For what I had to say, in aesthetics, in the performing arts, as well as what I had to say socially, politically – the medium was not the cinema, it was the theatre.

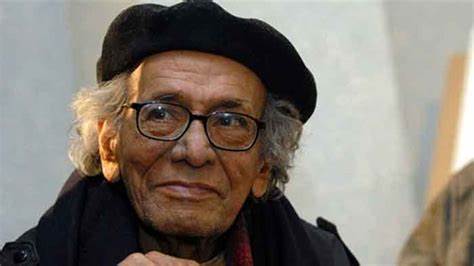

– Habib Tanvir

Born on September 1, 1923, Habib Tanvir would have been 100 years old today. He was 86 when he died in 2009. His association with the stage remained intact until his death, spanning nearly three-quarters of his life. In the course of his long innings in theatre, the playwright-director did not only evolve a new style and idiom for his own work; he also, in some ways, redefined the very concept of modernity, particularly in relation to culture.

Although Tanvir had seen and participated in stage plays during his school days in Raipur, it was in the 1940s in Bombay that he came to be seriously involved in theatre when he joined the local chapter of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). His journey in theatre brought forth a large and richly varied corpus of plays, which includes original texts as well as adaptations of Sanskrit and Elizabethan classics, Moliere, Zweig, Brecht, and Tagore.

How Tanvir got to Bombay is an interesting story in itself. He was in his early 20s, pursuing his studies at Aligarh Muslim University for a Master’s degree. Half way through it he decided to change course and, instead, explore the possibility of a career in cinema. This required him to travel to Bombay. Since he did not have the money to pay for the train ticket, he applied for recruitment in the Royal Indian Navy which offered a return fare to enable applicants to travel to Bombay for preliminary interviews!

Obviously, Tanvir didn’t make it to the navy. Nor did he want to. But he was in Bombay now and that was what he had actually desired.

In the whirl of Bombay’s left-wing politics

Those were politically surcharged days. The environment was throbbing with revolutionary activism and Bombay was one of its major centres. In due course, the young Tanvir was also drawn to leftwing politics and became actively involved in its cultural movement which was led by the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) and IPTA.

His association with these organisations brought him in contact with stalwarts like Ali Sardar Jafri, Sajjad Zahir, and Shaukat and Kaifi Azmi as well as Balraj Sahni, Dina Pathak, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, and Zohra Sehgal. These relationships helped him grow artistically and politically. It would not be wrong to say that Bombay was the crucible in which Tanvir’s social and cultural consciousness was tempered.

Tanvir used to tell of an interesting incident relating to his work with IPTA. Once, Balraj Sahni was directing a play in which Tanvir had a role and was required to shed tears in one scene. Balraj Sahni put him through the scene repeatedly but could not get him to perform the act convincingly. In the end, Balraj Sahni slapped him so hard on the face that Tanvir’s eyes filled with tears. Sahni looked at him and, smiling, remarked: “Good. This is what is called muscle memory. Now you will never forget it.”

When the left movement weakened and IPTA virtually became dysfunctional, Tanvir left Bombay and moved to Delhi in 1954. The reason that he cited for this move is that he wanted to get out of the way of the temptation to act in films:

Because by then I had come to the conclusion that in the cinema of those days there was no autonomy for the artist – you could not act the way you wanted, nor direct the way you wanted. The producer, who had no artistic sense, who was only a money bag, a financier, would meddle in the work of the director, actor, writer, everyone… Anyhow, right or wrong, I was convinced that I had something to say. And for what I had to say, in aesthetics, in the performing arts, as well as what I had to say socially, politically – the medium was not the cinema, it was the theatre. This was a very clear realisation in the early fifties which brought me to Delhi.

A new ‘stage’ of life

In Delhi, Tanvir began with school children, writing and staging plays for and with them, before producing the first embryonic version of his celebrated play Agra Bazar. First staged in the Okhla campus of Jamia Millia Islamia, with teachers, students and residents of Okhla village in the cast, the play was part of the Nazir Day events organised by the Jamia chapter of PWA. It dramatised the work, life and times of an unusual 18th century Urdu poet, Nazir Akbarabadi. The production, although still in an early stage, not only marked Tanvir’s permanent relocation to Delhi but also his debut as a playwright-director on the theatre scene.

A year later, in 1955, he went to England for theatre training and travelled extensively through Europe, watching plays and meeting directors and actors. He even travelled to Berlin with the express purpose of meeting the great German director, Bertolt Brecht. Although the meeting failed to materialise – Brecht died in Berlin in August 1956 – Tanvir spent nearly eight months watching the performances at the Berliner Ensemble, sitting in on their rehearsals, and discussing the productions and Brecht’s theatre practice with artists like Helene Weigel and Elizabeth Hauptmann. He saw the practical examples of Brecht’s “epic” theory which offered a radical alternative to the artistic and social restrictions of the dominant individualist forms of middle-class drama.

