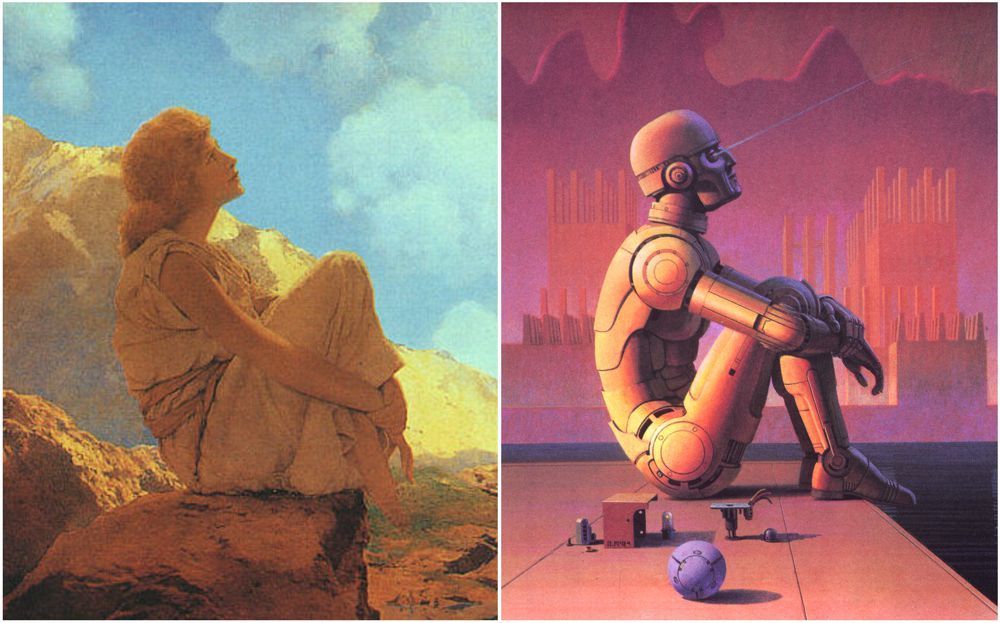

These are two very short science fiction stories by Isaac Asimov, the renowned American author. Both were written in the middle decades of the 20th century. Both acknowledge the technological achievements of humankind, and express an apprehension about its potential to be used in catastrophic and alienating ways.

As we mark 35 years of Chernobyl, 10 years of Fukushima and the world’s military powers sit on thousands of nuclear weapons, ecological crises like global warming, ocean acidification and others threaten to go into runaway mode. The irrationality and apocalyptic potential of capitalist society was never more apparent. The first story has become very fresh and relevant in this context.

In the early days of computers and modern telecommunications, the loss of education and social life, the alienating potential of digital education and interactions was feared. This fear has been expressed in the second tale. Life under the pandemic has made that story contemporary.

❈ ❈ ❈

I. Silly Asses

Naron of the long-lived Rigellian race was the fourth of his line to keep the galactic records.

He had a large book which contained the list of the numerous races throughout the galaxies that had developed intelligence, and the much smaller book that listed those races that had reached maturity and had qualified for the Galactic Federation. In the first book, a number of those listed were crossed out; those that, for one reason or another, had failed. Misfortune, biochemical or biophysical shortcomings, social maladjustment took their toll. In the smaller book, however, no member listed had yet blanked out.

And now Naron, large and incredibly ancient, looked up as a messenger approached.

“Naron,” said the messenger. “Great One!”

“Well, well, what is it? Less ceremony.”

“Another group of organisms has attained maturity.”

“Excellent. Excellent. They are coming up quickly now. Scarcely a year passes without a new one. And who are these?”

The messenger gave the code number of the galaxy and the coordinates of the world within it.

“Ah, yes,” said Naron. “I know the world.” And in flowing script he noted it in the first book and transferred its name into the second, using, as was customary, the name by which the planet was known to the largest fraction of its populace. He wrote: Earth.

He said, “These new creatures have set a record. No other group has passed from intelligence to maturity so quickly. No mistake, I hope.”

“None, sir,” said the messenger.

“They have attained to thermonuclear power, have they?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, thats the criterion.” Naron chuckled. “And soon their ships will probe out and contact the Federation.”

“Actually, Great One,” said the messenger, reluctantly, “the Observers tell us they have not yet penetrated space.”

Naron was astonished. “Not at all? Not even a space station?”

“Not yet, sir.”

“But if they have thermonuclear power, where do they conduct the tests and detonations?”

“On their own planet, sir.”

Naron rose to his full twenty feet of height and thundered, “On their own planet?”

“Yes, sir.”

Slowly Naron drew out his stylus and passed a line through the latest addition in the small book. It was an unprecedented act, but, then, Naron was very wise and could see the inevitable as well as anyone in the galaxy.

“Silly asses,” he muttered.

