‘The struggle of man [humans] against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting,’ wrote Milan Kundera in one of his works.

This powerful quote is reminder of many things, of which one is the act of remembering. The very act of remembering is not a neutral act but laden with ideological considerations and biases. This hold truer when we remember historical events and figures of political importance. How we remember past events and figures, what are the things and acts that we omit or leave out from remembering and what we remember is motivated by our ideological considerations and political projects.

One such popular act of ritualised remembering is that of the great Santhal rebellion that took place in mid-19th century in British India.

Every year the Santhal rebellion and its leaders Sidhu and Kanhu Murmu are remembered in ritualistic way by different political parties and communities, all from different perspectives. But beneath all these different ways of remembering there lies a unitary theme; that the Santhal rebellion was one of the first expressions of revolt against the British colonial regime.

This framework, though true but limited, has become so dominant that the Santhal rebellion is now merely seen as a part in a series of similar such events that took place in colonial India.

This dominant understanding is informed by a nationalist framework in which almost every revolt in British India is interpreted only as anti-British revolt while other aspects of them are totally omitted from public memory. A strict and only location of the Santhal and other similar Adivasi revolts within the framework of national liberation struggle also reeks of cultural imperialism as it seeks to erase the cultural or identity aspects of these tribal revolts.

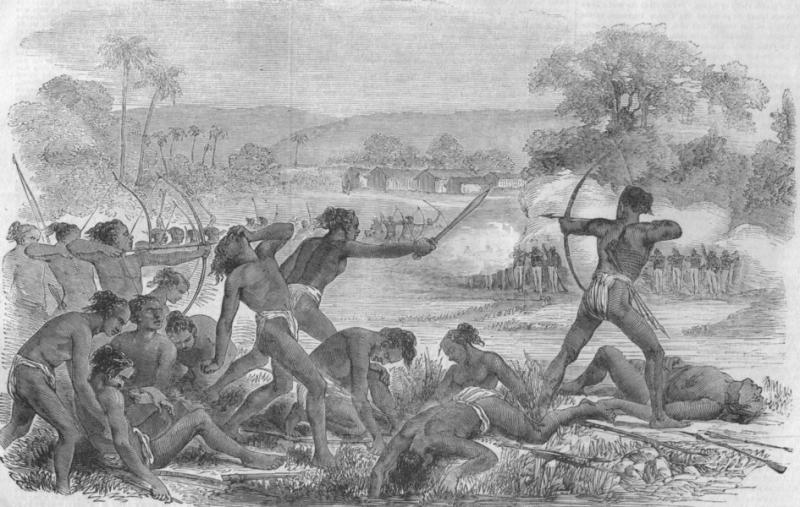

The Santhal rebellion began on June 30, 1855, and went on for almost six months before it was finally suppressed by January 3, 1856, leaving over 15,000 Santhals dead and over 10,000 of their villages destroyed. This great insurrection known as the ‘Hul’, was led by four brothers, namely Sidhu, Kanhu, Chand and Bhairav Murmu of village Bhagnadihi, under whom almost 60,000 Santhals mobilised with traditional weapons.

This rebellion – in spite of it having largely been woven around the theme of anti-British revolt – actually began as revolt against exploitation by Indian ‘upper’ caste zamindars, moneylenders, merchants and darogas (police officials), collectively known as ‘diku’, who had come to dominate the economic sphere of Santhal life.

The Santhals who originally spread over regions of present-day Bihar and West Bengal were relocated by the Britishers in the Rajmahal hill region between 1790 and 1810 following the great Bengal Famine of 1770 which had killed between 7 to 10 million people and had affected 30 million.

The reason behind the relocation of Santhal people was the demand for agricultural labour following the depletion of population in permanent settlement zones of Rajmahal and Jungle Mahal hills. Sponsored by the British and local landlords, Santhal people entered the area and began clearing the jungles. They were employed as agricultural labourers or got land on lease. The region in which the Santhals were relocated came to be known as ‘Damin-i-koh’.

