(Published on the occasion of Ritwik Ghatak’s 95th birth anniversary on November 4.)

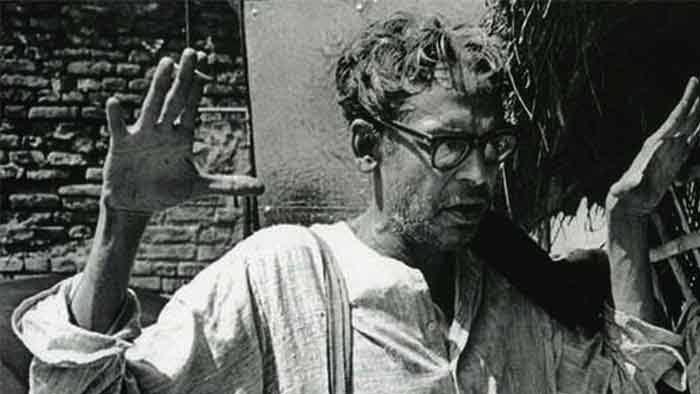

Ritwik Ghatak was born in 1925 in Dhaka and died in 1976 in Calcutta. Almost his entire adult life was spent working for the stage or the screen in some capacity or the other. It is perhaps inevitable that success – as most of us understand it – should have refused to come to him, considering the kind of man he was, the kind of life he led, or the quality of the ideas he preached as an intellectual and artist. Ghatak lived and died as the Ultimate Marginal Man – educated, cultured, intellectually sophisticated, and constantly wrestling to defeat the premises, fiats and expectations of conventional middle-class bhadralok society. When he died, there died with him an epic vision that caused him to take on extraordinary narrative, visual, aesthetic and technical challenges to create pioneering and lasting works.

It is said that Ghatak died of a personal inability to accept the traumatic fact of Partition; of frustrated dreams at being unable to reach his films to the people; and an excessive intake of alcohol. It speaks volumes about the illiteracy of the Bengali intelligentsia that whenever discussing Ghatak, they should take inordinate interest in the alcohol factor in the director’s life, frequently to the exclusion of more important things. The bold, authentic, and at times the almost earthquaking outlines of the artist’s form are lost in the fabricated fumes of the heady brew. It is about time idle chatter bordering on the malicious and trying to pass for informed criticism, is exposed for what it actually is.

Born and raised in what was once relatively undisturbed tribal country but which has since long been usurped by non-tribal carpetbaggers, this writer is understandably drawn to the concern and compassion for tribals that one sees in Ghatak’s films, both drama and documentary. Tribals are fourth- and fifth-class citizens in their own land; living on the fringes of a society where practically everyone appears to be doing well except they. They are truly strangers in their own country. Even as UN agencies hold seminars on the status of indigenous peoples or, nearer home, Ranchi, the capital of the supposedly tribal State of Jharkhand, is the venue almost every day of political meetings discussing the conditions in which tribals live, their woes show no sign of decreasing. As it actually stands, their daily problems and perennial tragedies are irretrievably lost in the cacophony of make-believe and well-modulated rhetoric.

Mainstream artists are mainstream artists precisely because they are given to pretending – and unfortunately, often getting away with it – that those who have been rendered surplus to the standard force, to use a common piece of industrial jargon, by the devious dynamics of mainstream politics, simply do not exist. Their choice and treatment of subjects are so designed as to leave their readers or viewers none the wiser about the origins and present status of those bronzed people who were once at the centre of things but who, over many decades, have been relegated to the margins. Ghatak is one film artist who never ceased to focus on the voiceless, the uprooted, the homeless and the marginalized with all the resources at his command. What the Partition of Bengal and the resultant loss of a place of one’s own did to him was that it gave him a greater role than any he gave to the male or female protagonists in his films – it gave him the right to speak in that memorable, unmistakable voice of his for every refugee on the face of the earth. To him, the tribal of Singhbhum, Ranchi or Purulia was as much a refugee, cheated of his patrimony, his inheritance of land and belongings, of his ideas of war, worship, love and death, as those who had to leave their dear little villages along the Padma, the Meghna and the Jamuna and start life anew in Calcutta and innumerable other Dhakas, Faridpurs, Borishals or Chittagongs in Assam, Bihar, Orissa, Delhi, Maharashtra and elsewhere.

