August, 1946. Mayhem in Calcutta (now Kolkata). In some of the city’s Hindu-dominated areas, Muslims were being savaged or plain butchered. In some other localities where Muslims lived in large numbers, Hindus were being maimed and murdered. There had been a particularly ghastly pogrom of poor Muslim slum-dwellers in the north-eastern neighbourhood of Nikashipara, dominated by Hindu traders from an adjoining state, and an eye-witness was recounting the grisly incident to some students and teachers of Calcutta University.

Men, women and children had been corralled into a blind lane and then a huge ring of fire had been lit carefully around them so that they would all be charred to death. Some desperate mothers, crying and screaming, begged for their babies to be spared and tried to throw the infants over to safety outside the ring while they perished themselves. But the zealots gathered around the fire, picked the babies up and threw them meticulously back into the raging inferno.

Among the listeners was a shocked Professor Sushobhan Sarkar, the doyen of history teaching in India in the 1940s and 50s, who exclaimed: “My god! Surely Bengali boys were not involved in this horror?”

“But why shouldn’t they?”, thundered another middle aged listener, a formidable classics scholar himself. “Don’t Bengali young men have blood in their veins? Aren’t they men?” The gentleman in question was a devout Hindu, of course, as the Oxford historian Tapan Roychowdhury, then a student and present among the listeners that day, recalled in his memoirs years later. We don’t get to know the worthy’s name, though there are enough hints about his identity in Professor Roychowdhury’s account of that dreadful August in Calcutta.

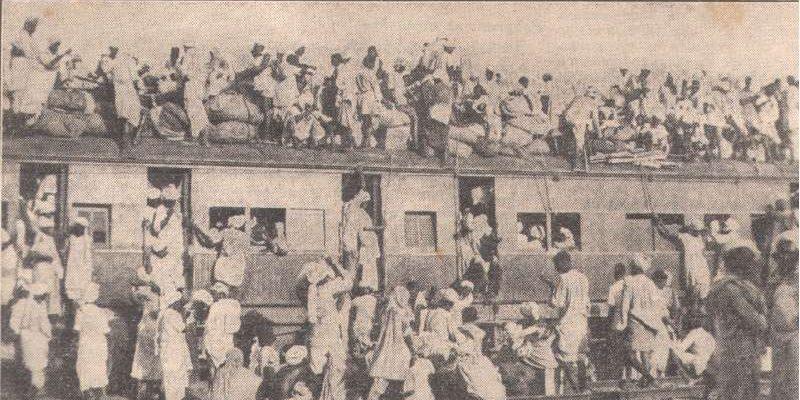

As sickening as it turned out to be, the 1946 bloodbath was yet only a preview of the holocaust that Partition would bring in its wake. The scars seared into people’s minds by Partition were more hideous and more permanent, the passions it released more revolting, than any other episode in our recent history. Even the highly-regarded scholar gloating over the ‘virility’ of rioting Bengali youth during the 1946 conflagration would have been put in the shade by the unspeakable savagery August 1947 happened to unleash.

For anyone caught in the Partition maelstrom, it was never again going to be easy to look sanely at religions other than their own; and it would be even more difficult for them to concede that the communities at war in 1947 – principally the Hindus and the Muslims — were equally culpable for the carnage. All of a sudden, humankind seemed to be plumbing the depths of beastliness – and indeed to revell as it sploshed about those dark depths. And all of this was happening for the sake of – at any rate, in the name of – religious purity and piety.

Because religious faith was so central to those cataclysmic events of seventy-four years ago, it was inevitable that our collective consciousness of the Partition would be made up of several disparate narratives, often clearly at odds with one another. Trauma, hurt and bewilderment jostle in these narratives with pity, compassion and a craving for healing. Raw anger and a poised forbearance are often just a small step away from each other here.

It must be said, however, that the ‘formal’ chronicles that have hitherto held the greater appeal for the public imagination are nuanced enough to foreground the essential humanity, even of men caught in the throes of a terrible tragedy. And this is only as it should be. Recounting the endless horrors of the Partition without an understanding either of the wellhead of those horrors or of their possible mitigation, can not only not bring closure, it actually allows forgotten lesions to fester. This is why there was such consternation all round when the Indian Prime Minister, in his speech to the nation on India’s 74th Independence Day, announced that henceforth August 14 would be observed as ‘Partition Horrors Remembrance Day’.

What was the purpose of this formal reopening of old wounds, many asked in dismay. Why recall the horrors, the depravities, rather than the processes of healing and reconciliation and the countless men and women who died struggling to bring that healing about? Surely the Prime Minister did not want Indians to gloat, à la the venerable classics professor in Calcutta in 1946, over the horrors of the Partition on this side of the border? Or did he?

The Prime Minister may choose to invoke what god he will, but the common citizen of the country has several unforgettable Partition narratives to fall back upon instead – for solace. These works of art are pivoted on the insanity of the conflagration, on its utter absurdity and they point unwaveringly to one fact: when we choose to define identity by religion, we do so only at our own peril.

Here we briefly look at three such works, a film and two short stories, which distil the essence of a humane response to the tragedy. The horrors the Prime Minister wishes us to never forget loom in the backdrop of these stories alright – sometimes, they burst on to the centre of the stage, too – but in the end, they are overshadowed by something immeasurably bigger and grander – the sense that the human spirit is immutable.

