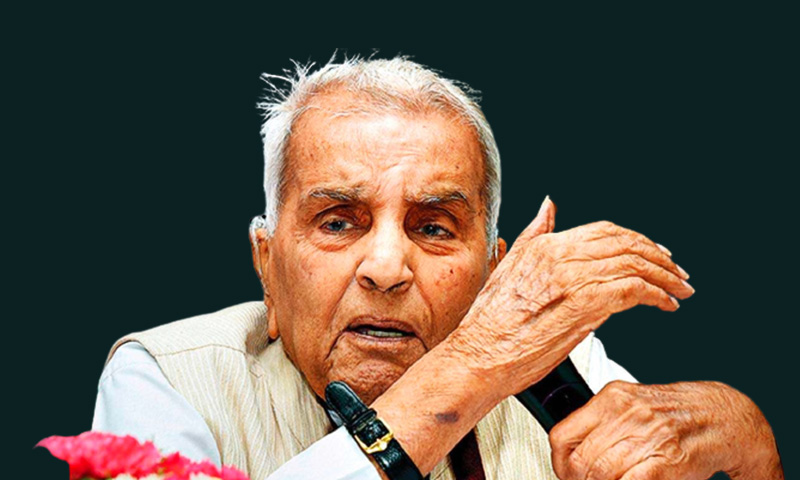

He had forbidden us to call him ‘Justice Sachar’. So I began to call him Sachar Saheb. Four days after his death, I sit down to write this tribute. The personality of Sachar Saheb was like a masterpiece, epic in its dimensions. A classic personality in this absurd period! In a tribute like this, written for the media, there is little scope to remember him in that ethereal form. It can only be an attempt to understand his thoughts, concerns, anxieties and work in a pragmatic perspective.

Sachar Saheb passed away on 20 April 2018. He would have been 95 years old this 22 December. My friend Ravikiran Jain, president PUCL, used to say with much assurance that Sachar Saheb will live to be a hundred. Considering his strong desire to live, it seemed very likely. Before the last bout of illness, he was capable enough to take care of his health on his own whenever he fell ill. But for the last three months, it seemed that he has made up his mind that it was time for the abandonment of the body. Now he will live among us through memories, thoughts and work.

Tributes to Sachar Saheb have appeared continuously after his demise in newspapers, magazines, portals and condolence meetings. In these tributes he is remembered as a capable and successful lawyer and the Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court who made unabated efforts and waged constant struggles in order to protect civil rights, human rights, constitutional and democratic institutions and the interests of deprived and oppressed sections of the society. Sachar Saheb’s name had become more well known during the last 10–12 years due to the Sachar Committee Report and its recommendations. While paying him tributes, most people—friends, colleagues and admirers—do not forget to mention and discuss this unique contribution of Sachar Saheb.

In my knowledge, hardly any written or verbal tribute to Sachar Saheb has discussed his role in contemporary political thought and political activism. (An exception to this trend is the tribute by Tanveer Fazal, published in ‘The Wire’). It cannot be said that journalists and scholars are unaware of his political ideology and activism. Then, what could be the reason that associates who profusely praise his work do not mention his political affiliations? Why this omission?

Despite being seriously ill, Sachar Saheb continued to pen his views, and wrote his last article ‘India Needs Draupadi and Not Savitri’ only a few days before his death, which was published in the English weekly Janata on 1 April 2018. Just a few days prior to this article, he wrote ‘No Conflict Between Hindi and State Regional Languages’ on March 3. The subject matter of these two articles relate significantly to Dr. Lohia’s views. Sachar Saheb’s writings and work are often perceived to be rooted and inspired by Dr. Lohia’s political philosophy and struggle. It would be pertinent to mention here that in most of his articles and statements, the earlier ones as well as these last two, Sachar Saheb invariably referred to socialist leaders, Dr. Lohia in particular. His deep commitment to the cause of PUCL had its genesis in the fact that JP had established it.

Sachar Saheb became a member of Socialist Party from the time of its formation in 1948. He was also the secretary of the Delhi Pradesh unit. He played an active role in the programs organised by the party. In May 1949, while participating in a demonstration in front of the Nepali Embassy in Delhi, he was arrested along with Dr. Lohia and stayed in jail for one month and a half. In 2008–09, several senior and young socialist leaders/activists from across the country, including Sachar Saheb, held meetings in different cities for the re-establishment of the Socialist Party. Consequently, in May 2011, the Socialist Party was reinstated as Socialist Party (India) in Hyderabad. Since then, Sachar Saheb had worked tirelessly for the expansion of Socialist Party despite his senior position and age.

In sunshine, rains, storm and cold, he used to walk in the streets with the party workers and participate in demonstrations/meetings/conventions organised by the party. He used to call the workers all over the country to get information about party activities. Any party worker could meet him at home at any time without prior information. In the previous assembly elections in Delhi, the Socialist Party had fielded a candidate from the Okhla legislative constituency. Sachar Saheb’s house falls in the same area. He addressed street meetings for the candidate and distributed pamphlets walking through crowded streets. During my candidature from East Delhi, he was active throughout, from filing of nomination to the last day of the election campaign. In politics like life, Sachar Saheb was trustful and a believer. However, many, including socialists, with whom he interacted were not always trustworthy. Like Kishan Patnaik, he also had a naive belief that the NGO people can be a part of transformative politics!

Sachar Saheb had immense faith in socialism, secularism, democracy, civil rights, individual freedom and the non-violent mode of protest against injustice. Behind Sachar Saheb’s multi-faceted role was his deep faith in democratic socialism and socialist vision. The report and recommendations of the Sachar Committee should also be understood from this perspective. Without considering this perspective of his life, there is no meaning in praising his personality.

What then is the reason that many journalists and scholars who pay homage to his memory forget to mention the shade of his political inclination? The main reason for this omission appears to be that Sachar Saheb was against the neo-liberal policies being implemented in the country by successive governments for the last nearly three decades now. There is almost a general consensus in the civil society regarding these policies. The Socialist Party (India), of which Sachar Saheb was a founding member, has repeatedly stated through its policy document and resolutions that if the public sector is destroyed for establishment of the private sector then the constitutional and democratic institutions too will be destroyed. Secularism and democracy cannot be saved by abandoning the value of socialism contained in the Constitution. Blind adherence to neo-liberal policies promotes communalism, superstitions and idiocy on the one hand, whereas on the other hand it promotes blind nationalism. This understanding and analysis of the Socialist Party is inconvenient for most secular intellectuals and leaders. They take leave of their own responsibility by merely placing the blame on the RSS for ‘fascism’. In doing so they free the neo-liberalist/neo-imperialist forces to wreak havoc on the working masses of the country.

First Bhai, and now Sachar Saheb. Within a fortnight, two stalwarts of socialism have passed away. This is not the loss of the Socialist Party only. It is an irreparable loss to the politics of values instilled and nurtured from the freedom movement, the Constitution of India and the socialist movement. ‘The struggle will continue!’ With this resolution the Socialist Party salutes its revolutionary leader.