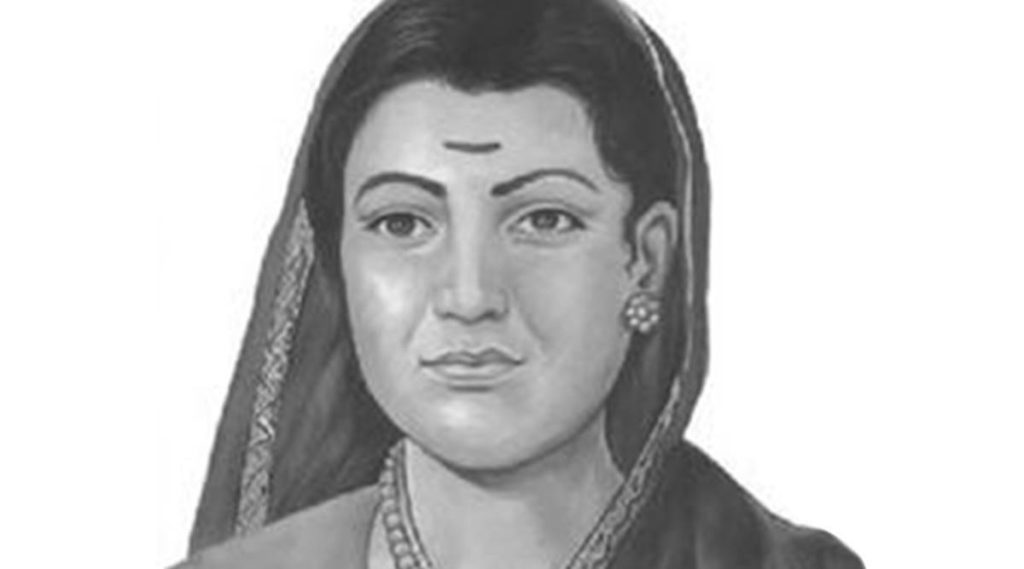

(In memory of Savitribai Phule, India’s first female teacher, who passed away on March 10, 1897.)

“Go, get education…” was Savitribai Phule’s appeal to women, in particular, and to people from the backward castes. She exhorted them to get an education as a means to break free from the shackles of socially-constructed discriminatory practices.

Savitribai was born on January 3, 1831, in Naigaon village in Maharashtra. She is formally recognised as India’s first female teacher. Savitribai played a pivotal role in women’s empowerment with the support of her husband, Jyotirao Phule (Jyotiba).

Born in a family of socially backward Mali community, Savitribai was illiterate when she married to Jyotiba at the tender age of nine. Fortunately, Jyotiba strongly believed in the power of education in removing social inequalities. He decided to start this revolution at home by teaching his wife to read and write, much against the family diktat. Initially, he taught her when she brought lunch for him in the field.

Later, Jyotiba admitted Savitribai to a teachers’ training Institute in Pune. After the training, Savitribai started teaching girls at Maharwada in Pune. Here, Sagunabai, Jyotiba’s mentor and also an activist, supported Savitribai’s efforts in this direction. Later, the couple along with Sagunabai, started their own school at Bhide Wada, which became India’s first girl’s school run by Indians. The school started with the nine girls, but the number increased to 25 gradually. Later, three more schools were opened for girls in Pune, with nearly 150 students altogether.

The couple introduced several innovative measures in teaching with a special focus on curriculum and teaching methods. They introduced stipends for students to motivate them to attend school. Also, regular parent-teacher meetings were arranged to educate parents on the importance of education. Special emphasis was given to subjects like English, science, mathematics and social studies. Consequently, the number of girls in their schools became higher than the boys enrolled in government schools in Pune. However, the enrolment of students from the untouchable community angered orthodox upper-caste Hindus. So, they tried to close these schools. First, they spread rumours about Savitribai; her husband would die prematurely due to her schooling, her food is changing into worms and also that educated women start writing letters to unknown men. When these tales didn’t discourage Savitribai, they started attacking her on her way to the school by throwing cow dung, eggs, tomatoes and stones at her. Undeterred, Jyotiba advised her to carry an extra sari in her bag, so that she can wear a fresh one while teaching in the school. Gradually, Savitribai gained the courage to respond to these insults, saying, “Your efforts inspire me to continue my work. May god bless you.” However, this public hooliganism stopped one day after Savitribai slapped a trouble monger and this act of her became sensational news across Pune.