The Damin region soon became a centre of Santhal socio-cultural life and attracted Santhals from neighbouring districts. As late Adivasi scholar has Abhay Xalxo noted, ‘The formation of the Damin came as a great blessing to the Santhals. They thought that at last they would have a homeland of their own and would be able to live an independent life and preserve their culture and identity’.

But this blessing did not last long as non-tribals from adjoining areas started to settle in the Damin and began to oppress and exploit the Santhals and other tribals groups of the region.

Giving a vivid description of the exploitation of Santhals by merchants, traders and mahajans who belonged mostly to the Hindu community William Wilson Hunter, a colonial bureaucrat wrote:

“Hindu merchants flocked thither every winter after harvest to buy up the crop, and by degree each market-town throughout the settlement had its resident Hindu grain dealer. The Santal was ignorant and honest; the Hindu was keen and unscrupulous. Not a year passed without some successful shopkeeper returning from the hill-slopes to astonish his native town by a display of quickly-gotten wealth, and to buy land upon the plains.”

The Santhals were exploited and robbed in and out, right and left without any remorse from merchants and traders. Hunter further writes:

“The Santal country came to be regarded as a country where a fortune was to be made, no matter by what means, so that it was made rapidly… hucksters settled upon various pretences, and in a few years grew into men of fortune. They cheated the poor santal in every transaction. The forester brought his jars of clarified butter for sale; the [merchants] measured it in vessels with false bottoms; the husbandman came to exchange his rice for soil, oil, cloth and gum-powder; the merchants used heavy weights in ascertaining the quantity of grain light ones in weighing out the articles given in return. If the santal remonstrated, he was told that salt, being an excisable commodity, had a set of weights and measures to itself.

“The fortunes made by traffic in produce were augmented by usury. A family of new settlers required a small advance of grain to eke out the produce of the chase while they were clearing the jungle. The dealer gave them a few shillings worth of rice, and seized the land as soon as they had cleared it and sown the crop…from moment the peasant touched borrowed rice, he and his children were the serfs of the corn merchant.

“No matter what economy the family practiced, no matter what effort made to extricate themselves; stint they might, toil as they might, the [mahajans] claimed the crop and carried on a balance to be paid out the harvest. Year after year the Santhal sweated for his oppressor. If the victim threatened to run off the jungle, the usurper instituted a suit in the courts, taking care that the Santhal should know nothing of it till the decree had been obtained and the homestead were sold, omitting the brazen household vessels which formed the sole heirloom of the family. Even the cheap iron ornaments, the outward tokens of female respectability among the Santhals, were torn from the wife’s wrist…’

In the wake of these varied forms of exploitation, there emerged two systems of bonded labour in Santhal territory, namely kamioti and harwahi. Under the first system, the borrower had to work for the mahajan till the repayment of the loan; under the second the borrower had in addition to personal services, to plough the mahajan’s field whenever required till the loan was repaid. The terms of the bond were so stringent that it was practically impossible for the Santhal to repay the loan during his lifetime.

Apart from oppression from merchants, mahajans and traders, the Santhal also faced oppression from the zamindars and capitalist agriculture. The zamindars and landlords extracted huge rents from the Santhal peasants while those Santhals who were employed in indigo plantation worked long hours and with extremely low wages. In such an extreme situation, the Santhals tried to petition to the British government and approached courts, but without any respite. Every time they went to the court or tried the official channel, they were met with disappointment.

This extreme form of oppression and neglect from British administration gave birth to social banditry in 1854 when a band of Santhals under the leadership of Bir Singh Manjhi, and others like Domin Manjhi and Kewal Pramanik, began to attack moneylenders and zamindars and distribute the loot among the poor Santhals.

Bir Singh claimed to have been granted magical power by one their deities, Chando Bonga. The wide popularity of these bandits and frequency of attacks alarmed the moneylenders and zamindars who appealed to the royal family. This lead to police action and subsequent humiliation of those social bandits, as well as a few affluent Santhals who were accused of being robbers themselves. It was in this background that the Santhals raised the banner of revolt in 1855.

