“We forget that nature itself is one vast miracle transcending the reality of night and nothingness,” the anthropologist and philosopher of science Loren Eiseley wrote in his poetic meditation on life in 1960. “We forget that each one of us in his personal life repeats that miracle.”

The history of our species is the history of forgetting. Our deepest existential longing is the longing for remembering this cosmic belonging, and the work of creativity is the work of reminding us. We may give the tendrils of our creative longing different names — poetry or physics, music or mathematics, astronomy or art — but they all give us one thing: an antidote to forgetting, so that we may live, even for a little while, wonder-smitten by reality.

In the same era, the science-inspired poet Robinson Jeffers (January 10, 1887–January 20, 1962) took up this reckoning in the final years of his life in an immense and ravishing poem that became the title of his collection The Beginning and the End, published the year after his death.

Jeffers was not only an exquisite literary artist, but a visionary who bent his sight and insight far past the horizon of his time — he wrote about climate change long before it was even a tremor of a worry in the common mind, even though he died months before Rachel Carson published her epoch-making Silent Spring, which awakened the human mind from its ecological somnolence and seeded the environmental movement. But although he is celebrated as one of the great environmental poets, he was as enchanted by the wonders of nature on Earth as beyond it, for he understood better than any artist since Whitman that these are parts of a single and awesome reality, and we are part of it too — not as spectators, not as explorers, but as living stardust.

Born into an era when the atom was still an exotic notion for the average person and molecules a mystifying abstraction, Jeffers drew richly on the fundamental realities of nature — in no small part because his brother, Hamilton Jeffers, was one of the era’s most esteemed astronomers, having gotten his start at the Lick Observatory — the world’s first real mountaintop observatory, where the first new moon of Jupiter since the Galilean four had been discovered months before Hamilton was born.

Jeffers wrote about black holes and the Big Bang, about amino acids and novae, about the indivisibility of it all — nowhere more beautifully than in “The Beginning and the End.”

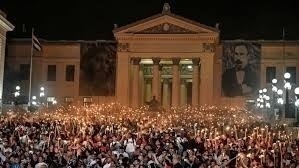

Sixty springs after he returned his borrowed stardust to the universe, his eternal poem came alive in a redwood-nested amphitheater down the mountain from the Lick Observatory, as the opening poem of the fifth annual Universe in Verse, read by my darling astronomer friend Natalie Batalha, who led the epoch-making discovery of more than 4,000 potential cradles for life by NASA’s Kepler mission and now continues her work on the search for life beyond our solar system with the astrobiology program at UC Santa Cruz.

As usual, Natalie prefaced her reading with a poignant reflection that is itself nothing less than a prose poem about the nature of life and its responsibility to nature — that is, to itself:

We are Earth. We are the planet. We are the biosphere. We are not distinct from nature.

Yet, at the same time, we are, as life — as living things: ourselves, the redwoods, the birds overhead — we are the pinnacle of complexity in the universe, from the Big Bang until now. It took 13.7 billion years for the atoms to come together to form this portal of self-awareness that is you.

[…]

Given this ephemeral existence that we have, of self-awareness, what are you going to do with your moment? What are we, as a species, going to do with our moment?

Excerpts from “The Beginning And The End”

Robinson Jeffers

The unformed volcanic earth, a female thing,

Furiously following with the other planets

Their lord the sun: her body is molten metal pressed rigid

By its own mass; her beautiful skin, basalt and granite and the lighter elements,

Swam to the top. She was like a mare in her heat eyeing the stallion,

Screaming for life in the womb; her atmosphere

Was the breath of her passion: not the blithe air

Men breathe and live, but marsh-gas, ammonia, sulphured hydrogen,

Such poison as our remembering bodies return to

When they die and decay and the end of life

Meets its beginning. The sun heard her and stirred

Her thick air with fierce lightnings and flagellations

Of germinal power, building impossible molecules, amino-acids

And flashy unstable proteins: thence life was born,

Its nitrogen from ammonia, carbon from methane,

Water from the cloud and salts from the young seas,

It dribbled down into the primal ocean like a babe’s urine

Soaking the cloth: heavily built protein molecules

Chemically growing, bursting apart as the tensions

In the inordinate molecule become unbearable —

That is to say, growing and reproducing themselves, a virus

On the warm ocean.

Time and the world changed,

The proteins were no longer created, the ammoniac atmosphere

And the great storms no more. This virus now

Must labor to maintain itself. It clung together

Into bundles of life, which we call cells,

With microscopic walls enclosing themselves

Against the world. But why would life maintain itself,

Being nothing but a dirty scum on the sea

Dropped from foul air? Could it perhaps perceive

Glories to come? Could it foresee that cellular life

Would make the mountain forest and the eagle dawning,

Monstrously beautiful, wings, eyes and claws, dawning

Over the rock-ridge? And the passionate human intelligence

Straining its limits, striving to understand itself and the universe to the last galaxy.

[…]

What is this thing called life? — But I believe

That the earth and stars too, and the whole glittering universe, and rocks on the mountain have life,

Only we do not call it so — I speak of the life

That oxydizes fats and proteins and carbo-

Hydrates to live on, and from that chemical energy

Makes pleasure and pain, wonder, love, adoration, hatred and terror: how do these thing grow

From a chemical reaction?

I think they were here already. I think the rocks

And the earth and the other planets, and the stars and galaxies

Have their various consciousness, all things are conscious;

But the nerves of an animal, the nerves and brain

Bring it to focus

[…]

The human soul.

The mind of man…

Slowly, perhaps, man may grow into it —

Do you think so? This villainous king of beasts, this deformed ape? — He has mind

And imagination, he might go far

And end in honor. The hawks are more heroic but man has a steeper mind,

Huge pits of darkness, high peaks of light,

You may calculate a comet’s orbit or the dive of a hawk, not a man’s mind.

(Maria Popova is a Bulgarian-born, American-based essayist, book author, poet, and cultural critic. Her writings are featured on her blog, The Marginalian. Courtesy: The Marginalian.)