The Hindutva narrative paints Birsa Munda as a saviour of ‘Hindus’ and ‘Hindu culture’ against attack from the Christian missionaries. For the Hindutva movement, Birsa Munda is an icon only because he and his followers attacked missionaries and the church. But this is not only a deliberate misreading of history but also a willful deception on the part of Hindutva politics with a dual objective of denying the tribal communities of their distinct identity and also attacking the right to choose religion.

It is true that Birsa Munda attacked Christian missionaries. But these attacks had nothing to do with safeguarding or protecting Hinduism. On the contrary, the attacks – both verbal and physical – signified the emergence of a distinct identity consciousness among the Mundas of Chhotanagpur plateau and other tribal communities who were facing continuous attacks from outsiders, including the Christian missionaries. Just like the ‘upper caste’ Hindu reformers of the 19th century responded to the evangelical attack upon Hindu religious beliefs and cultural practices through various socio-religious movements and reinterpreted Hindu religious beliefs in light of Western-Christian philosophical-theological precepts and ideas of rationality, Birsa Munda did the same for tribal communities of what is now Jharkhand. Moreover, in a period when the term ‘Hindu’ had a very limited meaning, known only to the elite upper caste reformers and had not found any wider currency, it would be preposterous to claim that the Mundas and other tribal communities who lived far away from the so-called mainstream society were fighting to defend it!

Remarkably, Birsa Munda took elements from Vaishnavism, Christianity and Mundari religion to propound his own ‘religion’, which at the same time was distinct from all the three. In this way, Birsa should be seen as an organic intellectual who initiated a social reform movement among the Adivasi communities.

But, Birsa Munda was more than a social reformer. He was also a revolutionary.

Birsa’s revolution: Ulgulan

The Birsaite rebellion was preceded by a series of tribal uprisings in the Chotanagpur plateau and adjoining areas like the Kol insurrection (1830-33), Santhal rebellion (1855) among others, against encroachment of land, labour and livelihood of tribal communities by British imperialists as well as native Indian rulers.

The primary reason for these uprisings was the imposition of the Permanent Settlement Act (1793) which had alienated the tribal communities from the land which they cultivated. This introduction of zamindari had also brought the hitherto unknown practices like forced labour and several arbitrary taxes and rents levied upon the tribal peasantry.

Coupled with this, the influx of Mahajans and Thekedars in the tribal regions, mostly belonging to the so-called upper castes, had introduced the practice of usury in the former moralistic economy of tribal communities, causing immense economic exploitation and hardships for them. The tribal communities had a distinctive label for these outside exploiters or diku. In fact, dikus became the central oppositional figure in all tribal rebellion movements.

The immediate precursor of the Birsaite rebellion was the Sardari movement, whose basic philosophy was “the Adivasis were the first people to clear the lands of Chotanagpur and as such they had an inalienable rights to free access to Chotanagpur land”. The sardars or leaders of the tribal communities primarily adopted a peaceful method of petitioning their grievances to several British government officials demanding the restoration of their rights over the land bypassing the dikus.

From 1858 to 1895, the sardars repeatedly submitted petitions to the highest officials, including the Viceroy of India and even the secretary of state for India in London. In this ‘protest within the bounds of law’, the sardars were helped by Christian missionaries, who they identified with the British race. In fact, a huge segment of the tribal population adopted Christianity not forcefully or anticipating financial rewards, (as the Hindutva forces propagate) but as a political tactic, and also because the missionaries brought with themselves schools and new agricultural technology.

The petitioning mode was only met with disappointment as it brought absolutely no change in the socio-economic condition of the tribal communities. This disappointment with the British government also changed the relationship between sardars and missionaries, as the sardars began to file court suits against the missionaries and Christian Adivasis who had appeared in court on behalf of the British. It was in the backdrop of this failure and resentment against all agents of oppression (the British government, missionaries, their native acolytes and dikus) that Birsa Munda emerged as a social reformer and revolutionary leader who radicalised the sardari movement.

