✫✫✫

Rahat Indori, the Poet Who Broke Through Conventions and Spoke Directly To the Public

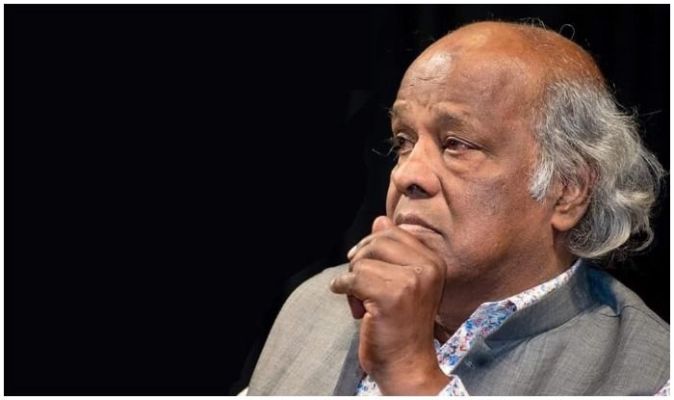

Danish Husain

It was the early 1980s. My father was a mushaira buff. He would procure audio cassettes of mushairas and listen to them on loop. When VCRs became widespread in our living rooms, he was excited. Now he could get video recordings of the mushairas and watch them for hours.

In one such recording, there was this new young poet, unconventional in his style and syntax, provocative, a complete performer, and challenging the grammar of mushaira etiquettes, yet the crowd seemed to be loving him. His choice of words was unusual. As said in Urdu literary parlance “Asaatza ne nahin baandha hai,” or the masters have not woven it into the poetic syntax. But his words had a great connect with the audience. And his style, maverick like, was completely over the top. When my poet uncle and aunts, traditional and conservative in their form and style, saw the performance, they disapproved of it.

But my dad, himself a great performer who would often recite shers with even greater bluster and elan in private mehfils or Muharram majlises, seemed to be loving it. I was intrigued. The young, impressionable me asked him who is this poet? With much glee, he said, this is Rahat Indori.

Rahat Indori burst on to the poetry scene in the mid-1970s and soon he made a mark for himself on the Mushaira scene. From early on, he understood the format of mushaira and figured out a way to challenge the standard practices in mushaira. No wonder his PhD dissertation was ‘Urdu Mein Mushaira’, awarded to him in 1985 from Bhoj University, Madhya Pradesh.

What was this challenge? How did he break the idiom? Ali Khan Mahmudabad in his brilliant book Poetry of Belonging: Muslim Imaginings of India 1850-1950 puts forth an exposition that nation-states being ‘normative horizons’ subsume all other identities within them. They are ‘containers of social processes.’ Once we have put the lid of nationalism over this container, any of the multiple identities that the container has finds it hard to assert or dominate the ‘normative horizon’ of the national identity.’

Mushaira’s transformation

Mushaira itself went through a transformative phase in the early 20th century, morphing from a literary symposium into a platform for voicing politico-social-religious and identity-based issues through poetry. It became a forum that could contain multiple ‘social processes’ and legitimately challenge the ‘normative horizon’ of the nation-state. Especially, when a poet sees a nation-state being usurped by self-serving, power-grabbing politicians who often cloak themselves in patriotism to hide their nefarious activities.

The print media ‒ reportage of mushaira in newspapers, reviews in literary journals ‒ increased the physical reach of a mushaira. It was no longer just 100-200 people watching the poets in a physical space but many more, since a wider audience was tapping into mushairas through print. And the Internet further revolutionised that. Now a Rahat Indori video clip of reciting his ghazal at a Rekhta Mushaira has millions of views.

Rahat understood these intricacies. A film has to undergo censorship. A printed word in a newspaper or a literary journal undergoes editorial scrutiny. But a spoken word at a mushaira is unfettered, defying, a challenge ad infinitum negotiating the unspoken boundaries of a culture. Mushaira was the only forum where when the normative horizon is being usurped by scoundrels, the poet can challenge this hacking of the normative horizon. Rahat could play enfant terrible, as in the words of Maaz Bin Bilal, and get away wearing his politics on his sleeve. He knew he had beaten the oppressors at their own game, and he was aware that this act ‒ the wave of the hand, the glare straight into the audience, the meaningful pause before the punchline, and the all-conquering smile to wind it up ‒ of his made him hugely popular among his audiences. He became their voice.

