India’s peasantry is under attack. But this attack comes not only in the form of measures explicitly targeted at them, such as the three farm Acts; equally destructive are policies that systematically depress demand in the economy as a whole. These undermine the survival of the peasantry, and loosen their hold on their lands.

The effect of depressed demand on the peasantry

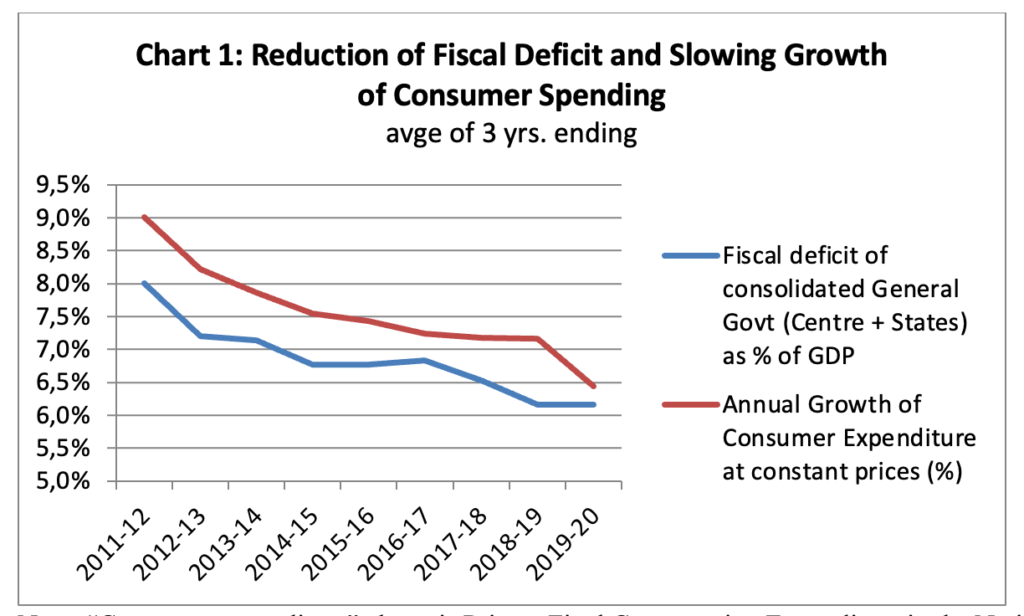

The Indian economy was slowing long before Covid-19. The underlying reason for this was the lack of demand. Lack of demand is a basic feature of India’s existing political economy, in which vast numbers of people eke out a bare subsistence, even as a tiny minority flourish. It seemed for a time that the demand problem had gone away, as the economy grew frenetically during 2004-11. However, this spell of growth was on a narrow base of demand, and was distorted and unsustainable; its legacy was the ensuing slump and ‘hangover’ of bad debts. Specific Government policies in recent years – Demonetisation, the Goods and Services Tax, and the drive to reduce the fiscal deficit by slashing Government spending – depressed overall demand further.

Thus “when the pandemic hit, the economy was going through the most prolonged slowdown in the post-liberalisation period…. The longevity of the slowdown (2017-18 to 2019-20) surpassed not only that of the 1990s or early 2000s, but even the Global Financial Crisis and the slowdown in 2011-12 and 2012-13.”[2]

In the rural areas, this slowdown meant that peasants faced worse terms of trade (i.e., the prices of their purchases rose faster than the prices of their output); rural labourers’ real wages shrank (i.e., a day’s wages bought less than before); and the problem of ‘underemployment’ worsened (the hours of employment per working person fell).

Then, with the advent of Covid-19 in 2020, the Government imposed the world’s harshest lockdown, shutting virtually all informal sector enterprises. This had a devastating impact, as the proportion of workers in the informal sector in India is among the world’s highest. Despite this, India’s Central government was among the world’s most tight-fisted in its expenditure during the lockdown: its additional spending in the crisis year was a paltry 2 per cent as a proportion of the previous year’s GDP. State governments bore the brunt of dealing with the crisis, but faced an even worse squeeze on their finances. Hence total (Centre plus states) government consumption expenditure in 2020-21 grew at its lowest rate in seven years[3] – at a time when a sharp increase was desperately needed.

