous, and worth fighting against however possible, the American Net is anything but clean.

(Sam Biddle is a reporter focusing on malfeasance and misused power in technology. Article courtesy: The Intercept. The Intercept is an award-winning US-based news organization dedicated to holding the powerful accountable through fearless, adversarial journalism.)