(The previous two parts of this article have been published in the previous two issues of Janata Weekly blog.)

Pushed Over the Edge

With the massive depression of demand that has taken place due to the lockdowns and the Government’s refusal to spend, many rural households that were earlier struggling to keep from falling would have been pushed over the edge.

(1) Reduced food consumption

Long before the Covid-19 lockdowns, it was well-known that food consumption in India was abysmally low. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS) of 2015-16 confirmed that child undernutrition rates in India are among the highest in the world, much higher than in some countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Nearly half of all children in India under the ages of three years of age were either underweight or stunted. The results from the next round of NFHS (2019) are so far available only for states that account for half the population. However, these are particularly disturbing. They reveal that in most of these states there has been a worsening in childhood stunting (low height for age), wasting (low weight for height), and underweight (low weight for age). As always, figures for undernutrition in the rural areas are worse than urban ones.

Another important pointer is the National Sample Survey (NSS) of households’ consumption expenditure. The latest such survey, covering the year 2017-18, found that household consumption expenditure had fallen in real terms in the six years since the earlier survey (2011-12). This appears to be the first such instance since the mid-1960s. While consumption expenditure stagnated in the urban areas, it fell sharply in the rural areas. As a part of this, food expenditure remained at the same level in the urban areas, but fell a massive 10 per cent in the rural areas. (In an unprecedented action, the Government suppressed this NSS report, claiming implausibly that there were problems of data quality.)[1]

Then came the lockdown of 2020. A number of unofficial surveys by various organisations documented the impact of the lockdown; 76 such surveys (as of April 2021) were compiled by the Centre for Sustainable Employment at Azim Premji University. Reviewing these surveys, Jean Drèze and Anmol Somanchi found that there was a sharp drop in food consumption by working people during the lockdown; moreover, follow-up surveys found that food consumption of these households, particularly of nutritious items, did not return to its earlier levels even after the lockdown.[2]

For example, the Azim Premji University Covid-19 Livelihoods Phone Survey (CLIPS) interviewed people in two rounds, April-May 2020 and October-December 2020, i.e., during and after the nationwide lockdown. In the second round, 87 per cent of rural respondents said their food intake had decreased during the lockdown, but even after the lockdown was lifted, the intake of 59 per cent of rural respondents remained lower than before the lockdown.

Surveys of rural households by the Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) in April and October 2020 similarly reported cutbacks in food intake during the lockdown, which persisted even after the lockdown was lifted. In October 2020, 45 per cent of respondents consumed less food than before the lockdown, due to reduced earnings, loss of employment, and rise in food prices. Worst affected were Scheduled Caste and manual workers. Nutritious foods, such as egg, meat, fish and green vegetables, were dropped from the diet.[3]

While consumption also declined in the urban areas, the decline in food consumption in the rural areas is particularly striking, given the good harvest of foodgrains. Food was available, but working people lacked the income to buy it. The problem was not one of production, but of production relations.

(2) Indebtedness

When people’s incomes fail to meet their consumption needs, they are driven into debt. Drèze and Somanchi note:

In the absence of adequate relief measures, there was a surge in indebtedness in 2020, and also some distress sale of household assets. The proportion of sample households that were constrained to borrow or defer payments during the national lockdown varied between 38% and 53% in three major surveys. The corresponding proportions in follow-up surveys later in 2020 were lower, but still close to 20% (for the concerned reference period). Predictably, the compulsion to borrow was stronger for poorer households…. [A] significant minority of households were also constrained to sell or mortgage assets in 2020, during or after the national lockdown.[4]

The FAS October 2020 survey of rural households similarly found that 35 per cent of respondents had taken loans, but only 6 per cent of these loans were from the formal sector. Poorer households took formal sector loans largely from micro-finance institutions or by pledging gold with commercial banks. Based on this survey, one study comments:

Poor peasant and manual worker households across the study villages reported that they had taken loans to meet increased costs of cultivation in the kharif season. The loans were taken from input dealers, moneylenders, local traders, and others at interest rates ranging from three to six per cent per month…. In contrast, landlords and rich capitalist farmers and rich peasants were in a better situation – most managed to get loans from commercial and cooperative banks, besides meeting additional expenses from their own savings. (emphasis added)[5]

According to the CLIPS survey, 41 per cent of rural respondents took loans to cover consumption costs during the lockdown, and 23 per cent sold or pawned assets in order to do so.