The brothers Sidhu and Kanhu Murmu claimed to have received word from Thakur Bonga, who urged them to revolt against the exploitative powerful. Prior to the decisive moment of revolt, the Santhal villages were replete with rumours derived from religious myths. Abhay Xalxo has listed four such rumours in his article ‘The Great Santhal Insurrection (Hul) of 1855-56’. These played an important role in developing communal solidarity among the Santhals just before the rebellion began.

On the night of June 30, 1855, some 10,000 Santhals gathered at Bhagnadihi where the orders of Thakur Bonga were read to them. Sidhu and Kanhu announced that god had directed them to: “Slaughter all the mahajans and darogas, to banish the traders and zamindars and all rich Bengalis from their country, to sever their connection with the Damin-i-koh, and to fight all who resisted them, for the bullets of their enemies would be turned to water”.

The rebels demanded that Britishers and native exploiters withdraw from the Damin-i-koh, and if not, they would declare a war on them sanctioned by god.

The rebellion, apart from acting against oppression and exploitation was also inspired by the political project of building and establishing an independent Santhal Raj. In the course of rebellion, the Santhal people developed their own infrastructure of governance. The leaders of the rebellion appointed themselves as governors of the region and many Santhals were appointed in the capacity of darogas, subordinate officers and naibs. The Murmu brothers promised deliverance from oppression and a utopian Santhal Raj free from exploitation, oppression and the diku.

This from of rebellion where a divine authority is cited by rebels who have a utopian vision, is labelled a ‘millenarian movement’ by social scientists. As historian Michael Adas illustrates in his work Prophets of Rebellion (1979), millenarian movements were a consistent feature of colonial societies, especially among tribal societies all across the world during the colonial period. For example, the Pai Marie movement of the Maoris in New Zealand, the Cargo cult of Java islands, the Maji-Maji rebellion in east Africa, all displayed it. Even in India, the Munda rebellion and the Thana Bhagat movement have been described as millenarian movements. Invoking divine authority for the purposes of social transformation has been an important feature among oppressed and exploited communities throughout history.

The Santhal rebellion began with the killing of a daroga on July 7, 1855. The policeman had gone to arrest the Santhal leaders. The police had been bribed by local mahajans, who had been ill at ease upon hearing about the huge Santhal gatherings. They asked the policemen to arrest the Santhal leaders under false changes of theft and dacoity. When the daroga, with his party, reached to arrest the Murmu brothers, Santhals attacked him.

This began the ‘hul’ which spread like wildfire in neighbouring regions.

Santhals, along with local peasants, attacked local zamindars and moneylenders and looted their property and cattle. They also captured the treasuries of nearby royal families. Meanwhile, local zamindars and moneylenders helped the British forces quell the revolt by providing them with shelter and other daily provisions. The Nawab of Murshidabad even provided the British army with war elephants and trained soldiers.

On the other hand, the rebels were helped by a large number of non-tribal and poor mainly belonging to ‘lower’ castes groups. Dairy farmers helped the rebels with provisions, while blacksmiths accompanied the rebels and helped them with their weapons. The Santhal rebellion also had a class component to it as oppressed groups united to fight against economic and cultural oppressors.

The British suppressed the movement with utmost brutality. Sidhu was hanged by the British army on August 19, 1855, while Kanhu was arrested on in February 1856. After this, the movement subsided. Even though this great insurrection lasted only for six months, it had a huge impact upon the Adivasi community and served as an inspiration for other Adivasi revolts.

Today the Santhal revolt along with Munda rebellion, Kol rebellion, Thana Bhagat movement and others are mainly remembered as anti-British revolts and while doing so the important component of ‘internal colonialism’ is glossed over.

The British rule – though extremely exploitative on economic fronts – brought some respite for the ‘lower’ castes by opening up opportunities for them under promises of liberal democracy. For the ‘upper’ caste Hindus, the British rule provided an opportunity to reclaim their cultural and economic dominance over Indian society, which they had lost since the beginning of the medieval period. For Adivasis, the story of colonial and postcolonial rule has only been a story of continuous exploitation and erasure of their way of life.

(Harsh Vardhan and Shivam Mogha are research scholars at Centre for the Study of Social Systems, JNU. Courtesy: The Wire.)