Harsh Mander

Something has shifted, something has changed, something has broken in India, after the momentous ruling on the disputed land in Ayodhya.

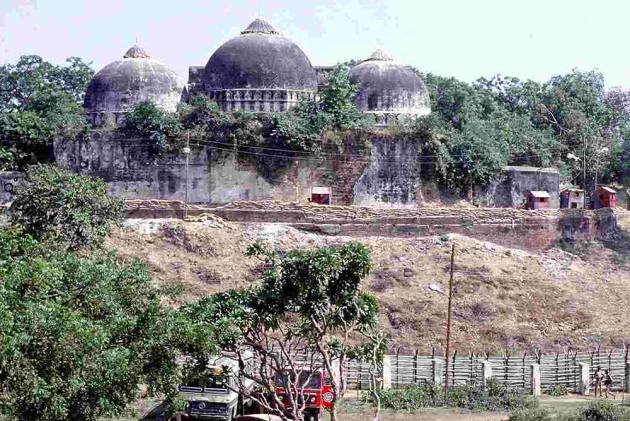

The learned judges of the Supreme Court of India could not have been unmindful during their marathon hearings in the case that this was not simply a title dispute over a tiny piece of land about the size of two football fields in a dusty small town in Uttar Pradesh.

It was not even a contest between a medieval mosque, now razed, and a grand temple, still imagined. It was a dispute about what kind of country this is and will be in the future, to whom does it belong, and on what terms must people of different identities and beliefs live together in this vast and teeming land.

There was one idea of and for India – one for which Mahatma Gandhi willingly laid down his life. This was of an India which would belong equally in every respect to people of every faith and identity. The idea that India’s Muslim citizens could confidently and legitimately lay the same and equal claim to the land of their birth and their choice as could India’s Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Christians and Parsis. The assurance that there would be no hierarchy of faiths, beliefs and sentiments, no obligation for one set of people to be willing to forego their claims in deference to the claims of people of the powerful and majority faith.

Pitted resolutely against this idea was another imagination of and for India – that this was a nation which belonged to its (upper-caste) Hindu people; that it welcomed people of Sikh, Jain and Buddhist identities because their religions also rose from Indian soil; but that Islam and Christianity were ‘foreign’ faiths, and their adherents would be ‘allowed’ by the Hindu majority to live in India but only on the condition that they subordinated their faith to the sentiments and beliefs of the majority faith.

From the opening paragraphs of the judgment, it is apparent that the judges of the Supreme Court regarded this case to be in the nature of a dispute between the Hindu and Muslim people of India. This it was not. It was a dispute between self-styled organisations which claim to represent the sentiments and interests of Hindus and Muslims, but have no explicit mandate to do so, nor empirical evidence that they enjoy the wide support of people of these faiths.

Even so, in the opening paragraph of the judgment, the judges speak of the disputed site as being of great significance to Hindus and Muslims. It often substitutes the names of the litigating individuals and organisations with ‘the Hindus’ or ‘the Muslims’. This is worrying and misleading. The Vishwa Hindu Parishad, a militant Hindutva outfit and close affiliate of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, does not represent Hindus at large, any more than the Uttar Pradesh Sunni Central Board of Waqf represents India’s Muslims.

The judgment looks closely at questions of both history and faith, even though in the end it caveats that its rulings are based on neither of these. The judgment concludes that at the site on which the mosque stood lay a religious structure which was not Islamic, dating back to the 12th century, and that the preponderance of evidence suggests that this was a Hindu temple. It, however, adds that there is no evidence that the temple was actually demolished to build the mosque.