Still, the conservatives found another way to stop the couple. They put pressure on Jyotiba’s father to throw them out of the house. According to them, it was a sin to educate women and the children of backward castes, as written in the holy scriptures. Out on the streets, the couple were accommodated by a close friend, Usman Sheikh and his family. His sister, Fatima Begum Sheikh, was already literate. Encouraged by her brother, Fatima accompanied Savitribai at another teacher training programme. Later, Fatima went on to become India’s first Muslim woman teacher. After the training, both of them started a school at Usman Sheikh’s residence.

Encouraged by improved enrolment, the couple opened a total of 18 schools for girls across Maharashtra from 1848 to 1852. Recognising this feat, the British government honoured them. Afterwards, the couple opened a night school for women and the children of those from the working-class community. They set up 52 free hostels for poor students across Maharashtra.

Besides education, the couple involved themselves in several social service activities. On September 24, 1873, they set up Satya Shodhaka Samaja, a platform which was open to all, irrespective of their caste, religion or class hierarchies, with the sole motto to bring about social equity. As an extension, they started, ‘Satya Shodhaka Marriage’ where the marrying couple has to take a pledge to promote education and equality. Likewise, widow re-marriage was also encouraged. Simple ceremonies without priests solemnising the wedding were conducted. Awareness programmes against dowry were also organised. They also dug a well at their courtyard for untouchables, who had no access to public drinking water facilities.

Savitribai, a true feminist, set up Mahila Seva Mandali to raise awareness among women against child marriage, female foeticide and the sati system. At the time, widows were often sexually exploited and pregnant widows suffered even more physical abuse and humiliation. To address this problem, the couple set up ‘Balyata Pratibandak Gruha’, a childcare centre for the protection of pregnant widows and rape victims. Savitribai also encouraged the adoption of children borne out of such sexual abuse. She opened an ashram for widows and orphans. She organised a boycott by barbers against the tradition of head tonsuring of widows. Savitribai appealed to women to come out of the caste barriers and encouraged them to sit together at her meetings.

When Jyotiba died in 1890, Savitribai set a new precedent by lighting her husband’s pyre, amidst all opposition. After his death, she dedicated all her time to the activities of Satya Shodhaka Samaja.

Savitribai was a renowned poet too and she published two poetic collections, Kavya Phule and Bhavan Kashi Subodh Ratnakar. Besides this, she edited Jyotiba’s speeches into a volume and published it in 1856.

In 1897, when Maharashtra was hit by Bubonic Plague, she responded quickly by setting up a clinic for patients with the support of her son, a medical professional. She dedicated all her time and resources at their service and also served free meals daily to nearly 2,000 children of the affected families. One such day, when she physically carried an infested child to the hospital, she too got infected. Consequently, Savitribai died on March 10 of the same year.

In commemoration of Savitribai, the University of Pune was renamed as Savitribai Phule Pune University in 2015. Her birthday is celebrated as “Balika Din” in Maharashtra every year.

Complete women’s empowerment is still a distant dream in India. While celebrating her legacy, we must also remember the contributions of her husband Jyotiba, who dreamt of equity for women and people of lower castes, as well as Fatima Begum Sheikh, her friend and colleague and also Sagunabai, Jyotiba’s mentor for their wholehearted support.

(The writer is Assistant Professor of English at Tumkur University. Article courtesy: The Indian Express.)