Gauri Speaks in 2020

Githa Hariharan

On September 5th, 2017, Gauri Lankesh was assassinated in her home in Bengaluru. Why? The only possible answer seems to be this: she was shot because she did her job well –whether as a journalist or as an activist. Gauri worked hard at being a voice of reason. She insisted on being a voice of dissent. When she saw injustice and inequality, she insisted on speaking up; doing something about it. And for this she was brutally silenced – just as other rationalists, scholars and activists were before her. Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare, MM Kalburgi. Then Gauri Lankesh. May we never forget these names. May we never forget what these people did, and what they stood for.

Actually, there is no danger that will happen. For two reasons, one bad, one good.

Three years later, in 2020, the times remain the same. To be honest, they seem worse.

Consider the clamping down of all opposition. Consider 2018. January 1, 2018 marked the bicentennial of the Battle of Bhima Koregaon, a powerful symbol of dignity for the dalit community, as well as a rallying call. A large event was planned; the convenors of the event were the respected retired Judges from Pune, BG Kolse-Patil and PB Sawant. They had organised public events before, whether against communalism or in defence of the Constitution. This time, they decided that they would call the event Elgar Parishad. The word elgar was apposite for the moment. It means a declaration made aloud. And the “declaration” the organisers had in mind was a response to the increasing violence from Hindutva groups, especially the “cow vigilantes”. This was the response: Fight communal forces. This was the declaration: The right-wing forces do not accept the Constitution. They do not believe in the democracy it promises; or the socialism it hopes to build, or the secularism it rests on. And this was the elgar that rallied citizens around the foundation of the Indian republic: Save the Constitution. Save the Indian people.

The Sangh brigade was also at the event, not to save the Constitution, but to attack it – by attacking the citizens the Constitution protects. The story changed shape. It became a malignant fiction imagined by the Pune police. “Rebellious thoughts’ and revolutionary speeches had led to the violence. In case this did not seem weighty enough, a conspiracy to assassinate the Prime Minister was added as a footnote. Poets, scholars, lawyers — human rights activists all — were hounded; their homes searched; their books and computers and phones examined for those “rebellious thoughts”, usually personified by a “link with Maoists”.

We have yet another list of names we live with now. Poet Varavara Rao; “people’s lawyer” Sudha Bharadwaj; other scholars and writers and activists who serve as cruel examples, warning each one of us to keep silent: Don’t criticise the government. Don’t question Hindutva. Don’t talk about people’s rights.

In 2019, the election results emboldened the Hindu supremacists to go all out. One after the other came the assaults on the already torn promises made to the Kashmiri people – Article 370 was abrogated, statehood taken away.

Plans were afoot to conduct an all-India National Register of Citizens despite the terrible costs of the NRC exercise in Assam.

Then came the Citizenship Amendment Bill, passed as the Citizenship Amendment Act or CAA. The CAA has changed, fundamentally, the notion of citizenship by linking it with religion. It has changed the Citizenship Act 1955 to expedite the process of naturalisation for non-Muslim “minorities” from Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan: “Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians”. The exclusion of Muslims is not innocuous; it holds, like a sword over every Muslim’s head, the possibility of being diminished to the second-class citizen Golwalkar had imagined. And this implicit threat has to be seen side by side with the plan to extend the NRC across India. Altogether, every move of the Hindu supremacists since the elections in April 2019 has taken one more step toward excluding more and more of our citizens from the contract between them and the state.

Meanwhile, the crushing of all dissent – all freedom of speech – continues. The list grows, stretches, rolls forward, from Sudha Bharadwaj and Varavara Rao to Anand Teltumbde and Gautam Navlakha.

In 2017, Anand Teltumbde had said of Gauri and her newspaper: “Lankesh Patrike was a platform for the oppressed and all marginalised sections of the society including dalits and women; and pioneered a brand of journalism that became an inspiration to many others. It became a mouthpiece for many progressive movements such as “Raitara Chaluvali” (farmers’ agitation), Dalit movement, and Gokak movement.”

In other words, this is what journalists must do. This is what citizens, engaged citizens, do.

And for believing this, for practising this, Anand Teltumbde too has gone to jail. Along with other activists, he remains incarcerated. Our list of political prisoners grows, though the “evidence” against them reeks of fabrication; though there is no talk of a trial; though many of them are old and ill; though Covid stalks the prisons.

Is all lost then? Is the narrative completely dark, do we have nothing but bad news for Gauri?

Of course not.

Since 2017, there have been many scenes of resistance we could show Gauri, on campuses with the young people she loved so much; in the courts; online; on the streets. 2018: how Gauri would have loved the sight of farmers marching, filling up roads and maidans, making their way from villages to cities, and reminding corporate Mumbai and governing Delhi who feeds them all!

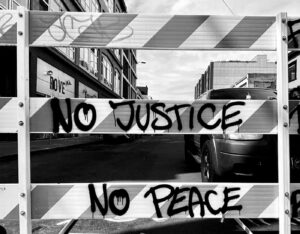

And there was more to come in 2019, much more. People we had not met before, young students and old grandmothers, led us in speech and slogan and song. How Gauri would have participated with every bone and muscle in her body in the anti-CAA protests that let the people’s voices, women’s voices, be heard everywhere in this country! Marches, art on the streets, women and children on the streets; the tricolour and the Constitution taken back by the people. People saying No to NRC with poetry: “Hum kaagaz nahin dhikayenge!” People taking back their India: “Kisi ke baap ka Hindustan thodi hai…” And people promising each other and themselves – and the Hindu supremacists: We are here, we are watching. Hum Dekhenge. Naam paarpome. Navu Nodonna.