The archaeological evidence which the court chose to cite is not uncontested or conclusive. But even more pertinently, the question of whether there was indeed a Hindu temple at the site at which the mosque was built was irrelevant since there are no sound legal and constitutional grounds to try to correct – in the 21st century – the possible wrongs of history, as the entire movement for building the Ram temple at the site of the mosque led by L.K. Advani sought to do? And if there are grounds, who will decide where this will end? Will these ‘correctives’ apply to other disputed places of worship? And further, how far in history should we go? Why stop at 500 years of history? Why not a 1000, or 1500, or 2000 years, or longer? There are historical records that establish that large parts of India were Buddhist until the 9th century, and that Buddhism was crushed and almost wiped out of India by Brahmanical Hinduism, often with brutal force. Many temples were built by demolishing Buddhist stupas. So should we now advocate the restoration of Buddhist places of worship at sites where Hindu temples stand? And indeed, what about the sites of worship of India’s many tribal communities, which were forced to give way through millennia to Hindu places of worship? Will the learned judges advise us how far in history we should go, and why we should select some histories and not others to rectify? Even more importantly, will they clarify to us what in our constitution and law justifies these judicial choices?

One of the learned judges – who authored an “addendum” to the judgment – is of the opinion that the ‘faith and belief’ of Hindus is that Lord Ram was born at the precise site of the mosque, and therefore he supports the decision of his brother judges to hand over the site where the mosque was razed for the construction of a temple to Lord Ram. It is both curious and disturbing how the alleged faith and belief of a community can be relevant in any way while resolving a property dispute. Moreover, while it is entirely true that Hindus believe that Lord Ram was born in Ayodhya, there is a diversity of beliefs if the Ayodhya of his birth is in fact present-day Ayodhya. And even within present-day Ayodhya, there are multiple sites which residents claim to be where Lord Ram was born.

In the opening paragraph of the judgment, the court states that the ‘Hindu community’ believes that the disputed site was ‘the birthplace of Lord Ram, the incarnation of Lord Vishnu’. This is simply not true. Some Hindus believe that Ram was born at that precise location, and others do not. On what grounds does the court privilege one ‘faith and belief’ that Ram was born under the domes of the demolished mosque over the ‘faith and belief’ of innumerable other Hindus that Ram was born elsewhere?

There is one other issue of enormous moral and legal salience which the judgment completely sidesteps. This is the consequence of three criminal acts which resulted in the de facto conversion of the mosque into a temple. The first criminal act which interrupted worship in the mosque was the surreptitious and illegal introduction of the Ram idol in the mosque in 1949. The second was the celebratory demolition of the mosque in 1992 by a fevered mob, cheered by leaders like Lal Krishna Advani. The third was the violation of court orders prohibiting any alteration of the status quo of the site, by building a makeshift Ram Temple where the demolished mosque stood, during the 36 hours which followed the demolition of the mosque.

While the judgment recognises at least two of these crimes, what it does in effect is to reward those who broke the law, defied the orders of the Supreme Court, and above all dishonoured the guarantees of India’s constitution and the central article of faith of India’s struggle for freedom – of the equality of all religions. This order would probably have been inconceivable if the mosque still stood at the disputed site. The court does acknowledge in its judgment this wanton debasement of the law, yet rewards the party responsible for this, for the multiple assaults on the law, the constitution and the Supreme Court. It seems unmindful that these crimes took the toll of hundreds of innocent lives in communal violence that rocked the country from 1989 to early 1993, and that its unhealed wounds continue to tear apart the country decades later. It believes the award of five acres of land for the building of a mosque is “restitution” enough, overlooking the fact that finding land to build a mosque or temple was never the problem in this protracted dispute. It was whether those who razed the mosque should be punished or rewarded for their illegal act by being allowed to erect a temple at the very site of their crime.

The judgment is, in the end, an intensely worrying signpost of where our country is headed. The direction has been unmistakable for some years now. However, we had still hoped that India’s highest court would steady our ship in the frightening darkness and perils of this enveloping storm; that it would rise to fight the winds and return us to the course of peace and equal citizenship that was imagined in our freedom struggle and pledged in our constitution. But that was not to be. History will long remember this moment, for what it was, and for what it could have been.

(Harsh Mander is a social worker and writer.)