Some writers, it is true, have addressed themselves to the fallow and fractured lives of the Adivasis, the so-called Harijans and other similarly outraged Indians. In this connection, the names of Mahasweta Devi or Namdeo Dhasal readily come to mind. Although these writers have expressed themselves with honesty and feeling on the inhuman conditions in which tribals or Dalits are compelled to live and die, they have not been as effective as one would have wanted them to be. Given the times in which we live, the written word is more often than not destined to remain trapped and unexplored between the hard or soft covers of a book. The written word does not seem to have the power of the moving image.

***

Indian filmmakers could have done a lot to awaken society’s sleeping conscience to the tribal experience, if only they had chosen to. Ghatak was an exception; a pioneer here, as in so many other areas of conviction and creativity. He made many worthwhile attempts to understand the Adivasis of Bihar and Bengal in particular, as he encountered them in all their glory and all their abjectness. Apart from the more than one documentary he made on the Adivasis, several of his fictional features were shot in tribal country. Together, these give intimate glimpses of the aboriginal lifestyle in its varied expressions. Here, perhaps it would be correct to say that although he was not trained in anthropology or psychology, Ghatak has in his own way done more than many formal practitioners of these disciplines to help us understand varied facets of the Adivasi presence – their collective psyche, their rootedness in Nature and in the elements, or their sense of abandon to cover up their material deprivation, which has often led to an ineffable spiritual desolation. If serious efforts are still made to preserve Ghatak’s films with the loyal and loving care they deserve, there may come a day when these would be of immense archival value in terms of the fast disappearing tribal way of life. The extended dance-and-drink sequence in Ajantrik, for instance, is not just mesmerizing cinema capable of transporting the liberated and receptive middle-class viewer to a strange and difficult nether world, but an authentic record of fun and games, albeit laced with sadness, that these primitive people can engage themselves in almost as a compensation for the other things of life that they have been robbed of by waves of guns and governments.

Ghatak’s flights of creative fancy – absurd and pure – merged with the tribal genius for divining life in terms of innocent pleasures that the outsider who wishes to remain an outsider will sadly never know. True, Ghatak, too, was an outsider; yet, helped by a combination of love, respect and intellectual vibrancy, he was not. He has tellingly mentioned in connection with Ajantrik, the impossible love story between a poor man of bhadralok stock and an old machine of high pedigree – a dilapidated 1920 Chevrolet – and arguably his finest film in close competition with Titas Ekti Nadir Naam: “The tribals are the people who own the land where the story is laid. Without them the landscape would lose its charm and meaning. I cannot marshal my camera on any spot without integrating them into my composition. Also, it is a silly story. Only silly people can identify themselves with a man who believes that a godforsaken car has life. Silly people like children, simple folks like peasants, animists like tribals.”

For both the viewer and the reader, Ghatak is a great stimulation. An impassioned protestor against the rape of virgin tribal land by big industry, entrepreneurs, contractors and other fly-by-night operators, the philosopher in him however, makes him sadly accept the inevitability of change. Agreeing to the proposition that man and machine must co-exist, is not easy for him, but there is no other choice. Doubtless a difficult marriage this, but one that has to be consummated with a prayer that it would not turn out to be an unrelieved disaster in the end.

It is a pity that Ghatak failed to complete his documentary on the legendary tribal painter-sculptor of Shantiniketan, Ramkinkar Bej. If he had completed it, the film would have not only upheld the figure of the homegrown, homespun artist as a creative rebel carrying universal meanings, but also allowed audiences throughout the land a grand view of a people rich in gifts of the spirit inconceivable to modern, technological man. Again, this would have been a rare document of a people in tragic transition; a people weaned away from Nature by the seductive embrace of electronic goods and technological gadgets; precariously poised between holding on to the past and adjusting to the present which promises much more than it actually delivers.

Temperamentally and instinctively, Ghatak was suited to understanding and appreciating the tribal persona. Middle-class, bhadralok, city-bred, Tagore-lover, cultured and enlightened in a modern 20th-century way, he was however, both inventive and iconoclastic enough to de-class himself emotionally without letting go of his enormous intellectual baggage. In the process, he ran into contradictions, but he never allowed these to prevent him from discovering in the Adivasis a many-splendoured subject worthy of stark, at times subtle, but never seductive depiction. He could not visualize even in his wildest hallucinations going the way of a hundred other films in different Indian languages where the tribal had been reduced to a cardboard cut-out in keeping with borrowed ideas about him by the average middle-class city-dweller. It was this soil sensibility in him that attracted Ghatak to the earthy genius of Ramkinkar, not to the sophisticated genius of Benode Behari Mukhopadhyay, immortalized by Satyajit Ray in the documentary, The Inner Eye.

