(Published on the occasion of Mahatma Jotiba Phule’s birth anniversary on April 11.)

Phule was born in a Shudra family in Pune on April 11, 1827. He was one of the most radical activist-thinkers of the 19th century who waged a relentless battle against Brahmin hegemony and Brahmins’ religion, fought against the oppression of Shudras (lowest Varna in the Varna hierarchy of the Brahmins’ religion), Ati-Shudras (now known as Dalits) and women, and strived for an egalitarian society based on truth and reason. Phule married Savitribai Phule, a revolutionary figure in her own right, in 1840 and the couple worked alongside each other till Jotiba’s death in 1890.

Support to women’s causes

Jotiba Phule was a vocal supporter of women’s education, widow remarriage and women’s right to divorce, and a staunch critic of anti-women traditions like widow tonsure, child marriage and polygamy.

Phule started a school for girls in Pune in 1848 which was open to girls from all castes. It was the first school for girls started by an Indian person. Phule played a key role in starting educational institutions like “Native Female School, Pune” and “The Society for Promoting the Education of Mahars, Mangs and Etceteras” in the 1850s. Phule himself taught in these schools, as did Savitribai.

Brahmin teachers in their private tuitions would teach Sanskrit mantras and slokas, Puranic mythology, ideas of Varnashrama Dharma, etc., to their students. Phule made sure there was no Brahminical indoctrination in his schools and included topics like language, grammar, maths, history, geography, physics, chemistry and agricultural science in the syllabus. The quality of education imparted in Phule’s schools can be gauged by an essay written by a 14-year-old Dalit student Mukta Salve. Salve minced no words in attacking the Peshwas, the Brahmins and the Brahmins’ religion. She wrote, “If the Vedas belong only to the brahmans, then it is an open secret that we do not have the Book. We are without the Book—we are without any religion. If the Vedas are for the brahmans only, then we are not bound to act according to the Vedas. If merely looking at the Vedas can get us into grievous sins (as the brahmans claim), then would not following them be the height of foolishness?”

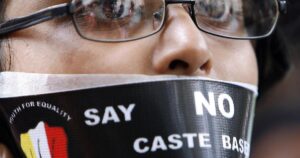

It is no secret that Brahmins had restricted the knowledge of Sanskrit and Sanskrit literary tradition to themselves. They also held a hegemony over administrative jobs in the royalty. When the British started modern education in India and started recruiting Indians in administrative jobs, Brahmins, unsurprisingly, established their hegemony in these jobs. Moreover, they dissuaded others from taking up education and tried to block the British government’s efforts to open up education so that they would not face competition from non-Brahmins.

Phule himself was taken out of school when a Brahmin clerk took issue with the fact that a Shudra child was taking education. He later completed his education in a Scottish missionary school. Against this background, one can understand how radical Phule’s act was to enrol not just Shudra-Atishusra boys but also Shudra-Atishudra girls to his schools. Phule faced immense backlash for going against the Brahminical social order that encouraged only Brahmin men’s education, and Phule’s father was forced to kick him out of his house.

In 1863, Pune witnessed a horrific incident. A Brahmin widow named Kashibai got pregnant and her attempts at abortion didn’t succeed. She killed the baby after giving it birth and threw it in a well, but her act came to light. She had to face punishment and was sentenced to jail. This incident greatly upset Phule and hence, along with his longtime friend Sadashiv Ballal Govande and Savitribai, he started an infanticide prevention centre. Pamphlets were stuck around Pune advertising the centre in the following words: “Widows, come here and deliver your baby safely and secretly. It is up to your discretion whether you want to keep the baby in the centre or take it with you. This orphanage will take care of the children [left behind].” The Phule couple ran the infanticide prevention centre till the mid-1880s.

Satyashodhak marriage

Phule was well acquainted with many Brahmin social reformers in Pune, such as Mahadev Govind Ranade, but didn’t have anything to do with their reformist agenda. He kept an arm’s distance from organisations like Pune Sarvajanik Sabha and Prarthana Samaj because he considered them as operating within the framework of Brahminism. He felt the need to start an organisation that would challenge Brahmins’ religion and their trickery head-on. Thus Satyashodhak Samaj was born on September 24, 1873, lighting the flame of the non-Brahmin movement in Western India.

One of the key initiatives of Satyashodhak Samaj was Satyashodhak marriage. This marriage was supposed to take place without the Brahmin priest and the Brahminical rituals. In weddings ordained by Brahmin priests, the priest sings the verses while the guests bless the couple by throwing rice grains on them. Phule wrote alternative verses to replace the traditional ones and infused them with egalitarian content. These verses were supposed to be sung by the bride and groom themselves and prodded the groom to take cognizance of women’s oppression and work for women’s rights. Afterwards, the couple had to take a common vow. Satyashodhak marriages avoided show and pomp generally associated with Brahminical weddings.

The first Satyashodhak marriage took place on December 25, 1873, between Sitaram Jabaji Alhat and Radha Nimbankar. Savitribai shouldered the expenses for this wedding. Though the number is minuscule, Satyashodhak marriages take place even now in parts of Maharashtra.

Satyashodhak marriages were radical on at least one count. By refusing to allow Brahmin priests to preside over the ceremony, they sought to divest Brahmins of their sacrality and undermine their religious authority. Brahmins probably understood what symbolic threat this posed to their authority in all spheres of a non-Brahmin’s life (birth, marriage, death, various pujas, etc) and that is why there were a number of litigations against not employing Brahmin priests in weddings on the grounds that this act robbed Brahmins of their earnings.

Satyashodhak marriages can be considered as a precursor to Periyar’s concept of self-respect (Suyamariyathai) marriage. A marriage based on love, respect and equality between partners, one that doesn’t bind itself in sectarian identities like caste, and one that directly challenges Brahminical traditions and Brahmins’ religious authority are features common to both Satyashodhak marriages and self-respect marriages.

Personal is political

Phule spoke passionately against the oppression of Shudras, Ati-Shudras and women but he also practised what he preached. Even after living together for many years, Jotiba and Savitribai Phule didn’t have a child. So Jotiba Phule’s relatives, colleagues and friends advised him to get married the second time but he categorically refused. If the fault lies with the man and not the woman, this society doesn’t permit the woman to marry another man. Men routinely engage in bigamy and polygamy but will it be okay with men if women married other men and brought them to the house? This was the reasoning given by Phule. In 1873, Phules adopted the son of a Brahmin widow who had come to their infanticide prevention centre for delivery. They named him Yashwant.

Phule was an epoch-maker. His contemporaries at the most advocated reforms within the prevalent cultural framework, while Phule dared to challenge the cultural framework itself. Since his politics was rooted in principles of truth, reason and equality, it naturally led him to question the hold of Brahminism over the Shudras, Ati-Shudras and women. Gail Omvedt said of Phule, “In regard to issue of women’s liberation, Phule is one of the very few social reformers in history who deserve a woman’s respect.” Phule strove all his life to free people from the shackles of Brahminism and this reflects in his words and actions—in public as well as private life.

(Note by author: This article largely draws on Shriram Gundekar’s book ‘Maharashtrache Shilpkar: Mahatma Jotiba Phule’ for biographical details about Phule. Article courtesy: Newslaundry.)