Gold loans: One sign of the scale of distress in both urban and rural areas is the steep rise in the personal loans people took against gold from commercial banks. Such loans rose 43 per cent between August 2019 and August 2020, and another 66 per cent by August 2021.[6] In all, thus, they rose 137 per cent in two years.

However, personal gold loans are only a fraction of total gold loans extended by banks; the bulk of gold loans by banks are agricultural gold loans. Although the RBI does not release data for total gold loans by banks, data released by Bank of Baroda (BoB)[7] may give us an idea of the proportions. BoB’s personal gold loans stood at Rs 1,117 crore in June 2021, but its agricultural gold loans were more than 20 times larger, at Rs 23,202 crore. Agricultural gold loans made up nearly a quarter of all BoB’s agricultural credit.

In 2019 itself, a Reserve Bank of India Internal Working Group had pointed to the fact that a sizeable share of ‘agricultural loans’ were being taken against gold, perhaps for consumption purposes.[8] It is all the more likely that, in the Covid-19 period, many distressed rural households would have diverted part of their agricultural gold loans for consumption purposes. For example, BoB saw its agricultural gold loans jump by more than a third in the Covid-19 period, and by June 2021 such loans made up a considerably bigger share of its total agricultural lending than a year earlier.[9]

In recent years, ‘non-banking financial corporations’ (NBFCs) specialising in gold loans, such as Muthoot Finance, Manappuram Finance, and IIFL Finance have grown rapidly, peaking at an estimated 27 per cent compound annual growth rate in the last two years. They now account for an estimated Rs 1.1 lakh crore of loans.[10]

However, gold loans by both banks and NBFCs are perhaps dwarfed by the gold loans extended by private moneylenders, for which data are not available. An RBI report noted:

In addition to a growing organised gold loans market, there is a large long-operated, unorganised gold loans market which is believed to be several times the size of organised gold loans market. There are no official estimates available on the size of this market, which is marked with the presence of numerous pawnbrokers, moneylenders and land lords operating at a local level. These players are quite active in rural areas of India and provide loans against jewellery to families in need at interest rates in excess of 30 percent. These operators have a strong understanding of the local customer base and offer an advantage of immediate liquidity to customers in need, with extreme flexible hours of accessibility, without requirements of any elaborate formalities and documentation. However, these players are completely un-regulated leaving the customers vulnerable to exploitation at the hands of these moneylenders and pawn-brokers.[11]

(3) Implications of indebtedness

The growth of indebtedness has several implications. First, the perpetuation of low demand. These indebted persons would need to repay their loans, with interest, from their incomes. As a result, even after the lockdown their consumption may remain below the earlier level. Overall consumer demand would remain depressed, and the economy would find it hard to recover to its earlier level.[12]

Recall that the earlier level was itself very low: in the last pre-Covid year, 2019-20, the economy had slumped dramatically, with the manufacturing sector shrinking 2.4 per cent and construction growing just 1 per cent. The principal reason for this slump was lack of demand. Now a return to even that low level of demand may be obstructed by the debts incurred during the lockdown.

It might be argued that the amount of demand emanating from these poor people would be small compared to the demand from the better-off, and hence its economic impact would be minimal. However, it is not only the quantum of demand, but the particular type of demand, which has an impact on the economy, particularly on employment. The goods the working people purchase are predominantly simple goods of mass consumption, often produced in the informal sector, and with little import content. Vast numbers of workers are employed in the sectors which make these goods, so a reduction in demand from the poor in turn leads to a sizeable loss of jobs. This vicious cycle of reduced demand of the working people and falling employment in the informal sector is precisely the pattern we have been witnessing in recent years.