Here, the words of the late Shantiniketan artist and art critic Jaya Appasamy on Ramkinkar come into sharp focus, for they are equally applicable to Ghatak, the celluloid troubadour of the animist spirit born in the mud, grown in the rain, priding itself in its windy perfection, and one day settling in the dust to be reborn in the mud. Appasamy wrote: “Anyone who wishes to be an artist has to make a difficult choice. Ramkinkar has shown by his life what an artist’s life is. It is by no means soft, it is a life of striving, its satisfaction is in the struggle, not in what has been done. Ramkinkar pursued a lonely path and was often considered a rebel, which all artists are when they teach us to see anew. If being a rebel was the same as being an artist, Ramkinkar was a rebel par excellence, a man who by his life has left us an ideal.”

By the same definition, Ghatak, too, was a rebel par excellence who struggled all through his brief and chequered life to create films of lasting truth and beauty. Employing a corrosive aesthetics of disintegration in a style that mixed neo-realism with bursts of unforgettable poetic realism, he gave to avant garde Bengali cinema documents of horrible truth and ennobling beauty.

In Jukti Tokko Aar Goppo, which may be said to be his summing-up film, Ghatak devoted considerable space to the rich folk art and marginal existence of the chhou maker, Panchanan Ustad, whose striking robustness, child-like innocence and great humanity remind the viewer of Ramkinkar. Panchanan Ustad’s personal lifestyle and his grassroots perceptions about life, art and society are established by the help of cinematic strokes at once bold and bewildering. Ghatak keeps moving freely between the individual and the collective experience; valuable insights into the close community life of Birbhum tribals are gained with the same fluidity and spontaneity as the lonely, poverty-stricken life of the aging folk artist.

The detailed chhou sequence in the film where the camera is as energetic a performer as the masked men and children playing familiar characters out of the epics, stands out unforgettably in this largely autobiographical road movie. The film, characterized by narcissistic excesses, may seem overwrought in parts, but what is more relevant here is that the masked dance complete with maces and spears, pipes and drums, exaggerated movements and stylized poses, and finally intense audience participation, amounts to an in-depth probing of the experience of an unjustly deprived people who are, paradoxically, rich enough in invisible resources to keep their life flow and artistic traditions alive.

Many of Ghatak’s short stories, which are being discovered and assessed anew, are also set in tribal territory. Since he thought it necessary to approach the tribals with a genuine appreciation of their trials and occasional fulfilments, Ghatak was able to gain many a rare insight into their individual mind and collective unconscious. Towards the close of his short life during which he worked at a feverish pace to realize what we now recognize as an extraordinary will and vision at work, tribals and other wretched of the earth came to occupy an increasingly important place in his art. True respect combined with an inexhaustible eagerness to know them in an intimate sort of way may be said to have been one of the hallmarks of this great artist’s small but scintillating oeuvre.

***

Ritwik Ghatak’s penultimate film, Titas Ekti Nadir Naam, was for the first time commercially released in Calcutta in the summer of 1991, almost two decades after its completion. Every show at Nandan, the West Bengal Film Centre, was solidly booked. The city’s newspapers and coffee houses treated it as a celebrated event; the return of the misunderstood, often maligned, genius to the consciousness of his people.

Made soon after the liberation of Bangladesh, this 150-minute epic, based on a kaleidoscopic novel by Advaita Malla Burman, was very much after Ghatak’s heart. The film depicted the joys and frustrations of the Malo fishing community of East Bengal, a lowly caste to which Malla Burman himself belonged. The film is nothing if not a classic on the economic extinction and spiritual decline of a once resplendent community whose strength lay in its unity and its acceptance of collective struggle as a way of life

Apart from the heightened quality of story-telling and its compelling visual energy, Titas provides memorable glimpses into the composite culture of rural East Bengal embracing the daily lives of the two religious communities, using the Malos as an exploratory springboard. And yet, the individual is always there at the centre of events – the individual as an observer, as a participant, and sometimes as a commentator. It is through the different roles the individual plays that the director’s profoundly humane philosophy is fleshed out.

