The Dialectics of Constituted and Communal Power: A Conversation with Ángel Prado

Chris Gilbert and Cira Pascual Marquina

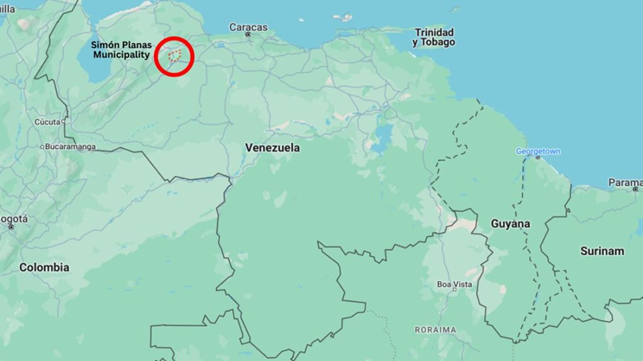

[El Maizal Commune lies at the gateway to Venezuela’s Llanos region, between the states of Lara and Portuguesa. It is one of the most consolidated communes in Venezuela with some 3500 families living in its territory; vast expanses of land dedicated to corn and cattle; and a range of productive projects.

Ángel Prado is the commune’s main spokesperson. Two years ago he won a difficult battle to become mayor of Simón Planas, which is the municipality comprising most of El Maizal along with 11 other communes. In this interview, Prado discusses his efforts in conjugating constituted power with the longstanding project of developing communal power.]

El Maizal Commune is in the Simón Planas Municipality. (Google Maps)

❈ ❈ ❈

Venezuela Analysis: Some of our readers are surely familiar with El Maizal, but could you present an overview of the commune?

Ángel Prado: El Maizal is a sum of experiences, practices, victories, and defeats. However, it is first and foremost a program and project bequeathed to us by Chávez, a program that shapes who we are and how we organize.

El Maizal embodies the communal way of life, which is based on seeking innovative methods and political approaches to create a better world. Of course, this new way of living is not defined by the logic of capital, but by putting what there is in common and ensuring dignity for all.

El Maizal brings together 27 communal councils and 2335 hectares of communal land. Beyond that, it has been able to link its work to that of the other communes in Simón Planas and with those in the Communard Union, which is a national organization made up of more than 50 communes. This is all very important because, as Chávez once said, communes can’t remain isolated; if they do, they will be devoured by the hegemonic system, which is capitalist.

I think that El Maizal contributes significantly to our society and our class, because it adheres to Chávez’s roadmap. That’s why our commune – like many others – serves as a beacon, an example that inspires popular organizations around the country and even around the world.

VA: Communes are more than just political entities; they represent an emerging economic model based on new social relations. Could you elaborate on this?

AP: The battle against capitalism takes place on a large scale; it’s about dismantling the existing norms, especially concerning property. That’s why the collective ownership of property, the collectivization of work, and, of course, the communal distribution of surplus are so important.

Our end goal is to establish a culture of communal property countering the individualism promoted by capitalism. We aim to bring people together, organize within and for the community, and protect our means of production, all the while advancing toward industrialization and direct distribution. Ultimately, we aim to control the entire production cycle.

Currently, because we are primary producers, the surplus of our communal production is often captured by the capitalist market. This is a serious problem, which underscores the importance of communal industrialization.

What I am saying is not just true of El Maizal Commune: all communes need to industrialize. Failing to do so means having a survival economy on the periphery of the existing capitalist system.

VA: After the fall of the Soviet Union, much of the global left turned its back on state power. Arguably, Chávez played a crucial role in repositioning the concept of “taking power” into the discourse of the left.

In Simón Planas, the communal movement sought a foothold in a space of constituted institutional power: the Mayor’s Office. It did so by supporting your successful campaign to become mayor. Why was it important to control that institution?

AP: As Chavistas and communards, we aim to control existing resources and put them at the service of the people. In our case, this means taking control of the means of production and of the public institutions in our municipality.

El Maizal has a long history of communalizing vacant land and means of production, but more recently we succeeded in taking control of the Mayor’s Office by participating in the elections. Like Chávez, we don’t shy away from such contests.

Depending on who controls it, a local government can help or hinder progress toward communal goals and we work hard to do the former. Following Chávez, we believe in actively disputing power: seizing and placing it at the service of the people. Without Chávez’s ascent to political power, the commune wouldn’t have gained traction. His leadership was key to promoting the socialist project and rekindling discussions about the utopia we pursue.

Of course, it’s important that one not be devoured by power; instead, it should serve the people. In our country, when wielded in a revolutionary manner, state power can become a catalyst for advancing the commune.

VA: Chávez repeatedly pointed out that Venezuela still has an essentially bourgeois state. Your objective as mayor is not to strengthen the bourgeois state but to create conditions for its dissolution. What are the dangers and opportunities, for you as a communard, in engaging in state-level politics?

AP: Even when Chávez was alive, there was a campaign within the state to discredit the communal model, portraying it as outdated, unsuccessful, or inefficient. These notions persist. That is why we view our participation in the local government as an opportunity to show that communards can adeptly manage institutions.

Initially, we faced many challenges due to widespread skepticism. However, we have demonstrated that with political determination, adherence to principles, and a clear objective we can efficiently administer the apparatus of municipal government, placing it at the service of the people. We see the it as a tool, but the true catalyst for social transformation is the communal movement.

Nonetheless, there are potential pitfalls and dangers. If we were to interpret the Mayor’s Office as the focal point of politics, we would be failing as revolutionaries and Chavistas, since we would be abandoning what should be the core of our political and economic life: the commune.

VA: Your administration as mayor of Simón Planas has proven highly effective. Municipal institutions have solved numerous problems with infrastructure, healthcare, and education. While these achievements are commendable, how do they contribute to the strategic goal of communal socialism?

AP: From the Mayor’s Office, we have actively promoted debates, referendums, and collective decision-making processes. In other words, consultation is integral to our form of governance, which should be more and more communal every day.

For example, a year ago, we organized a referendum on participatory budgeting. The primary goal was to take down obsolete city ordinances that had been in place for over two decades, hindering our ability to budget, legislate, and govern collaboratively with the people. The referendum had several specific objectives: we wanted to reallocate funds once controlled by high-ranking officials to public works and we wanted to open crucial decision-making processes to the pueblo.

The referendum was a success. There was high participation and that paved the way for a new model of governance in which resources, information, and decision-making are no longer in the hands of a select few. Now the community participates in the political and economic direction of Simón Planas, thus strengthening communal organization.

VA: Some of the comrades we have talked to here say that the “communal government” should eventually replace the Mayor’s Office. But what exactly is a “communal government” in that context?

AP: Essentially, a communal government is the government by the people and for the people. It materializes when the community collectively decides what must be done and actively participates in its planning and execution. A communal government operates with autonomy, sovereignty, and the freedom to make decisions without institutional constraints.

Inspired by Chávez’s vision, our objective is to dissolve old institutions, such as the municipal government, and replace them with self-governed spaces fully committed to the communalization of society.

(Cira Pascual Marquina is Political Science professor at the Universidad Bolivariana de Venezuela in Caracas. Chris Gilbert teaches Marxist political economy at the Universidad Bolivariana de Venezuela. Courtesy: Venezuela Analysis, an independent website produced by individuals who are dedicated to disseminating news and analysis about the current political situation in Venezuela.)