Owen Schalk

In contexts of class struggle, national liberation, and the fight for self-determination, art is a cultural weapon. It is a tool for educating, for inspiring change. It gives voice to the injustices of the past and present and gestures toward a more just future.

In post-independence Indonesia, the Lekra cultural movement aimed to give “hope and direction” to their nation’s people by creating art that “showed a way out” of present circumstances toward a more equitable future. This was often done through socialist realism, but the movement didn’t limit itself to this style.

Lekra had tens of thousands of members. After the U.S.-backed coup of 1965, however, the movement was banned. Their “way out” was obliterated in the genocidal violence that followed.

During the fight against apartheid in South Africa, the Medu Art Ensemble created posters, songs, dances, and poems to motivate South Africans to resist the white supremacist government. Thami Mnyele, one of Medu’s founders, stated:

the role of an artist is to teach others; the role of an artist is to ceaselessly search for the ways and means of achieving freedom. Art cannot overthrow a government, but it can inspire change.

For his efforts to inspire change, Mnyele and three other Medu members were killed in a 1985 raid by South African troops. The organization subsequently disbanded.

Vijay Prashad writes:

Art itself does not change the world, but without bringing imagination to life through art, we would resign ourselves to the present. Radical artists allude to reality, trying to raise the consciousness of people who might otherwise not have considered this or that aspect of their relationship with others. It is the role of art to focus the people’s attention and build their confidence to struggle against the misery inflicted upon the global majority.

The Israeli government seems to recognize this fact. In over two months of slaughter, Israeli forces have devastated Gaza’s cultural sector, destroying libraries, publishing houses, theatres, cultural centres, and historical sites and killing artists, poets, writers, musicians, calligraphers, and dancers. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) is doing this with the full support of Canada, the U.S., and other Western powers.

Israel’s targeted bombing of Gaza’s creative professionals and cultural sites is part of what Literary Hub describes as an “ongoing cultural genocide.” Gaza’s Minister of Culture, Atef Abu Saif, has called it a “war on culture.” According to Saif:

…the real war is a war on the narrative to steal the land and its rich treasures of knowledge, history, and civilization, along with the stories it holds [but Palestinians] will undoubtedly continue to contribute to human civilization, restoring joy and hope, elevating through singing, music, poetry, novels, stories, and tales rooted in the ever-evolving consciousness, culture, and thought of the land of the first stories.

On October 20, the Israeli military killed Heba Abu Nada, a poet, novelist, and educator whose novel Oxygen is Not for the Dead won the Sharjah Award for Arab Creativity in 2017. Nada’s last words, released by Anthony Anaxagorou on October 24, read:

We find ourselves in an indescribable state of bliss amidst the chaos. Amidst the ruins, a new city emerges—a testament to our resilience. Cries of pain echo through the air, mingling with the blood-stained garments of doctors. Teachers, despite their grievances, embrace their little pupils, while families display unwavering strength in the face of adversity.

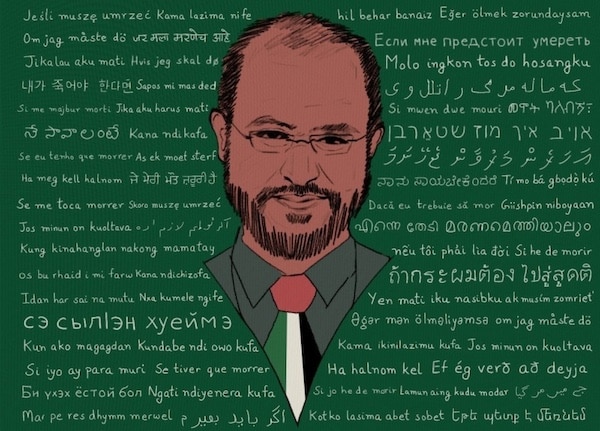

On December 6, an Israeli airstrike assassinated another writer, the Gazan poet and academic Refaat Alareer, with several members of his family. The Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor reports that Alareer was deliberately targeted by the IDF. Prior to his death, Alareer and his family had been sheltering at a school administered by the UN when he received a death threat over the phone. Not wanting to endanger the other refugees, he withdrew to his sister’s apartment, where the Israeli military murdered him with a targeted airstrike.

In his final interview, Alareer stated:

I am an academic. Probably the toughest thing I have at home is an Expo marker. But if the Israelis invade, if they barge at us, charge at us open door-to-door to massacre us, I am going to use that marker to throw it at the Israeli soldiers, even if that is the last thing that I would be able to do. And this is the feeling of everybody. We are helpless. We have nothing to lose.

In addition to his writing and activism, Alareer taught creative writing and literature (including Hebrew literature) at the Islamic University of Gaza. Through his work with We Are Not Numbers (a project established in 2015 by the Euro-Med Monitor to provide English-language writing workshops for young Palestinians in Gaza) and the publication of literary anthologies, Alareer aimed to educate the world about the horrendous conditions Palestinians have been forced to endure under Israeli occupation.