Quest for a new theatrical idiom: the birth of Naya Theatre

Tanvir spent several years researching and studying folk traditions in drama, story-telling, music, and dance. He frequently wandered through the interiors of Chhattisgarh, living with and talking to local groups and individual performers .

After several long years of sustained, single-minded pursuit through exploration and experimentation, he eventually arrived at a theatre where he worked almost exclusively with village actors who brought with them their traditional style of acting. His productions not only used traditional performers but also made abundant use of folk music and musicians and, frequently, of folkloric narrative material. The language of his plays, too, became in large part the folk speech. In short, his plays were created in remarkably close proximity to the traditions of folk performance in India in general and in Chhattisgarh in particular.

Tanvir always emphasised that the most important thing that he learnt from his European experience was that meaningful theatre was possible only if one built close to the traditions of one’s people. This was also the lesson he had learnt from his IPTA days.

So, on returning to India, he began to actively explore the possibility of creating such a theatre. He began by including six village artists from Chhattisgarh in his first production after returning from Europe: Sudraka’s Sanskrit classic, Mritchchakatikam (translated into Hindustani as ‘Mitti ki Gaadi’). This was his first and limited engagement with the folk performers.

Some years later, it developed into a full-fledged partnership between Tanvir’s educated, formally trained consciousness and the natural talent and skills of his village artists. This partnership was what defined his repertory company, Naya Theatre, and set it apart from all other drama groups of the time.

It was in 1959 that Tanvir and Moneeka Mishra, his partner in life and theatre, founded Naya Theatre. Funding being scarce, sustaining the theatre company was difficult. There was also the struggle for livelihood which obliged them to take up various other assignments.

Success came in 1970 in the form of a Sangeet Natak Akademi award, with the institution commissioning a large number of performances of Agra Bazar in several cities from Delhi to Srinagar. It enabled Tanvir to bring back his performers. There was no stopping him from taking Naya Theatre to new heights.

He did not accomplish this journey by himself. Besides Moneeka, whose companionship and assistance was a crucial source of strength for him, a long line of superb Chhattisgarhi performers were equal partners in the journey, lending it a brilliance rarely seen on Indian stage. Thakurdas, Madan Lal, Lalu Ram, Bhulwa Yadave, Brij Lal, Udayram Srivas, Devi Lal Nag, Fida Bai, Mala Bai, Ramcharan Nirmalkar, Ravi Lal, Agesh Nag, Govind Lal Nirmalkar, Deepak Tiwari, Poonam Tiwari, Chait Ram Yadav – what a vibrant galaxy of stage actors!

Sadly, except for a few (Ravi, Agesh, and Poonam) no other artiste from this group of memorable artistes survives today. But those of us who saw them on stage still have their faces and the mesmerising power of their acting vividly etched in our memory.

It was this partnership that lay behind those memorable masterpieces—Agra Bazaar, Mitti ki Gadi, Charandas Chor, Bahadur Kalarin, Lala Shohrat Rai, Shajapur ki Shantibai, Hirma ki Amar Kahani, Kamdeo ka Apna Basant Ritu ka Sapna, Dekh Rahe Hain Nain, and Raj-Rakt. Some of these are regarded today as classics of contemporary Indian theatre.

Further, Tanvir’s social consciousness, tempered in the crucible of radical politics, never left him. Works like Ponga Pandit, Zehreli Hawa, Sadak, Kushtia ka Chaprasi and even the controversial Indira Loksabha are examples of how Tanvir used his art as a weapon to intervene in some immediate socio-political situation or movement.

An idiom without parallel in India

The theatre that Tanvir created was unique and, to the best of my knowledge, had no precedent or parallel anywhere in India. It eluded categorisation. Scholars and critics tried to explain it variously – in terms of the Indian folk tradition, or as an example of the Brechtian epic theatre, or, sometimes, even in terms of the aesthetics of Natya Shastra.

The fact, however, is that, while Tanvir’s work, in its different aspects, might have showed an affinity with them, it did not follow any of them consciously or in its entirety. They came into his work through his village actors and their background in traditional folk performances.

This folk legacy was a cornerstone of Tanvir’s theatre practice. It could be evidenced even in those aspects which are reminiscent of the Brechtian style and technique. For example, Tanvir’s actors demonstrated or “showed”, rather than became emotionally one with the roles they were playing. This is similar to the epic style that Brecht recommends in which an actor ‘performs’ rather than ‘lives’ (as in Stanislavski) the role. But it came into Tanvir’s theatre not as a conscious imitation of Brecht’s theory but rather as part of the repertoire of skills that the folk actor had inherited from tradition.