He chose a style which was conversational, and his choice of words was of everyday usage. He knew this is his stage and his time to bare it all to his audiences. He spoke in an idiom that echoed with his audiences. To give an example Habib Jalib wrote:

Tum se pahle vo jo ik shaḳhs yahāñ taḳht-nashīñ thā

Us ko bhī apne ḳhudā hone pe itnā hī yaqīñ thā

Rahat Indori echoes the same sentiment as:

Jo aaj saahibe masnad hain kal nahin honge

Kiraaydaar hain zaati makaan thodi hai

Where Habib Jalib invokes God, Rahat invokes the tenant. Habib restricts his attack to the ownership of the throne alone, whereas Rahat extends the metaphor and in fact asserts that the people are the owners of the throne. A country where most of the urban population still doesn’t own property and lives as tenants, nothing evokes more angst than the fear of eviction. With that one line, Rahat offers a threat and a balm too – for those in power are people like us – temporary and can be evicted anytime. And what better, we’re the landlords, the owners, this time. No wonder he struck a chord with millions across the country. The final couplet of this ghazal:

Sabhi ka khoon shaamil yahan ki mitti me

Kisi ke baap ka hindustan thodi hai

Became a war cry during the anti-CAA-NRC protests recently. He became a fearless crusader for the oppressed and used his poetry and the platform of Mushaira to effectively channel the same.

Later he ventured into Hindi cinema and wrote some memorable songs like Yeh Rishta from Meenaxi, Dil Ko Hazaar Baar Roka from Murder, Neend Churayi Meri Kisne O Sanam from Ishq to name a few but he remained foremost a poet of the masses and spoke in a language that was theirs.

Is it not a wonder that he came closest to Habib Jalib, in the words of Javed Akhtar, when he took the stage and recited his poetry? And sometimes that stage was none other than the ramparts of the Red Fort, where the very people he was challenging had given their grandiose speeches.

(Danish Husain is an actor, poet and theatre director.)

✫✫✫

Remembering Rahat Indori, Fearless Poet of Dissent in Dark Times

Raza Naeem

Yaqeen kese karoon main mar chuka hoon

Magar surkhi yahi akhbar ki hai

(How do I believe that I am no more living

But this is the headline which the newspaper is giving)

I had just handed in a translation of a poem on Lebanon by the people’s poet of Pakistan, Habib Jalib, to The Wire on the evening of August 11 when social media was racked by the news that noted Urdu poet and lyricist Rahat Indori had passed away in his beloved Indore at the relatively young age of 70, just a day after being diagnosed with COVID-19 and suffering two heart attacks subsequently.

It occurred to me then that the pain of ordinary people which Jalib sought to portray in his nazms was exactly what Indori did in his ghazals in more than 50 years of service to Urdu poetry. The passing of Indori, two months after the demise of Gulzar Dehlvi (1926-2020), who was an exemplar of Delhi’s composite culture, will be especially hard for Indians given the loss of his eminent contemporaries Nida Fazli in 2016 and Anwar Jalalpuri in 2018, amidst the ongoing communalisation of national politics.

Indori was from a generation of Urdu poets boasting the likes of Gulzar Deenvi (who will be 86 on August 18), Bashir Badr, Waseem Barelvi, Javed Akhtar and Munawwar Rana. However, unlike Gulzar, Badr, Barelvi and Akhtar who received both critical and mainstream acclaim, Rana and Indori were vastly under-appreciated despite their long service to Urdu and literature.

Rahat Indori was born on January 1, 1950, in Indore. After accomplishing his initial education at home, he ascended the ladder of higher education. He obtained an MA in Urdu and then a PhD degree from Barkatullah University in Bhopal, and taught in college.

Indori, who was also a painter of no mean accomplishment, had started reciting verses in 1965 when he was just a 15-year-old. He published his first collection of poetry Dhoop (Sunlight) in 1979, followed by Rut (Season) in 1983, Mere Baad (After Me) in 1990, Panchavan Darvesh (The Fifth Darvesh) in 1992 and Kun fa Yakun (Be, And It Is) in 2002.