There is desertion, decay and death in Titas; violence and destruction by both Man and Nature. But nothing can rob Ghatak of his optimism, his faith in the future, his belief that despite everything, the pervading darkness needs to be defeated and it is possible to do so. His vision was that of the exhausted traveller who had lost his effects and his energies on the way, and yet was not prepared to give up the journey because in that journey resided the reason for his existence. In the closing frames of Titas, Basanti, the leading protagonist, is shown dying, clawing at the dead river-bed of the once-effulgent Titas for a few drops of water. But even as she is dying, she sees a vision of a child running across a paddy field blowing on a reed horn. Ghatak wrote in regard to scenes of resurrected hope with which many of his films end but most notably Titas: “Civilization never dies, it may change but it is eternal. Where the paddy field is born on the dry river-bed of Titas, there begins another civilization.” Of such a one, the poor of spirit still say that he died of frustration.

Ghatak’s love of life is reflected in, among other things, his unique and peculiar brand of eroticism. A strange eroticism consisting largely of a play of words, most often among women, pervades Titas. A close ear for the Bengali language as spoken in East Bengal, particularly by rural folk, enhances one’s appreciation of this intimate aspect of Titas. At least two passages may be mentioned in this regard. The first is where Basanti, the child-widow now grown to mature womanhood and haunted by the spectre of emptiness, suggests playfully after listening to Rajar-jhi for a while, that perhaps the latter’s moods have something to do with the absence of a man in her life. Basanti’s playfulness is clearly a cover for the gnawing darkness that fills her own soul, occasionally spilling over into frightful encounters with those closest to her in blood and bones. Ghatak’s insights into female psychology and behaviour, especially in moments of crisis born of confrontation with society or with their unfulfilled inner selves, is especially noteworthy here.

Again, there is a passage towards the end of the film where Titas having dried up and the Malos economically destroyed, some of the women of the community are headed for the nearby town where the babus are reputed to pay well for a night of pleasure with them. At least one of the women, shown earlier in the film to be a possessor of pucca moral credentials, desperately proclaims that she would gladly do anything to please the babus if that is the only way to survive. Common to the two passages is Ghatak’s ability to invoke an erotic element in his story-telling with rare grace.

While Ghatak’s deliriously elemental signature is scrawled all over Titas, he is considerably helped in the building up and toning down and building up once again of pace, rhythm and atmosphere by assistants who bring to bear on their work the same love of Man and Nature or sadness over their decline and downfall as the director’s. Baby Islam’s black-and-white cinematography is an event in itself. It is obvious that he understands water and human beings living on its shimmering edges with the wisdom of a seer and the simplicity of a child. No praise is enough to describe what Islam accomplished in Titas, admittedly inspired to do what he did by Ghatak whose own sense of camera could often be simply out of this world. The nearest thing we have seen to this quality of work in Indian cinema in recent times is present in some of the Malayalam films of the last decade or two of the 20th century. However, perhaps it would not be out of context to point out that whereas ace Kerala cinematographers like Shaji, Venu or Sunny Joseph learnt the first lessons of their craft at the Film Institute in Pune, Islam began as a lowly apprentice in the Tollygunje film studios before Partition and gained his grasp of the camera gradually during a long stint in the industry, first in Calcutta and later in Dhaka. One more thing that should be said relates to the different standards people adopt when evaluating the work of our own artists and that of those belonging to the West. There is no doubt in many subcontinental minds that Titas’s breathtakingly composed frames would have surely brought Islam recognition of a far more enthusiastic kind at the international level had he belonged to a country with a more hoary cinematographic tradition.

Ritwik Ghatak’s was a life of intense involvement in whatever he did, be it acting, theatre direction, filmmaking, essay or short-story writing, or simply conversing. The involvement was born of a deeply-felt sense of partisanship. He would habitually say that every film, every filmmaker, every artist, every work of art was necessarily partisan. Either a work of art seeks to justify and preserve the status quo, or it aims at breaking down the old and rotten, and raise in its place a social order that is a little just, a little fair to the countless many languishing in the wilderness.