❈ ❈ ❈

II. The Fun They Had

Margie even wrote about it that night in her diary. On the page headed May 17, 2157, she wrote, “Today Tommy found a real book!”

It was a very old book. Margie’s grandfather once said that when he was a little boy his grandfather told him that there was a time when all stories were printed on paper.

They turned the pages, which were yellow and crinkly, and it was awfully funny to read words that stood still instead of moving the way they were supposed to – on a screen, you know. And then, when they turned back to the page before, it had the same words on it that it had had when they read it the first time.

“Gee,” said Tommy, “what a waste. When you’re through with the book, you just throw it away, I guess. Our television screen must have had a million books on it and it’s good for plenty more. 1 wouldn’t throw it away.”

“Same with mine,” said Margie. She was eleven and hadn’t seen as many telebooks as Tommy had. He was thirteen.

She said, “Where did you find it?”

“In my house.” He pointed without looking, because he was busy reading. “In the attic.”

“What’s it about?”

“School.”

Margie was scornful. “School? What’s there to write about school? I hate school.”

Margie always hated school, but now she hated it more than ever. The mechanical teacher had been giving her test after test in geography and she had been doing worse and worse until her mother had shaken her head sorrowfully and sent for the County Inspector.

He was a round little man with a red face and a whole box of tools with dials and wires. He smiled at Margie and gave her an apple, then took the teacher apart. Margie had hoped he wouldn’t know how to put it together again, but he knew how all right, and, after an hour or so, there it was again, large and black and ugly, with a big screen on which all the lessons were shown and the questions were asked. That wasn’t so bad. The part Margie hated most was the slot where she had to put homework and test papers. She always had to write them out in a punch code they made her leam when she was six years old, and the mechanical teacher calculated the mark in no time.

The Inspector had smiled after he was finished and patted Margie’s head. He said to her mother, “It’s not the little girl’s fault, Mrs. Jones. I think the geography sector was geared a little too quick. Those things happen sometimes. I’ve slowed it up to an average ten-year level. Actually, the over-all pattern of her progress is quite satisfactory.” And he patted Margie’s head again.

Margie was disappointed. She had been hoping they would take the teacher away altogether. They had once taken Tommy’s teacher away for nearly a month because the history sector had blanked out completely.

So she said to Tommy, “Why would anyone write about school?”

Tommy looked at her with very superior eyes. “Because it’s not our kind of school, stupid. This is the old kind of school that they had hundreds and hundreds of years ago.” He added loftily, pronouncing the word carefully, “Centuries ago.”

Margie was hurt. “Well, I don’t know what kind of school they had all that time ago.” She read the book over his shoulder for a while, then said, “Anyway, they had a teacher.”

“Sure they had a teacher, but it wasn’t a regular teacher. It was a man.”

“A man? How could a man be a teacher?”

“Well, he just told the boys and girls things and gave them homework and asked them questions.”

“A man isn’t smart enough.”

“Sure he is. My father knows as much as my teacher.”

“He can’t. A man can’t know as much as a teacher.”

“He knows almost as much, I betcha.”

Margie wasn’t prepared to dispute that. She said, “I wouldn’t want a strange man in my house to teach me.”

Tommy screamed with laughter. “You don’t know much, Margie. The teachers didn’t live in the house. They had a special building and all the kids went there.”

“And all the kids learned the same thing?”

“Sure, if they were the same age.”

“But my mother says a teacher has to be adjusted to fit the mind of each boy and girl it teaches and that each kid has to be taught differently.”

“Just the same they didn’t do it that way then. If you don’t like it, you don’t have to read the book.”

“I didn’t say I didn’t like it,” Margie said quickly. She wanted to read about those funny schools.

They weren’t even half-finished when Margie’s mother called, “Margie! School!”

Margie looked up. “Not yet, Mamma.”

“Now!” said Mrs. Jones. “And it’s probably time for Tommy, too.”

Margie said to Tommy, “Can I read the book some more with you after school?”

“May be,” he said nonchalantly. He walked away whistling, the dusty old book tucked beneath his arm.

Margie went into the schoolroom. It was right next to her bedroom, and the mechanical teacher was on and waiting for her. It was always on at the same time every day except Saturday and Sunday, because her mother said little girls learned better if they learned at regular hours.

The screen was lit up, and it said: “Today’s arithmetic lesson is on the addition of proper fractions. Please insert yesterday’s homework in the proper slot.”

Margie did so with a sigh. She was thinking about the old schools they had when her grandfather’s grandfather was a little boy. All the kids from the whole neighborhood came, laughing and shouting in the schoolyard, sitting together in the schoolroom, going home together at the end of the day. They learned the same things, so they could help one another with the homework and talk about it. And the teachers were people… The mechanical teacher was flashing on the screen: “When we add fractions ½ and ¼ …”

Margie was thinking about how the kids must have loved it in the old days.

She was thinking about the fun they had.