Gaza Writes Back, published in 2013, compiles short stories from 15 Palestinian writers in Gaza. As the jacket reads:

These stories are acts of resistance and defiance, proclaiming the endurance of Palestinians and the continuing resilience and creativity of their culture in the face of ongoing obstacles and attempts to silence them.

Alareer believed that by preserving old stories and penning new ones, Palestinians are not just producing works that can be admired by local and global literary communities. They are asserting their right to the land.

During his 2015 Ted Talk, Alareer told a story about a “native Canadian” during the early years of colonization. In Alareer’s story, a group of European colonizers were discussing how to divide the land when an Indigenous elder approached them. “If this is your land,” the elder says,

tell me your stories.

“Of course, the answer is silence,” Alareer explains.

They had no stories and they don’t own the land.

For Alareer, his efforts to open space in global literature for Palestinian writers were a contribution to the struggle against Israeli colonization and apartheid. As an academic—someone with nothing tougher than a marker at home—he recognized his literary skills could challenge his oppressor’s efforts to deny his people a voice. For empowering Palestinian voices, for speaking out fearlessly against injustice in occupied lands, the oppressor killed him.

During a talk at the Community Church of Boston, journalist Max Blumenthal, who knew Alareer personally, said,

I believe Refaat Alareer’s book tour for Gaza Writes Back was a dangerous moment for U.S. empire and Israel [as an] extension of U.S. empire.

Blumenthal stated bluntly:

He was killed for his words, because his words were so threatening.

This places Alareer in the ranks of great artists who were persecuted and killed for trying to inspire change, like the Lekra members who were murdered by Suharto’s thugs and the Medu artists who were assassinated by apartheid commandos.

Toronto-based writer Sarah Hagi described Alareer aptly:

He worked his entire life to not only become an incredible writer and academic, but to teach other Palestinians how to use storytelling as a tool of resistance. He nurtured so many of his students and brought stories from Gaza that may have otherwise been overlooked to the world.

Since Israel’s killing of Alareer earlier this month, his poem “If I Must Die” has resonated with readers around the world, being translated into over 40 languages and read by actor Brian Cox for the Palestinian Festival of Literature. Other writers have made efforts to popularize Palestinian literature, such as Irish author Sally Rooney, who read Ghassan Kanafani’s “Letter From Gaza” as part of Irish Writers for Palestine.

In Canada, literary culture has divided. When three protestors disrupted the Scotiabank Giller Prize gala with signs condemning Scotiabank’s funding of Israel’s Elbit Systems (a military technology company and defense contractor), they were met with boos from the audience. Giller Executive Director Elana Rabinovitch later said the anti-genocide protestors showed “disrespect to Canadian authors, and their literary achievements that were made throughout the year.” The protestors are facing criminal charges.

In the aftermath of the disruption, Canada’s literary mainstream polarized. Some prominent authors—Waubgeshig Rice, Billy-Ray Belcourt, Anuja Varghese, Omar El Akkad, Noor Naga, and Tsering Yangzom Lama, to name a few—signed an open letter calling on literary institutions like the Giller Prize to endorse a ceasefire and urge the Canadian government to end its material support for the Israeli military. In total, about 2,200 people, including many authors and industry figures, signed the letter.

In response, Canadian authors Sidura Ludwig and Anna Rosner wrote a competing open letter in which they claimed the ceasefire letter had “deep biases” and that its framing of the war on Gaza contributes to “growing hatred of Jews.” The open letter has been signed by over 2,000 “writers, artists, industry professionals and supporters of the arts.”

Canada’s literary community is evidently split on the war on Gaza. Thousands of writers have condemned Israel’s genocidal assault, while others have chosen to tacitly support the IDF’s campaign to erase Palestinian lives, culture, and storytelling.

The hypocrisy of writers, in Canada and elsewhere, who support Israel’s actions is astounding. As Dan Sheehan writes in Literary Hub:

Consider the household names who spent the Trump years cataloging every MAGA obscenity on their Twitter feeds, now silent on the subject of Gaza; authors who (rightly, admirably, and regularly) speak out about Florida book bans and the dismantling of Roe vs. Wade and the incursion of artificial intelligence into the literary space and the January 6 insurrection and the actions of Russia in Ukraine, but who, seemingly, have nothing to say about the U.S.-backed killing of over 8,000 Palestinian civilians [almost 20,000 at the time of writing].

The attack on Gaza is targeting the very ability of Palestinians to express themselves to the outside world. This is why Israel is assassinating poets, novelists, journalists, and other creative professionals.

At his talk in Boston, Max Blumenthal said, “We have to pick up the marker”—a reference to Refaat Alareer’s final interview.

Pick up the marker and throw your marker at the architects of this genocide for the rest of your lives.

It is incumbent on Canadian poets, novelists, journalists—anyone with the means—to write back against this genocide. If Canadians don’t, it calls into question their commitment to the values that supposedly underpin Canadian literature.

Canadian writers: pick up the marker.

(Owen Schalk is a writer from Winnipeg, Manitoba, and a columnist at Canadian Dimension magazine. Courtesy: Canadian Dimension, a forum for debate on important issues facing the Canadian Left today, and a source for analysis of national and regional politics, labour, economics, world affairs and art.)