Later in life, in contrast to the general trend, he became a film lyricist after conquering the world of the Urdu mushaira.

Now, if one looks at the verses of Firaq, Faiz, Sardar, Makhdoom, Jan Nisar and Sahir, the common element in their poetry was the echo of revolution, but the manner of expression was very agreeable, and the tone was delicate. The audience at the mushairas used to hear them with great respect and enjoy the literary quality of their verses.

Sahir Ludhianvi would recite his long poem ‘Parchhaiyan’ (Silhouettes) for hours at mushairas without jerking his hands or feet and without any preamble or verbosity, and the audience would be quietly entertained by the poem.

Then there was the rhythm of Jigar, Majrooh and the ‘tone and rhythm’ of the so-called modulators of today. At that time (around 60 years ago), the Urdu society was alive. People used to read literature, and the audience had a deep consciousness of it. Today there is nothing like Urdu society. The mushairas are attended in great numbers by entertainment-loving individuals who would be happy with superficial verses. The audience today prefers poetry which is straightforward in tone, is emotionally expressive, rhetorical and simple. The number of people who would give anything to hear literary ideas is diminishing daily.

In this situation, it is the performance of the poet on stage, rather than the poetry, which has assumed importance. The better a poet performs, the more successful he will be. In the last 70 years, it is said that there was no better poet than Kaifi Azmi who recited in taht-ul-lafz (rhythmic speech). But Kaifi’s rhythmic recital did not come under the rubric of performance. He had his own special style, which was also important for the transmission of his revolutionary poems to the audience. In our age, Rahat Indori’s rhythmic speech was unique and made him stand apart from everyone else.

Indori was an extremely successful and popular poet of contemporary mushairas. Before his rhythm, the lamps of the best and brightest became dim. And why not, for who could understand the psychology of mushairas better than him ‒ after all, he had done a PhD on the subject of mushaira.

I have not studied Indori’s poetry with reference to mushairas. His poetry spoke about the problems of life, big and small; the political and social conditions of the present age; and the agonising hardships experienced by the common man. There was no untying of knots of some deep philosophy or any complex mystery in his poetry; however, the fact that we could listen to the heartbeats of life in it was no mean feat either.

This kind of poetry showed the true shades of night and day in the wider world. The creative use of simple and familiar words and a clear manner of expression had bestowed such a flavour to his poetry that it did not allow either the people or the cognoscenti to exit its circle of influence. Indori’s tone was sharp. His poetic temperament was marked by transparency, intrepidity and outspokenness which, in my opinion, is the quality of a true artist.

There was an abundance of protest in his poetry as well. At times, the rhythm of protest was so crude, clear and narrative in nature that it seemed to fall within the bounds of journalism at the level of ideas.

At the same time, one finds so many verses of Indori that resonate with ideas, consciousness, art and that craft and skillfulness which make a verse into a masterpiece. I have no fear in saying that it is these verses that will serve as a reference to his literary identity, apart from the commercial action of ‘mushaira games’. The future too will search Indori with the same reference.

The vocabulary Indori used to describe the savage realities of our time was equally harsh. He had a distinctive position as an emerging ghazal poet after the partition of India in 1947. Indeed, as one of midnight’s children, the following verse of his spoke for the circumstances and feelings of those who migrated to Pakistan, creating quite a stir when he recited it decades later in Karachi:

Ab ke jo faisla hoga voh yaheen par hoga

Hum se ab doosri hijrat nahi hone vali

(This very place will now be the one for the final decision

We will be unable to make another migration)

Indori was not a poet of the Progressive Writers Movement, but he was progressive. He was not a modern poet either, but he was modern as far as themes and ideas were concerned. He was that important poet of our age whose poetry did not need to be associated with any movement; rather, many movements decorated their flags by using his verses as slogans.