(4) The burden of debt

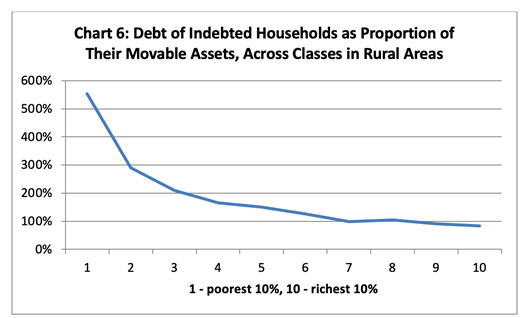

In such a depressed economy, a certain number of indebted persons would be unable to repay their debts, and would lose their assets. Their first line of defence would likely be to sell movable assets such as livestock, equipment and jewellery (i.e., not land and buildings). Such movable assets, however, make up only 8.5 per cent of the total assets of rural households. The debts of indebted rural households (both cultivators and non-cultivators) in 2019 were 126 per cent as large as their movable assets.[13] The poorer the indebted household, the higher is the ratio of its debt to its movable assets (see Chart 6 below). This condition would no doubt have worsened during the last 18 months.

Source: Calculated from All India Debt and Investment Survey 2019, Table A11R. 1 to 10 refer to deciles of households according to size of assets. Movable assets are assets other than land and buildings.

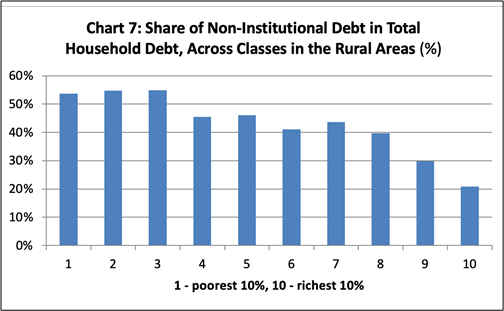

Poorer rural households are forced to take a greater share of their loans from what are called ‘non-institutional sources’ – such as moneylenders, input dealers, chit funds, landlords, relatives and friends, which we can abbreviate to ‘moneylender+’ debt. Part of the reason for this is that poorer households lack access to most ‘institutional’ sources, such as banks and cooperatives, which we can call ‘bank+’ debt.[14] For at least the bottom 30 per cent of rural households, the share of such ‘moneylender+’ debt is higher than that of ‘bank+’ debt (Chart 7). (In reality the share of ‘moneylender+’ debt is likely to be larger, but respondents to such surveys tend not to reveal this. A survey found that even in Punjab, the state with the most extensive network of banks extending agricultural credit, 39 per cent of credit to farm households is given by non-institutional sources, and among small and semi-medium farmers, the percentage rises to over 48 per cent.[15])

Source: All India Debt and Investment Survey 2019, Table A28R. 1 to 10 refer to deciles of households according to size of assets.

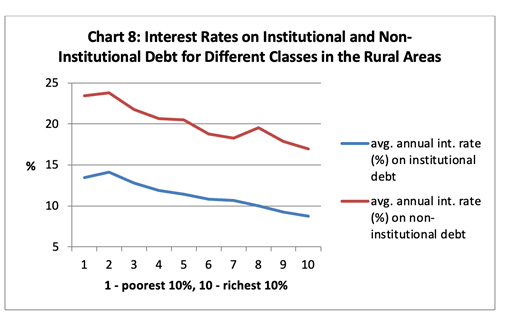

This means the poorer rural households pay a higher rate of interest overall: the average interest rate on rural ‘bank+’ loans is 11 per cent, but for ‘moneylender+’ debt, it is nearly double that, at 20 per cent.[16]

A further twist is that the poorer the household, the higher is the interest rate charged by the lender, whether it be a bank or a moneylender. Thus the poorest rural households borrow from ‘bank+’ sources at an interest rate of 13 per cent, while the wealthiest borrow at 9 per cent; the poorest households borrow from ‘moneylender+’ sources at 23 per cent, the wealthiest borrow at 17 per cent.