This is not surprising because, in developing his theory and practice of epic theatre, Brecht too had drawn upon the collectivist or communitarian traditions of pre-bourgeois origins. The only feature that suggests some degree of a conscious Brechtian influence is the use of songs to comment or elucidate an action or situation and not as autonomous musical interludes as in the folk dramatic tradition.

‘I have never run after folk forms, only after folk actors’

This writer has had the privilege of watching almost all of Tanvir’s productions and seeing his actors on and off stage. Drawn from the folk performance tradition of Chhattisgarh called nacha they were mostly unschooled and had no formal or informal experience of the modern stage. Working with an urban, professional repertory company was an absolutely new experience for them.

But, once they got used to it, they were incredible. I do not know of any other theatre group in India which can boast of such a roll call of unforgettable performers.

Take Fida Bai who, when Tanvir first noticed her during a month long nacha workshop in Raipur in 1972, had no stage experience other than singing and dancing. But she turned out to be one of the most powerful female stage actors of post-Independence India.

Fida came from a Dalit background and was completely illiterate. She could not even sign her name. She had begun her career as a nacha artiste. Like other Naya Theatre artistes coming from the Chhattisgarhi folk theatre background, she was versatile. She could sing and dance as well as act.

With her remarkable stage presence, booming voice, and histrionic skills, she made every role she played unforgettable. Her performances as the queen in Charandas Chor and in the title roles in Bahadur Kalarin and Shajapur ki Shantibai (an adaptation of Brecht’s Good Person) are remembered to this day. Sadly, she retired from the stage too soon because, after a tragic incident, she lost her voice and could no longer perform.

Intertwined strands of traditional and modern

And yet, for all its involvement with traditional music, actors, and styles of performance, the theatre that Tanvir developed was not a variety of ‘folk theatre’.

Undoubtedly, in his theatre, bodies, voices, movements and gestures, skills and rhythm, music and speech – all these belonged to the folk performers. But, on a deeper level, the practical aspects of staging and critical consciousness (characterised by complexity of vision, subtlety and irony in articulation, and contemporaneity of concerns) which gave them direction and form came from Tanvir’s modern disposition.

In other words, his plays were strongly evocative of folk performance but without ever pretending to be actually it. Rather, they were examples of a theatre which was simultaneously modern and traditional.

However, these two dimensions of Tanvir’s work are not two separate currents or aspects of his theatre. On the contrary, they are closely intertwined and defining strands in the vibrant artistic tapestry of his work. He combined and interwove them into a style of theatre which was unique in the sense that it neither followed the European model nor did it blindly copy any traditional Indian form.

As for the forms of folk culture, Tanvir’s approach to them was neither revivalist nor antiquarian. He did not romanticise or sentimentalise them. He knew quite well the debasement that the traditional forms had suffered due to rapid urbanisation and the homogenising influence of films and TV. He was also aware of the severe ideological limitations underlying the simple approach to issues and problems that one found in traditional forms or folk culture.

However, this did not prevent him from recognising that there were skills and energies that still existed in Indian folk traditions which could be drawn upon to forge a new, truly indigenous performance idiom. So, what he did was to bring in these energies and strengths of traditional performances in order to fashion an artistically exciting and cognitively enriching theatre which was specifically contemporary or non-traditional in both its outlook and its form.

Hence, the statement earlier on in this article that in forging his unique idiom, Tanvir was also, in some ways, redefining the very concept of modernity, particularly in relation to culture. He had grave reservations about the post-colonial project of modernity which tended to exclude from the focus of its attention large areas and large sections of ordinary Indians who lived outside metropolitan centres.

This modernity, Tanvir recognised, was flawed. It failed to give adequate attention or importance to India’s many languages, cultural forms, traditions, and lifestyles. In the name of nation and nationality, markers of regional identities were often swept under the carpet and even sought to be bulldozed into one homogenous entity by establishing large, monolithic, centralised policies and “national” institutions for the implementation of those policies.

However, Tanvir did not reject modernity per se. At the same time, he cherished a rational and scientific approach and a historical perspective on life and issues. What Tanvir’s work implied was, on the one hand, a more sensitive and more imaginative approach to traditions and, on the other, a more inclusive, just and equitable concept of modernity. It is this complex blend, this mutually enriching partnership, of tradition and modernity, that defines Tanvir’s theatre and gives form to his plays.

While the connection between Tanvir’s work and folk theatre traditions, particularly Chhattisgarh’s nacha, is widely recognised, what is not fully appreciated is his distinctive approach to the “folk” as well as the “modern” which clearly set him apart from his contemporaries and made his work so memorable.

(Javed Malick is an academic and well-known theatre scholar. Courtesy: The Wire.)