Most recently, when nationwide protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, galvanised the whole of India late last year, these verses from his ghazal, Agar khilaaf hain to hone do (If they are against, let them be) became viral:

Jo aaj sahib-e-masnad hain, kal naheen honge

Kirayedaar hain, zaati makan thodi hai

Sabhi ka khoon hai shaamil yahaan ki mitti mein

Kisi ke baap ka Hindustan thodi hai

(They will not remain, those who today sit on the throne

They are renters, they do not own this home

The blood of everyone mixes with the soil here

Hindustan is not anyone’s personal property, how can they dare)

Indori’s poetry had two foundations: one was his feelings and the other was the individualistic colour of his ideas. He was a poet who expressed the collective pain of people living in a time of venal and oppressive politics. In short, the starkness of the present time became an abiding theme with him. His ghazal changed its mood and freed itself of love and romance:

Bethe hue hain qeemti sofon pe bhediye

Jangal ke log shahr men abaad ho gaye

(Wolves sit on costly sofas

The people of the jungle have come to populate the cities)

The reality that this verse alludes to is right in front of us, it has become so much a part of our lives that it is virtually invisible. With the magic of merely four words, namely sofas, wolf, jungle and city, Indori successfully pointed to the class struggle, human exploitation and the defects of capitalism. Had this verse reached us from the pen of Sardar Jafri or Kaifi Azmi, we would have made ourselves deaf beating the drums of Progressivism and would have deemed the rebirth of the 80-year old Progressive Writers Movement.

In the same manner, Indori wrote:

Riwayaton ka tahaffuz bhi inke zimme hai

Jo masjidon main safari pehen ke aate hain

(The protection of traditions too is their responsibility

Who come to the mosques dressed in a safari)

However, I do not consider staying stationary in a fast-paced world to be the equivalent of old trees, ruins and milestones ‒ this imitation is death, not life. To wear a short pyjama and long kurta, meaning widening the ankles and conducting the imamat (leading the prayer) by wearing a kurta coming below the knees is no longer necessary. These very requisites have damaged Islam. It is my claim that if the conditions of ablution (vuzu), cap (topi) and bookstand (rahl) for the recitation of the Koran are done away with, the numbers of reciters will suddenly increase.

And again:

Voh paanch vaqt ka namazi nazar aata hai namazon main

Magar suna hai ke shab ko jua chalata hai

(He appears to be very devout in his prayer

But I hear that in the evening he becomes a gambler)

But then Indori also wrote:

Yahi purane khandahar hain hamari tehzeeben

Yaheen pe boorhe kabootar hain aur yaheen shahbaz

(Our cultures are these same old ruins

Here too are the aged pigeons and the falcons)

Had just this single couplet of Indori become famous, his place in the history of our poetry would have been preserved. It could only have been written by a poet who was aware of the history and psychology of the rise and fall of nations, who knew full well that decline never comes from without but is created from within. He did not lament over the past but had the foresight to understand the past.

Yet it is also a sad truth of our times that while Indori practically reigned over the mushaira, critics and editors of literary magazines studiously ignored him because he was neither beholden to an ideological camp nor any dominant literary lobby. Some literary mandarins demeaned his popular appeal by labelling him a ‘poet of moments and mushairas’ rather than a highbrow poet of high literary culture. And poets much lesser than Indori were honoured and appreciated with awards and recognition at the state level.

Indeed, it is ironic that among the first to condole Indori’s passing were his contemporaries Gulzar and Javed Akhtar, two of the most decorated and honoured Urdu poets in India today. Rahat Indori’s response to his critics’ charge would have been that he had already received his reward by being present in the public imagination.

A friend wondered aloud on Facebook whether Rahat Indori was the last of the great dissenting poets and seemed to think that the line which had begun with Josh through Faiz to Jalib had now reached an end. Indori had answered this question about two decades ago in an interview with Haseeb Soz in his luminously idealistic manner: “Such fresh voices too arrive sometimes from mushairas which sharpen the light of hope and one guesses that this sequence [of poets coming and going], which has been carrying on for the last 150-200 years, will not end; in fact, new people will keep joining this caravan with new fragrance and new light.”

As I conclude these lines on the day of Krishna Janmashtami, perhaps the best tribute to this crusader for communal harmony, composite culture and people’s poetry would be to pay heed to his words:

Jin charaghon se taasub ka dhuaan uthta hai

In charaghon ko bujha do toh ujale honge

(The lamps from which rises the smoke of prejudice

Extinguish them to create light and justice)

[Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. All translations from Urdu are by the author.]