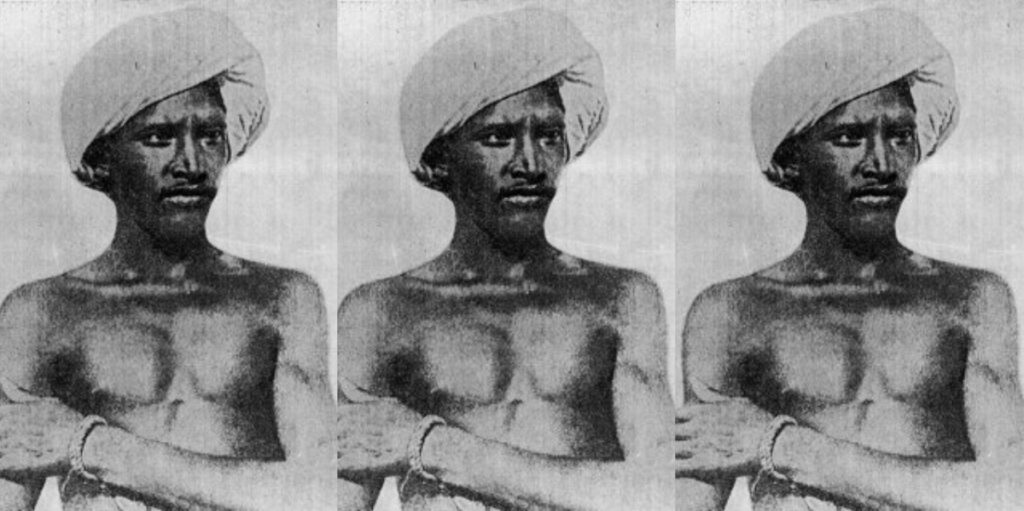

Born on November 15, 1874 to a family of sharecroppers in a village named Chalkad, Birsa received his initial education in a missionary school and also came in contact with a Vaishnava preacher, who had a significant influence on him. It must be pointed out that the region of Chhotanagpur which lay between Bengal and Orissa had come under the influence of the Vaishnava movement launched by Chaitanya in the 16th century. The seemingly and relatively anti-caste and egalitarian elements of the movement had been able to make inroads among the religious beliefs and practices of the tribal communities. This folk Vaishnavism became a part of the socio-cultural life of tribal communities but the cosmology-theology of Adivasi communities remained the same as before. When Birsa adopted few strains from Vaishnavism, he did not do it because it was “superior” but only because they already were a part of pre-colonial, pre-missionary Adivasi life.

In 1893-94, Birsa participated in a local movement to protest against the takeover of village wasteland by the forest department. In 1895, when the sardar movement was on the decline, Birsa claimed to have seen a vision of god, and he proclaimed himself a prophet. Sociologist Max Weber famously theorised that ‘prophets’ emerge during a social crisis. The tribal society of the 19th century, if anything, was undergoing a massive socio-economic-cultural crisis with the imposition of a new agrarian and political system, missionaries’ critique of indigenous tribal culture and the huge influx of dikus disturbing the economic and cultural world of the tribal communities.

In such a society, the prophetic claims and radical message of Birsa attracted a huge number of followers. He criticised many archaic customs, beliefs and practices and called upon his people to remove superstition, give up intoxication and animal sacrifice, prohibited begging and asked people to worship one god. The aim was to diminish the differences that existed between different Adivasi communities and bring them together; first under a single religious movement and later into a single political community.

Friedrich Engels in his study of the German Peasant War (1594-95) has shown that religion, though largely a conservative force, can also play a revolutionary role, particularly when it articulates the discontentment of any oppressed class. When Birsa Munda proclaimed himself a prophet of a new religion with the mission of liberating his community from the yoke of British imperialism and their lackeys, he gave a voice to the economic and cultural dislocations faced by the tribal communities.

After Birsa proclaimed his new religion, people from all tribal communities gathered around him, mostly impressed by his alleged magical and healing powers. Birsa declared himself as the prophet-king who had come back to establish his long lost kingdom. He famously declared: “Let the kingdom of the queen end and our kingdom be established” and asked the peasants and sharecroppers not to pay rents and other taxes. But soon he was arrested by the colonial police and sentenced to two years of rigorous imprisonment.

After being released in January 1898, Birsa began to reorganise his movement and was soon able to gather a significant number of followers behind him once more. This time, the missionaries emerged as the biggest enemy of Birsa as he proved to be a major roadblock in their activities. As missionaries increased their attacks upon Birsaites, the Birsaites decided to strike back.

The ulgulan (rebellion/tumult) began on December 24, 1899. Almost 7,000 Birsaites, both men and women armed with traditional weapons, first attacked Christianised Mundas, missionaries, the Church, shopkeepers and the local police station. The movement spread from Khunti to several districts of what is now Jharkhand. In Ranchi, the rebels even attacked the deputy commissioner of police. The attack against Christianised Mundas was not random or general but specific; only those native Christians were attacked who were believed to be “supporters or agents” of Europeans, missionaries and the British Government.

As the British colonial government mobilised forces, the Birsaites retreated to the nearby Sail Rakab hill, Dombari from where they engaged in a guerrilla war with the colonial police. On January 9, 1900, a bitter battle ensued between the two, which led to the death of twenty Birsaites while Birsa Munda escaped deep into the forest. The colonial government put a reward of Rs 500 on him and he was finally arrested on March 3. Birsa passed away on June 9 in prison due to his deteriorating health.

After his death and in the wake of his rebellion, the colonial government passed the Chhotanagpur Tenancy Act, a lasting legacy of the Munda revolt. Hence, Birsa Munda should be remembered not only as a social reformer but also a revolutionary who challenged the triumvirate of the colonial state, missionaries and landlords, which makes him a source of inspiration for the present-day struggles of tribal communities against the new triumvirate of the neoliberal state, Hindutva and multinational corporations.

(Prabal Saran Agarwal and Harshvardhan are research scholars at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Courtesy: The Wire.)