Source: Calculated from All India Debt and Investment Survey 2019, Table A28R. 1 to 10 refer to deciles of households according to size of assets.

It should be noted that bank lending in the rural areas is done almost wholly by public sector banks and cooperative banks; private sector bank branches are hardly to be found in rural India. Now the Government has announced its plans to privatise most of the public sector banks, which will leave the field in the rural areas clear for various types of moneylenders, both traditional ones and new types.

Two such new types of moneylenders are hardly less usurious than traditional moneylenders: the average interest rate charged by micro-finance NBFCs is 24.4 per cent;[17] that of gold loan NBFCs is at least 22 per cent[18] and is probably higher.[19] The RBI recently announced plans to remove all limits on the interest rates charged by micro-finance NBFCs.[20]

(5) Loss of assets

As distress deepens, many households are already unable to repay their gold loans, as a result of which their gold is auctioned. NBFCs such as Manappuram Finance and IIFL Finance regularly advertise in newspapers for the auction of gold; a single such advertisement, spread over two pages of the Business Standard, contains details of over 5,000 lots, and announces that auctions will be conducted at “the respective talukas/centres from where such loan was availed…. All defaulting borrowers have been duly intimated…”. Manappuram auctioned Rs 1,500 crore of gold in April-June 2021, more than three times the amount in the previous quarter.[21]

The FAS survey cited earlier found that 16 per cent of the respondents had been forced to sell assets; this was particularly the case with members of Scheduled Castes, some of whom had been forced to sell their small land holdings.

Selling land is the last resort for most rural households, since work outside agriculture is insufficient on its own to meet the subsistence requirements of the family. In the latest official survey of farm households,[22] the average such household had a monthly income of just Rs 10,218. Of this, about 40 per cent came from wages, 37 per cent from crop production, 15 per cent from farming of animals, and 6 per cent from non-farm business.

Table 2: Average monthly income (Rs.) from different sources per agricultural household during July 2018 – June 2019

| Wages | 4,063 |

| Net income from crop production | 3,798 |

| Net income from farming of animals | 1582 |

| Income from leasing out of land | 134 |

| Net income from non-farm business | 641 |

| Total | 10,218 |

Source: Situation Assessment of Agricultural Households and Land and Holdings of Households in Rural India 2019, National Sample Survey 77th Round.

Diametrically opposed interpretations of the same data

From the above data, some commentators have concluded that the bulk of farm households – what are termed ‘marginal farmers’ – are not really “serious” farmers, since they derive more of their income from wages than from farming crops. An editorial in the Indian Express bluntly concludes: “The government should stop obsessing over ‘marginal farmers’…. Farming is best left to those who can do it well. Better fewer, but better.”[23]

Scholars of the Centre for Policy Research present a marginally more refined version of this view. Examining the data of the latest NSS of farm households, they conclude that only 39 per cent of farm households are actually “serious” farmers, and call for targeting agricultural policy in favour of this section: “Not everyone can or needs to be a farmer”.[24] They calculate that only 0.2 per cent (that is not a typo) of farm households in Jharkhand meet their criterion of seriousness. Applying their “better fewer, but better” rule would remove 99.8 of agricultural households in Jharkhand, 99 per cent in West Bengal, 98 per cent in Tamil Nadu, and 94 per cent in Odisha. Indeed this is precisely the thinking that has driven the Government’s agricultural policies, including the recent farm Acts. The process of demand depression, indebtedness and loss of assets we have described above also drives toward such an outcome.