Even after the lockdown was lifted, the Central government’s policy of suppressing its own spending continues to systematically maintain a drought of demand in the economy as a whole. The Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE), commenting on the severe cuts in the April-June 2021 quarter, talks of it as the “Government’s puzzling reluctance to spend”.[4]

In recent months, several commentators, hunting for evidence of economic recovery, have detected or projected a revival of rural demand. They base this on the fact that agricultural output was good last year, and that sales of large firms actually grew last year in the rural areas. However, much of that growth of the market for large firms may not have been due a growth in the overall market. Rather, small firms and informal businesses, which sell goods cheaper, were closed in the lockdown, and consumers had nowhere else to turn to except the goods of large firms. CMIE data show that during the December 2020 quarter, small firms’ sales shrank massively even as the top firms actually grew: “Large companies are not only better placed to ride out of the storm but also gain by cannibalising markets of the withering smaller companies.”[5]

Two emergency measures did partly cushion the rural areas during 2020. First, the public distribution system distributed, for free, an additional 31.5 million tonnes of foodgrains between April and November 2020 (beyond its normal distribution). Second, the Government spent an extra Rs 50,000 crore was spent on the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), beyond the budgeted figure of Rs 65,000 crore. However, even if we unrealistically assume zero leakages in the above schemes, it must be remembered that the loss of rural incomes in 2020-21 was much larger than these schemes. The loss of consumer expenditure nationwide in 2020-21 was over Rs 4.2 lakh crore at current prices.[6] A large portion of this loss would have been in the rural areas, where 68 per cent of the population resides, and which probably housed a greater percentage during 2020.

In 2021, too, some revival was inevitable after the lows touched in May-June 2021 (which was the most intense period of the ‘second wave’ in the rural areas), and this is already visible. The monsoon this year was considered normal at the all-India level. Further, the Government has resumed distributing five kg of free grain for the period May-November 2021. The steep cut in the MGNREGS budget for 2021-22 (by one-third over last year’s figure) will cause a loss of employment generated under the scheme, but the CMIE does find some signs of a pick-up in overall rural employment in September 2021.[7]

However, this revival may dissipate quickly, as the underlying reality in the rural areas is grim.

It is important to keep in mind the following:

- The income of peasants does not depend solely on whether the crop is good; it also depends on whether crops are sold at remunerative prices. This in turn depends, to a large extent, on the overall level of demand in the economy.

- Similarly, the growth of agricultural labourers’ wages does not depend solely on farm output. It also depends on the overall market for manual labour, since many workers work in both agriculture and in other sectors such as construction.[8] Thus both agricultural and non-agricultural wages partly depend on the overall level of employment and demand in the economy.

- The lockdown on the vast informal sector in 2020 (in manufacturing, construction, trade, and other services), combined with the drought of Government spending, has inflicted long-term damage, and many small enterprises will not recover.

- Most components of overall demand in India are likely to remain weak.[9]

Summary

In the following article, we show that, while agricultural output is said to be doing well, that does not mean those who work in agriculture, i.e., peasants and agricultural labourers, are doing well. As a larger number of people desperately looked for ways to earn a living, the income per person working in agriculture actually declined. Most of the new entrants to agriculture were women, working as unpaid helpers in family operations. Their new work merely added to their existing burdens, not to their income.

While wages per day briefly went up at many places in the wake of the lockdown and resultant labour shortages, there was less employment available overall, so the total earnings of working people in the rural areas would have fallen. In the following months, real rural wages began falling again. Indeed their wages have been on a downtrend since 2018. Given that wage workers in the rural areas are the very bottom of the income ladder in India, a fall in their incomes is a silent catastrophe.