The M.S. Sathyu movie, Garm Hawa (‘Scorching Winds’, 1974) revolves around a fairly well-to-do – and socially well-placed – Muslim family in immediately post-Partition Agra struggling to come to terms with the changing realities of their environment. The family members’ contented, happy lives begin to wilt under increasing social and political pressures. The head of the family, the gentle and dignified Salim Mirza, adores Gandhi and believes their vicissitudes of fortune will go away soon. He is unhappy that members of the extended family begin to leave India in search of peace and prosperity in Pakistan.

Increasingly, others join the exodus, too, until his own elder son follows suit along with his wife and child, leaving everyone shell-shocked. Meanwhile, Mirza’s successful business suffers one setback after another. Orders get cancelled mysteriously, his bank and even private money-lenders he had dealt with for many years, shut the tap on his business. A social boycott stiffens around the family, Mirza’s elderly mother dies heartbroken after the family is forced out of their sprawling ancestral home and his daughter’s marriage hopes are cruelly dashed, prompting her to take her own life. With a heavy heart, Mirza decides that he has reached the end of his road in the country he was born, grew up and lived in all his life.

Together with his wife and younger son, he departs for the railway station to take the train to Pakistan. On the way, their tonga pulls up as it comes abreast of a long procession of young men, their voices raised in support of communal harmony and economic justice. Mirza’s son decides that he wants to join the procession too. He will stay back in India and be part of the battle against inequality, he declares. Mirza also ponders the choice and then steps out of the tonga himself. His mind is made up; he will not leave either. The film ends with the question that Mirza rhetorically asks of his wife, simply but clearly, as he abandons the idea of migrating to Pakistan: “For how long can a man live his life in isolation from fellow men, after all?”

It is a story with few frills, completely untouched by didacticism or polemic. A calm, assured handling of the powerful central narrative drives the film’s message home with remarkable effectiveness; that it is worth one’s while to try and preserve one’s faith in humankind’s capacity for goodness, even at the worst of times. The scalding winds of hate and intolerance will tail off someday and the kingdom of hope will be reclaimed by man once again.

This measured tone of hopefulness finds a striking expression in the noted Bengali novelist-storyteller Samaresh Bose’s 1947 short story Adaab (‘Greeting’). One night in curfew-bound Dhaka in undivided, Partition-time Bengal, with the air heavy with the stench of death, two strangers bump into one another at an intersection of two narrow city lanes. An upturned rubbish bin, behind which both cower in fear for their lives, is all that separates them and neither knows if the other man is a Hindu or a Muslim. Neither dares let the other in on that secret, for who knows when that knife will inevitably come out!

Slowly the two get talking, however. Both are desperately poor. The Muslim boatman had gone shopping for the Eid festival and then got caught in the mayhem for several days, unable to return to his wife and kids who he knows must be worried sick. The Hindu millworker is a little better informed about life and about the politics of communal violence, but he also doesn’t know when he can see his family again. As the night wears on, the two men duck stray bullets and the patrolling mounted police, who are known to be trigger-happy. The boatman is desperate; he just must go home. The millworker begs him to not risk his life, but the boatman is determined to take the chance. He sets out warily and as he lunges for the safety of a dark lane nearby, an officer shoots him dead, leaving the millworker distraught.

Two men who had been mortally scared of one another to begin with, had yet managed to forge a brief bond of togetherness under the shroud of a murderous night, but the bond snapped as the forces of ‘law and order’ intervened. The two men had not even bothered to find out each other’s names, but that didn’t stop them from knowing, albeit for a few short hours, that they shared in a common humanity.

Toba Tek Singh (1955) is one of Sadat Hasan Manto’s last published short stories. In it, Manto posits the perfect inanity of tying a man’s nationality to the religion he happened to have been born into. Post the Partition, Indian and Pakistani authorities formalised the exchange of persons who are perceived to ‘legitimately’ belong to this country or the other. At a certain point, the turn also comes for the inmates of mental institutions to undergo this nationality drill. At the Lahore lunatic asylum, one long-time resident goes by the name of Toba Tek Singh, which is really what the village he hails from is called, his true name being Bishen Singh. A Sikh, he is adjudged to be an automatic candidate for a transfer to India, but Singh is far from happy. Nobody can tell him how he was chosen for this honour and no one seems to know for sure if Toba Tek Singh is going to be part of India or of Pakistan. He is tormented by the thought of being bundled out to a strange country, for in his mind both India and Pakistan are alien lands. He resists his dislocation in every which way he can but, in the end, he is pushed out of the asylum, taken to the border separating the two countries and asked to move over to India.

The old man does not budge and stands resolutely “in no-man’s-land on his swollen legs like a colossus”. He keeps standing there all through the long night and, just before sunrise, he screams and collapses in a heap to the ground, dead.

“There, behind barbed wire, on one side lay India, and behind more barbed wire on the other side, lay Pakistan. In between, on a bit of earth which had no name, lay Toba Tek Singh. “

We might be asking for too much if we were to expect the Indian Prime Minister to be familiar with these three works of art – or, for that matter, with any of them. But someone should tell him that his countrymen don’t need to be reminded of the Partition – at any rate by puny men not capable of the kind of capacious imagination which only can show us the human way to remember such a tragedy.

(Anjan Basu is a Bengaluru based journalist. Article courtesy: The Wire.)