Actually, the interpretation of the data in Table 2 differs radically depending on one’s class standpoint. From the standpoint of the working people, the same data show that even households which include wage workers have clung on to farming activities, since their income from wage work alone has not sufficed to meet their family’s needs. For example, wage income was no doubt the largest source of income for agricultural households owning just 0.01-.40 hectares, but it brought them less than Rs 4,500 a month, or less than Rs 30 per day for each member of the household.[25] If they could have earned more income from wage work alone, they might have done so, but in the absence of decently-paying wage work, they needed farmland for survival. Survival is a deadly serious matter for them.

Secondly, it is well established, including by official committees, that peasants receive unjustifiably depressed prices for their produce. The present regime’s Committee on Doubling Farmers’ Income began by stating in the Foreword to its 2017 report that “despite higher productivity and production… The markets do not assure the farmer of remunerative returns on his produce.” The Committee found, for example, that the per hectare returns on paddy cultivation are low in the case of most states; indeed, taking the broadest measure of cultivation costs, known as the “C 2” measure, the returns were actually negative in six states (Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Odisha, and West Bengal), which account for well over a third of the country’s output. The Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) reports that for the last five years (2016-17 to 2020-21), the all-India average market price of paddy has remained below the Minimum Support Price (MSP); this despite the fact that the MSP itself is not based on the broadest measure of costs. In the case of crops for which there is no Government procurement, the situation is worse.

In other words, peasant incomes from farming get grossly depressed due to the existing economic and social set-up; this is further compounded by current State policies. Now, if the peasants were to receive higher returns on their produce, the figure of household income from farming crops and animals in Table 2 above would rise, and so, too, would the share of farm income in their total income. In that case, they would suddenly turn out to be “serious” farmers by the criterion of the scholars mentioned above. It is strange that the very fact that peasants are squeezed and underpaid can be used by scholars to term them “unserious” farmers.

Moreover, possession of farmland provides multiple forms of sustenance which may not be immediately apparent from such survey data. For one, farm households, and marginal farm households in particular, keep a share of the crop for their own consumption. (The NSS finds that farm households in 2018-19 retained 36-54 per cent of various cereals – paddy, wheat, ragi, jowar, and bajra.[26]) This would have been more expensive to have purchased from the market. A foothold in the village also provides access to village common property resources, including fodder, firewood and uncultivated (wild) plants; we know that such resources supply a large proportion of rural families’ basic needs.[27] And given the hostile conditions for the labouring poor in urban India, the village offers workers’ families a refuge for rearing children, annual leave and retirement. The importance of having access to land was further underlined during the Covid-19 lockdown, when millions of workers returned to their villages, and found some meagre subsistence there.

There is a significant caste dimension, too, brought out by the same survey: 82 per cent of Scheduled Caste agricultural households fall in the ‘marginal holdings’ bracket. If they were to lose their meagre plots, their dependence on upper castes for a livelihood would increase, and correspondingly their social oppression. And while Scheduled Tribes have larger plots of land than Scheduled Castes, crop yields on their lands are low; moreover, if they sell any part of their crops, the price they receive for it is low, and hence their agricultural output is accorded a low money value by the survey. Thus the survey values the farming income of Scheduled Tribes lower than their wage income. In this fashion Adivasis, the social segment that is most dependent on agriculture (and forestry), wind up failing the scholars’ test, and at least two-thirds of them would be deemed “unserious” farmers.

In the view of international agencies and the Indian rulers, the poor peasantry are ‘unviable’, indeed they are the cause of the crisis of India’s agriculture. In effect, their solution to the problem of “doubling farmers’ income” is to reduce the number of “farmers” to a third, or less, along the lines of “better fewer, but better”. It is a class war from above.