Moreover, as overall consumer demand in the economy has slowed down, the terms of trade for the peasantry have worsened, and the income from farming of crops has declined in real terms (after discounting for inflation).

Now that there is an unprecedented fall in demand, the portents for the peasantry are grim. Both agricultural prices and rural wages are likely to remain depressed. This is likely to make it even harder for poor peasants, who constitute the great bulk of the peasantry, to keep their heads above water. The existing grave debt crisis among the poor peasantry has been worsened with the developments of the last two years. There are signs that peasant households are losing their small hoards of gold; a section of them may also lose their lands, which may be transferred to other agrarian classes, whether they be moneylenders, traders or large landowners. In this way the Government’s extraordinary restriction of its own expenditure ties in with the aim of its three farm Acts, which is to oust the poor peasantry.

I. Agricultural Output Unaffected by the Lockdown

‘Resilient’ is the catchword of the Government’s flagship economic document, the Economic Survey 2020-21. The words ‘resilient’ and ‘resilience’ make 74 appearances in the text of the Survey. This conveys the sense of an inner strength that can bounce back even after intense stress.

In fact, in 2020 India’s economy performed the worst of all major economies worldwide. The IMF’s latest estimate of world GDP growth in calendar year 2020 is -3.3 per cent. Within this, its estimate for “emerging markets and developing countries” is -2.2 per cent; for South Asia, -6.5 per cent; and for India within that, -8 per cent. Even this understates the collapse in India’s economy, since the IMF depends on the Indian government’s GDP estimates. India’s official statistical machinery grossly underestimates the lockdown-related losses to the vast informal sector, where the overwhelming majority of India’s non-agricultural workers earn their living.

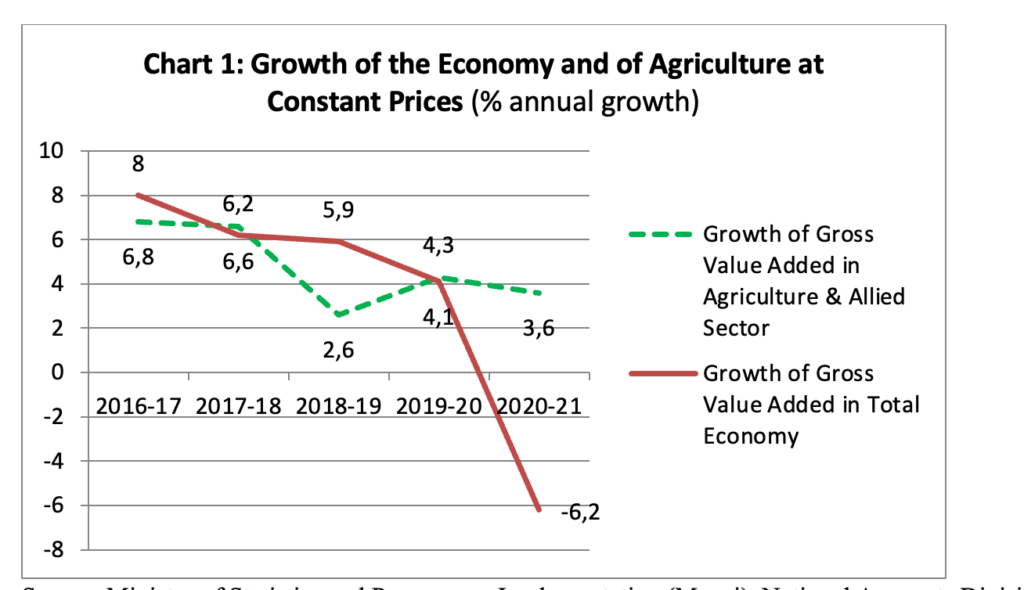

But on one score India’s official sources claim a great success: They say India’s agriculture in 2020 was unaffected by the Covid-19 epidemic itself or by the associated lockdowns. The Government’s Economic Survey 2020-21 said that “Agriculture sector has remained the silver lining”. The latest official estimates put growth of agriculture at 3.6 per cent in 2020-21, even as the rest of the economy plunged.