Gauri Lankesh performed her duties as a journalist and a citizen with uncompromising honesty. She was guided by democratic, secular values that insist on an India in which speaking up against division and hatred is every citizen’s right. In 2020, despite horrific violence, despite the avalanche of attacks on diversity, on Muslims, on dalits and adivasis, on women – on equality – we still have voices that speak up. Voices that speak up despite the threat of NIA, UAPA, sedition charges, hounding, trolling. With Covid-19, since March 2020, the powers that be must have hoped that voices could be muted more efficiently. But people are finding new ways to make themselves heard. On the day Prashant Bhushan’s contempt case was heard in court, people made their presence felt, even if it was online. And now, in the run-up to Gauri’s death anniversary, over 70 organisations have endorsed a call from PUCL for a Protest Week from August 28 to September 5. August 28 marks two years since several human rights activists were arrested in the Bhima Koregaon conspiracy case. September 5 marks three years since Gauri was silenced with a bullet.

If we speak, Gauri will continue to speak.

In 2017, when Gauri was assassinated, writer Boluwaru Mohammad Kunhi said to her: “Everyone is with you now, wherever you are. Think that, just as you thought when you were with us.”

If we speak, Gauri will continue to speak through us. Our voices will come together as they should, strengthen our practice of democracy. Which is why once again, in September 2020, we pledge to continue Gauri’s fight against the haters of free speech and a plural India. We will continue to speak on her behalf and ours. They cannot silence us all.

(Githa Hariharan is an Indian writer based in New Delhi. The article was originally published in the Gauri Lankesh News.)

❈ ❈ ❈

Remembering Gauri Lankesh: Adamant Ideologue to Some, Akka to the Underprivileged

Rajendra Chenni

She was such a diminutive person that most of us would see her as a “Gubbachchi”, a Kannada word which translates to little sparrow, or the little one of a sparrow. The translation does not do justice, as it does not communicate the love, affection and the protective feeling which accompanies this term of endearment in Kannada.

When she was shot dead, and lay crumpled in a pool of blood, she was still a gubbachchi; beyond all the shock and sorrow we were also left wondering who could pump bullets into the tiny body of this gubbachchi. For older people like me, who had seen the miracle and metamorphosis of the little sparrow into a feared, hated political being, it was still a surprise that hyper-masculinist nationalist forces were so disturbed by her, they decided to physically eliminate her.

I had met her with K.S. Vimala, who is also a fierce, committed activist in Bengaluru as Ganesh Devi and some others, including me, came out of the chief minister’s residence. We had taken a delegation to the CM to request him to expedite the enquiry into the murder of Prof. M.M. Kalaburgi on August 30, 2015 in Dharwad. Gauri and Vimala were to be a part of the delegation. However, confusion between the two offices of the CM (Krishna and Kaveri) had the two of them running to meet us as soon as we came out.

We requested her and Vimala to see the CM again to pursue the matter.

When I asked her if anything was being done about the Baba Budangiri controversy, she pointed to her worn-out slippers and said: “See, I have worn out my footwear pursuing it” (a common idiom in Kannada). We all left the place. Exactly a week later, she was shot dead.

I had vaguely heard about her when I had come to Shivamogga in 1980. Just a couple of years later, her father, the great Kannada writer P. Lankesh, had launched ‘Lankesh Patrike‘ – a tabloid which proved to be the most important phenomenon in Karnataka society in the second half of the twentieth century. At the height of its popularity, Lankesh had visited Shivamogga and we, the admiring crowd, took him to a girls’ junior college to talk to the students. Lankesh looked at the students and said, ‘Oh, these little girls, just like our Baby and Gouru. Baby was Kavitha Lankesh and Gouru was Gauri Lankesh. Nearly four decades later, his voice and words remind me how Gauri’s father loved her. Of course, like all children, she took her time, not only to acknowledge her legacy, but carry it forward.

After a long interval we met again, late one evening, in a badly-lit, dingy, small room in a college in Shivamogga. In the room, which belonged to Dalit leader Prof. Rachappa, we founded ‘Komu Souharda Vedike‘ (Communal Harmony Forum), which went on to lead the struggle to protect Baba Budangiri Shrine in Chikkamagaluru. For centuries, the shrine had been a sacred place symbolising a syncretic faith which was especially followed by poor Hindus and Muslims. The BJP had declared that it would turn it into another Gujarat and another Babri Masjid. None of us thought the small meeting would lead to a powerful movement against communalism. It was not because of us, but because the entire state rose up to protect the plural tradition of Karnataka.

Gauri, who had not yet fully left her ‘English Journalist’ phase behind, attended some of our preparatory meetings. I was still sceptical about her. But, by the third annual meeting at Chikkamagaluru, she had not only joined the movement, but had the audacity to invite me to “our” meeting! We loved her for her dedication and a total immersion into what she set out to do. From then on, she made it her mission and became the most strident voice against Hindutva forces. ‘Gauri Lankesh Patrike’ became the most powerful platform for communal harmony. She supported the extreme left and earned the title of a ‘naxalite journalist’.

But by then, her transformation had been amazing. Though she spoke like an adamant ideologue, she became akka (sister) to practically all who were unprivileged. Harassed by a hundred legal cases, trolled by the right-wing 24X7, with little money to support her tabloid, Gauri was always an ebullient, perky, little packet of energy.

Many of us had not realised how Gauri had become an integral part of the Kannada imagination. She had become a symbol of empathy, succour and support for thousands. When we saw an ocean of young faces, all declaring “I am Gauri” when we gathered at Bengaluru to protest her killing, we understood that the Gubbachchi had metamorphosed into a tidal force of democracy and dissent. We old men are such tardy learners.

(Rajendra Chenni is an academic, writer and the Director at Manasa Centre for Cultural Studies, Shivamogga. He has been involved in several movements for communal harmony. Article courtesy: India Cultural Forum.)