However, in defiance of the wishes of international agencies and the Indian rulers, these poor peasants (marginal and small farm households, accounting for 70 and 18 per cent, respectively, of the total) continue to cling to their land, and struggle to make it productive, even under very adverse circumstances. A sizeable number of them lease in land to augment their inadequate plots.[28] Over the course of the three surveys (2002-03, 2012-13 and 2018-19), the number of agricultural households has not fallen.

Two paths

There has been a 60-year debate on whether small farms in India are more or less productive per hectare than large farms, and numerous economists have tried their best to prove the case against small farms, without much success. The entire discussion is at any rate based on a mistaken framework, and diverts from the real questions of the conditions and relationships within India’s agriculture.[29] But we wish to point out certain simple truths.

First, a process which effectively ousts marginal farm households, whether by acquiring their meagre plots outright or, as outlined above, by destroying their economy to the point where they themselves relinquish their lands, will impoverish tens if not hundreds of millions, since it is a hard reality that no other sector of the economy is as yet able to provide them a full-fledged livelihood. This ousting would in turn trigger a further depression in demand.

Of course a large share of those at present ‘employed’, or rather, underemployed, in agriculture need jobs outside agriculture. But those jobs must be created first through a democratic and national development process, and absorb workers from agriculture. Neoliberal theorists instead demand that those working in agriculture be simply ousted, and expect that the very unemployment of the oustees will attract the creation of jobs for them. (Such theorists do not believe that such a thing as involuntary unemployment exists.)

The alternative to this devastation is a social, economic and political process to strengthen marginal farm households and enhance their resources, making their agriculture more productive, remunerative and genuinely resilient; increase their collective access to land and common property resources such as water; and free them of multiple parasitic extractions. This would not only lift vast numbers out of poverty, but generate demand for simple goods, the production of which can generate widespread industrial employment. When achieved through a broad social movement, this would lay the base for collective efforts to improve the land’s productivity, as well as to spin off village-level industrial enterprises which could employ under-employed workers from agriculture, particularly during the slack agricultural season. Such an alternative, however, can only emerge through a fierce struggle and broad social transformation.

In the absence of such a struggle, what lies ahead is an alienation of peasant assets. Unlike the case of private corporate firms or the State acquiring lands, here the mechanism of loss of land would be through other agrarian classes, such as moneylenders, traders and larger landholders. The blanket term “farmers” blurs more than it reveals. The survey of farm households – defined as those who earn at least Rs 4,000 a year from agriculture – finds that 73 per cent of them own just 25 per cent of the land; at the other end, 2.6 per cent of the richest households own 20 per cent of the land. In other words, an average household in the latter group owns almost 23 times the amount of land of a household in the former group – even going by official data, which generally do not reveal the full extent of land inequalities. Both sections are termed “farmers”; but the process described above would transfer assets from the poorer set of farmers to the richer.

(concluded)

Notes

[1] Somesh Jha, “Consumer spend sees first fall in 4 decades on weak rural demand: NSO data”, Business Standard, November 14, 2021. While the fall in consumption expenditure was sharper among the higher income sections, the growth rate was negative for all segments of the population; “what is really hurtful for the condition of the poor is that the already low average consumption levels of the poorest deciles have declined even further in the period under review.” S.Subramanian, “What is happening to rural welfare, poverty and inequality in India?”, The India Forum, December 6, 2019.

[2] Jean Drèze and Anmol Somanchi, “The Covid-19 Crisis and People’s Right to Food”, May 31, 2021, https://www.im4change.org/upload/files/Covid%20and%20the%20right%20to%20food%20%28final%2031%20May%29%284%29.pdf

[3] Tapas Singh Modak, Sandipan Baksi and Deepak Johnson, “Impact of Covid-19 on Indian Villages”, Review of Agrarian Studies (RAS), January-June 2020, and S. Niyati and R. Vijayamba, “Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Food Security and Indebtedness in Rural India”, RAS, January-June 2021.

[4] Drèze and Somanchi, op. cit.