And so the Survey tells us that:

The resilience of India’s agriculture sector can be seen from the fact that despite the COVID-19 pandemic, its performance in output was strong… Rural demand has remained resilient empowered by the government’s thrust on the rural economy and infrastructure in previous years… While the difficulties created by COVID induced lockdowns adversely affected the performance of the non-agricultural sectors, the agriculture sector came up with a robust growth rate of 3.4 per cent at constant prices during 2020-21.

We are told that this happy state continues in 2021-22, despite the second ‘wave’. The Reserve Bank’s report on the State of the Economy (August 2021) points to the “resilience of the rural sector on brightened agricultural prospects,” and claims that rural demand has been “upbeat”.

Indeed, it would seem from the latest official estimates that agricultural output in 2020-21 largely escaped the effects of the lockdowns. Foodgrains output are estimated to have achieved another record, and oilseeds and sugarcane too appear to have done reasonably well. The area under kharif crops rose by 4.8 per cent in 2020-21 over the earlier year,[10] and the current year, 2021-22, may nearly match that performance. Of course this “success” was largely due to the monsoon and the Government’s decision not to lockdown agricultural operations themselves, rather than any beneficial policies.

When the rulers speak of the performance of agriculture (or for that matter any sector of the economy), they separate that performance from the condition of those who work it. What of the latter, the peasants and agricultural labourers? Their story is very different. It is one of a steep drop in incomes, and a desperate attempt to make ends meet.

(to be continued)

Notes

[1] Fiscal deficit data from Economic Survey, different years. Private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) data for 2011-12 to 2019-20 from National Statistical Organisation; for PFCE for the years 2009-10 and 2010-11, we have not used the controversy-ridden official back series, but the back series proposed in the Report of the Committee on Real Sector Statistics, National Statistical Commission, July 2018, which appears to be more realistic.

[2] Azim Premji University, State of Working India 2021: One year of Covid-19, Centre for Sustainable Employment, 2021, p. 37. It defines ‘slowdown’ as consecutive quarters of slowing growth.

[3] National Statistical Organisation, Annual Estimates of GDP at Constant Prices, 2011-12 Series, September 1, 2021 release. Government final consumption expenditure (GFCE) grew 2.9 per cent in 2020-21, compared to an average of 7.9 per cent during 2014-15 to 2019-20.

[4] Manasi Swamy, “Government’s puzzling reluctance to spend”, https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=20210903152315&msec=056

[5] Mahesh Vyas, “Firm size matters”, March 4, 2021, https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2021-03-04%2012:08:25&msec=793&ver=pf

[6] The Private Final Consumption Expenditure of 2019-20, expressed in 2020-21 prices, would have been Rs 127.3 lakh crore. But the actual PFCE in 2020-21 was Rs 123.1 lakh crore in 2020-21 prices. The difference is Rs 4.2 lakh crore. If we take into account 1 per cent population growth, the difference would be Rs 5.5 lakh crore.

[7] Mahesh Vyas, “Employment increases in rural India”, October 4, 2021, https://cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=20211004120642&msec=123

[8] Although the labour market in India is not properly unified one, and is stratified by region, gender, castes/communities, specific trades, etc., the overall level of demand for labour does have an impact on the general level of wages.

[9] Export demand alone might grow, precisely because demand in the rest of the world economy is better than in India. However, of the other components of aggregate demand,

(a) The growth of private consumption has been slowing over the last decade.

(b) For lack of consumer demand, private investors have refused to make fresh investments.

(c) Meanwhile, the Government has refused to increase its own spending substantially, for fear of annoying international investors.

[10] https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=1658997

(Research Unit for Political Economy is a Mumbai based trust that analyses economic issues in simple language.)