All his life, Ghatak wrestled with one and the same theme – the Partition of Bengal, which was first thought up more than a hundred years ago by the wily and wilful Curzon, Viceroy of India, but which came to be an irreversible fact of history in 1947. In a foreword to a collection of writings by Ghatak, Satyajit Ray observed : “Thematically, Ritwik’s lifelong obsession was the tragedy of Partition. He himself hailed from what was once East Bengal where he had deep roots. It is rarely that a director dwells so singlemindedly on the same theme. It only serves to underline the depth of his feeling for the subject.”

The deeply-wounded, angst-ridden director looked at the traumatic event from different angles, at different levels, but the reaction was always the same – a vehement rejection of the politics of division designed to secure narrow gains for some at the cost of millions. Even when he did a film not related to that tragic event, like for instance Ajantrik, it still carried the artist’s views on the plight of those rendered homeless by forces beyond their control. What unites Bimal who carries within himself vestiges of his once bhadralok self with the tribals in whose territory he plies his jalopy is their common absence of control over their respective destinies. Titas, too, is memorably cut from that consistent cloth of the besieged director’s sense of agony and ecstasy. The ecstasy is in remembering the innocence and purity that was, the agony is in having lost that valuable possession which will never be regained.

The distinguished Black American writer, Toni Morrison, had said, “We go, sometimes, to art for danger, to be riveted by experiencing the strange: by understanding suddenly how uncanny the familiar is. We go to be urged, shaken into reassuring thoughts we have taken for granted; to learn other ways of seeing, hearing. To be excited. Stirred. Disturbed.” These wise and beautiful words define and describe Titas as accurately as they do any work of art pursued with similar lofty intentions and realized with exemplary ability.

***

Years ago, this writer came across a strange piece in the then infrequently published bulletin of Nandan, the West Bengal Film Centre. Written in Bengali by one of the editors of the bulletin, the essay was in praise of Pather Panchali; no problem thus far. In translation, the closing lines would roughly read as follows; and here the trouble begins: “We have seen the film version of many great novels – Ghare Baire, Padma Nadir Majhi, Titas Ekti Nadir Naam, Ganadevata or Antarjali Jatra. But only Pather Panchali is a great film. Yes, only Pather Panchali.”

No, Titas Ekti Nadir Naam, too, is a great novel and a great film. It is nothing short of the pathetic that one should try to belittle one great work of film art to re-state the deserved greatness of another. One would have thought that the true cinephile’s mind and heart were spacious enough to hold many kinds of riches at one and the same time. Pray, when will the film-lover begin to exercise his birthright “to learn other ways of seeing, hearing”? There is nothing more unfortunate than to fail to recognize a masterpiece when one has the rare privilege of coming face-to-face with it. It is this kind of mindlessness, a blight of the spirit, a servitude of habit, that is responsible for driving some of our genuine talents to black moods, and worse, that they surely didn’t or don’t deserve.

Perhaps no one rued the fact of indifference or even hostility to Ghatak more than Satyajit Ray, going by the latter’s appreciation in glowing terms of his peer’s best films. “Ritwik had the misfortune to be largely ignored by the Bengali film public in his lifetime. Only one of his films, Meghe Dhaka Tara, had been well-received. The rest had brief runs, and a generally lukewarm reception from professional film critics. This is particularly unfortunate, since Ritwik was one of the few truly original talents in the cinema this country has produced. Nearly all his films are marked by an intensity of feeling coupled with an imaginative grasp of the technique of filmmaking. As a creator of powerful images in an epic style, he was virtually unsurpassed in Indian cinema. He also had full command over the all-important aspect of editing; long passages abound in his films which are strikingly original in the way they are put together. This is all the more remarkable when one doesn’t notice any influence of other schools of filmmaking on his work. For him, Hollywood might not have existed at all. The occasional echo of classical Soviet cinema is there, but this does not prevent him from being in a class by himself.”

Come to think of it, that these very special words were articulated long after Ghatak was dead is a matter of a special kind of sadness. If anything even remotely resembling this handsome tribute had been written or said when Ghatak was living, perhaps there would have been a world of difference in the response of those insufficiently educated people going by the name of “professional film critics” or for that matter, of the film-going public.

(Vidyarthy Chatterjee writes on cinema, society, and politics.)