[5]

[6] Mimansa Verma, “In the pandemic, distressed Indians pledged gold worth Rs 62,926 crore for loans”, Quartz India, October 4, 2021.

[7] Bank of Baroda, Performance Analysis Q1, FY22, https://www.bankofbaroda.in/shareholders-corner/presentation-made-to-analyst .

[8] Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Report of the Internal Working Group to Review Agricultural Credit, 2019, p. 27.

[9] Bank of Baroda, op. cit. The share of agriculture gold loans in total agricultural loans of BoB rose from 19.5 per cent in June 2020 to 23.9 per cent in June 2021.

[10] Crisil press release “Gold loan NBFCs set to clock 18-20% growth in current fiscal”, October 12, 2021, “https://www.crisil.com/en/home/newsroom/press-releases/2021/10/gold-loan-nbfcs-set-to-clock-18-20-percent-growth-in-current-fiscal.html

[11] RBI, Report of the Working Group to Study the Issues Related to Gold Imports and Gold Loans NBFCs in India, 2013, p. 108.

[12] Prabhat Patnaik, “Destitution, Hunger and the Lockdown”, People’s Democracy, May 23, 2021.

[13] Calculated from Table A11R, All India Debt and Investment Survey 2019, National Sample Survey 77th Round.

[14] Other reasons may include their ties to employers, landlords, input dealers, and the like.

[15] Sukhpal Singh, Shruti Bhogal, and Randeep Singh, “Magnitude and Determinants of Indebtedness among Farmers in Punjab”, Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, April-June 2014.

[16] The interest rate on moneylender debt is higher, but non-institutional borrowings also include interest-free loans from family and friends, which brings down the average.

[17] RBI, Consultative Paper on Regulation of Microfinance, June 2021, p. 22.

[18] Crisil press release, “Gold price fall not so much a worry for NBFCs, but banks need to be watchful”, April 12, 2021. https://www.crisil.com/en/home/newsroom/press-releases/2021/04/gold-price-fall-not-so-much-a-worry-for-nbfcs-but-banks-need-to-be-watchful.html

[19] RBI, Report of the Working Group to Study the Issues Related to Gold Imports and Gold Loans NBFCs in India, says that the “major loan portfolio of gold loan NBFCs covers average interest rate of 24 to 26 per cent and only 2 per cent of their portfolio is in the interest rate of 12 per cent.” p. 181. Moreover, the effective interest rate is likely to be even higher, given that these firms pre-emptively auction gold in case of a fall in the gold price, or failure to service the loan according to schedule. If the sum obtained in the auction is higher than the sum due by the borrower, the firm pockets the difference.

[20] RBI, Consultative Paper.

[21] Mimansa Verma, op. cit., citing Aparna Iyer, “Behind Manappuram’s gold auctions, a tale of rising stress”, Mint, August 11, 2021.

[22] Situation Assessment of Agricultural Households and Land and Holdings of Households in Rural India 2019, National Sample Survey 77th Round.

[23] Editorial, “Farmers’ future”, Indian Express, September 21, 2021. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/editorials/indian-farmers-monthly-income-agricultural-household-7523346/

[24] Harish Damodaran and Samridhi Agarwal, “Counting the kisan”, Indian Express, October 4, 2021.

[25] Situation Assessment of Agricultural Households.

[26] Ibid.

[27] “Common Property Resources in India”, NSS Report no. 452, January-June 1998.

[28] In Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal, leasing-in is dominated by holdings under 2 hectares. In Haryana, Karnataka and Punjab leasing-in is dominated by holdings over 4 hectares. In Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana, the picture is mixed, but the share of small holdings leasing in land is sizeable.

[29] Krishna Bharadwaj, “Notes on Farm Size and Productivity”, Economic and Political Weekly, Review of Agriculture, March 1974.

(Research Unit for Political Economy is a Mumbai based trust that analyses economic issues for the common people in simple language.)