[Note: This article is being published to commemorate the death anniversary of Dadabhai Naoroji on June 30.]

“Let us always remember that we are all children of our mother country. Indeed, I have never worked in any other spirit than that I am an Indian, and owe duty to my country and all my countrymen. Whether I am a Hindu, a Muslim, a Parsi, a Christian or any other creed, I am above all an Indian. Our country is India, our nationality is Indian.”

These inspiring words were spoken by Dadabhai Naoroji in Lahore, where he was presiding over a session of the Indian National Congress for the second time. Earlier, he was president of the Congress at its second session in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1886 and, later, for the third time in Calcutta again in 1906.

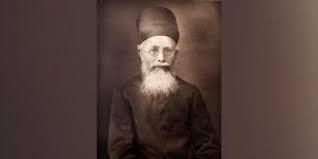

Naoroji was born in Bombay (now Mumbai) on September 4, 1825 in a priestly Parsi family, the only child of Manekbai and Naoroji Palanji Dordi, who had migrated from Navsari in present-day Gujarat.

A brilliant student, Naoroji joined the famed Elphinstone College, Bombay after passing the matriculation examination and graduated from there in 1845, winning many prizes and scholarships. On the completion of his college career, he was appointed assistant professor at Elphinstone College and awarded the honorary LLD degree by Bombay University.

As a devout Zoroastrian, Naoroji learnt that one should be pure in thought, speech and action. He also read the lives of many great men of world history, which inspired him to think that he owed a debt to society. He decided to pay back the debt by devoting himself to the service of the people.

Naoroji looked beyond his profession of teaching and felt the need for reform in society. He started schools to impart education to women and societies to provide young people with opportunities to discuss various literary, scientific and social subjects.

He also began a Gujarati weekly named Rast Goftar (‘Truth Teller’) to spread his ideas in the city of Mumbai, where he became famous as a pioneer of social reform and was regarded as “the promise of India” by his fellow professors.

In 1855, Naoroji went to England to work as a partner in a commercial firm named Cama & Company. This was the first Indian firm to be founded in London. But his principles of putting ethics and commercial morality above business interests made it difficult for his partners to deal with him, and Naoroji was forced to leave the firm.

He started his own company, which initially did very well, but soon ran into debt due to his friends who were in financial distress. However, he managed to overcome his financial problems as he also worked as a professor of Gujarati at the University College, London.

Naoroji used his presence in England to help the people of India by voicing their grievances under British rule. It was due to his efforts that Indians were given the opportunity to compete in the civil service examinations. In late 1866, he founded the East India Association, London, to promote understanding and friendship between the peoples of India and England.

Both Indian and English people became members of this association, through which Naoroji tried to educate the British public regarding the problems being faced by Indians. He was the first Indian to raise before the British public how wealth was being drained from India to England and the fact that British rule was the cause of India’s poverty.

He returned to India in 1869 – the year Gandhi was born. He toured the country and delivered lectures about the objects and work of the East India Association. He was honoured by the citizens of Bombay for his services rendered in London. In July 1875, Naoroji was elected as a member of Bombay’s municipal corporation, and in January 1885, he became the vice-president of the Bombay Presidency Association.

This organisation was one of the precursors of the Indian National Congress, which was founded on December 28, 1885. Dadabhai was thus not only one of the founder members of the Congress, but also one whose vision gave birth to the idea of India’s foremost political organisation.

He had an earnest desire to become a member of the British parliament because he wanted to sit there as a true representative of the people of India, ventilating their grievances and securing justice for them. He failed in his first attempt, but ultimately succeeded in joining the House of Commons in 1892, becoming the first Indian to be elected to parliament.

It was an occasion for great rejoicing in India. Naoroji was also the first Indian to sit on a royal commission appointed to look into financial hardships faced by people in British India.

After presiding over the Lahore session of the Congress in 1893, Naoroji was specially invited to preside over its Calcutta session in 1906, when the Congress faced a vertical split between the moderates and extremists. It was in this session that a demand for swaraj – or self-governance – was raised for the first time.

This session was also historic in that it opened with universal prayers and the singing of Vande Mataram. The resolutions passed in it included a demand for reversing the partition of Bengal. Raising the slogan of swaraj, Dadabhai appealed to the people to remain united and work hard to attain self-sufficiency.

Now an old man, Naoroji was referred to as ‘The Grand Old Man of India’. He was a staunch believer in constitutional methods and belonged to the school of the moderates. Although he believed in swadeshi, he was not against the use of machines for organising key industries in the country. He inspired Jamsetji Tata to raise Indian capital for his iron and steel industries.

A devout Zoroastrian but Catholic in outlook, he did not believe in restrictions of caste, creed and gender. He was one of the earliest pioneers of women’s education and a proponent of equal rights. Amongst his close friends were A.O. Hume, William Wedderburn, Badruddin Tyabji, K.T. Telang and Gopal Krishna Gokhale.

This great hero of the initial phase of India’s freedom struggle died on June 30, 1917 at the age of 91, after nearly seven decades of selfless service to the country. Along with Tilak and Gokhale, who followed him – though with methods at variance with each other’s – Naoroji, in the opinion of this writer, can certainly be counted as one of the three greatest Indians of the independence movement’s pre-Gandhi era.

A befitting tribute was paid to him by Jawaharlal Nehru in parliament while he unveiled a portrait of Bal Gangadhar Tilak in the central hall in 1956:

“We have, to my right here, the picture of Dadabhai Naoroji, in a sense the father of the Indian National Congress. We may perhaps in our youthful arrogance think that some of these leaders of old were very moderate, and that we are braver because we shout more.”

“But every person who can recapture the picture of old India and of the conditions that prevailed, will realise that a man like Dadabhai was, in those conditions, a revolutionary figure.”

(Praveen Davar is a columnist and the author of ‘Freedom Struggle and Beyond’. Courtesy: The Wire.)