Indira Jaising

We have all known that the personal is political for a very long time. But when it comes to institutions, there is a sharp distinction between the two. The institution of the judiciary is a constitutional one. Those who occupy the offices of India’s higher judiciary fill the roles in these offices. The office and the office-holder are always distinct. Judicial authority has been vested in these offices to discharge constitutional functions and not protect themselves personally.

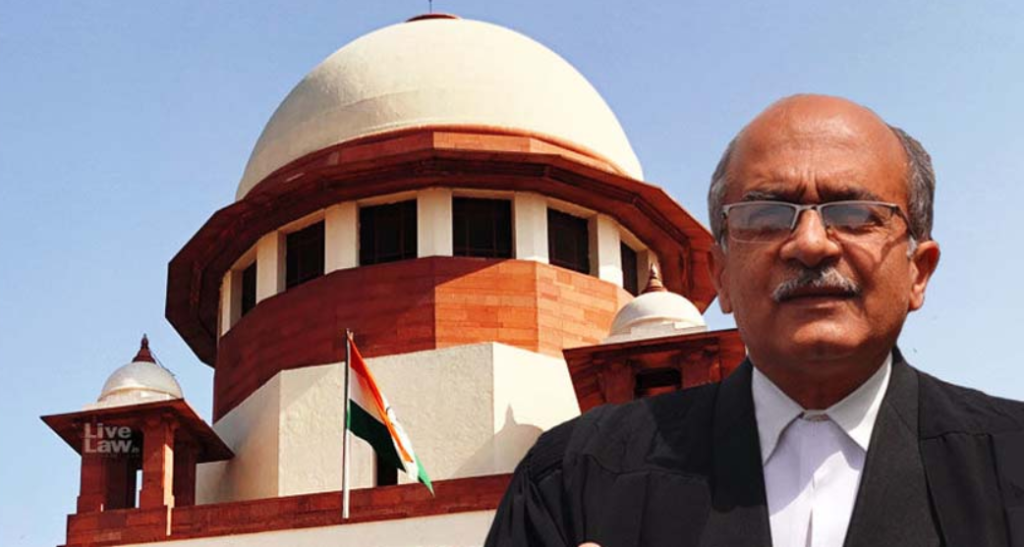

When judges do not make this distinction, the specter of “criminal contempt” returns and this is perhaps best illustrated by what happened on Friday to Prashant Bhushan.

Though Parliament laid down a legislative framework for criminal contempt, the Supreme Court has retained its inherent jurisdiction on the matter and has decided this may be activated ‘suo moto’ i.e. on the court’s own motion. In this case, a contempt petition was presented without the approval of the Attorney General, a requirement under the Act. The court on its administrative side took a decision to allow it to proceed as a suo moto matter bypassing this requirement. The administrative decision to do so, however, has not been made available for either review or scrutiny. We are left in the dark to know how this happened, who authorised it, and why it was so.

Bypassing the Contempt of Courts Act and the need to obtain the sanction of the Attorney General, the court relies on Article 129 of the Constitution as being a court of record with power to convict for contempt. Nobody disputed that power. What was in dispute is the procedure prescribed by law to activate that power, namely compliance with the Contempt of Courts Act. The court would have only grown in stature if it had invited the Attorney General to have his say and create the first level of scrutiny of the application for contempt. There is a purpose behind this safeguard. Not every contempt need be prosecuted, it is a policy decision that the Attorney General takes in the public interest.

Without a vibrant bar, there can be no vibrant judiciary.

By far the most dangerous implications of the judgment is this assumed power—to open the doors to the court at will, and punish for contempt.

Is this even constitutional…being held guilty of a crime without a charge being framed, or the red herring on malintention to scandalise the court? This alone makes the judgment erroneous in law, anti-constitutional, and a great setback for the rights to life and free speech.

It is interesting to note that the court chose a practicing lawyer—one as they point out who has been practicing for 30 years—to hold guilty of contempt of court. Lawyers are the front-line defenders of the independence of the judiciary. They, more than anyone else, know what is going on inside the courts. Judges are their former colleagues and lawyers see judges perform—or not—day in, day out. Judges come and go but lawyers stay. They watch one Chief Justice after another come and go and take or reverse decisions according to their individual views. Lawyers document judicial history in their memories, better than anyone else.

It is, therefore, no accident that the Court chose to target a lawyer, rather than the press.

One of the two tweets in question was a comment on a photo of the Chief Justice of India in casual clothes on a motorcycle, a Harley-Davidson. The judgment acknowledges that this is a “personal” matter. The judges are conscious of the distinction between the personal and the institutional. Where then does the problem arise?

It’s the comment on the courts being locked down denying access to the public that has enraged the court. From then on, the judgment can truly be described as being ‘personally’ directed at Prashant Bhushan, losing its constitutional dimensions. What exactly is his crime – his identity?

He is an officer of the court with 30 years of work, including work in defense of democracy and demanding judicial accountability. He has accessed the court during the lockdown for relief against malicious prosecution and got relief. Therefore, his tweet is malicious and scurrilous. Is that logical?

We are told that the court has handled 626 writ petitions and a total of 12,567 cases during the lockdown. Yet, the important questions about the lockdown in Jammu & Kashmir remain pending before the court including questions about personal liberty. It is clear as day to anyone following the critique about the Court, that Bhushan’s comments were not about the 12,567 cases heard during the lockdown, but about the kind of matters that were not heard. Statistics alone don’t tell you the whole story. It is what you hear, when you hear it, and why you hear it that matters.

In a system when judicial time is in short supply, how you allocate court time determines the quality of justice. It is not measured by its quantity alone but by its quality. The selective nature of the Supreme Court’s determination of what constitutes ‘urgency’ is something that has been under critique for some time now. But the judgment proceeds to attempt to personally defend that conduct of the Supreme Court rather than analyse if such a critique rose to the level of contempt. It is almost as though through this judgment, the Court is attempting to rebut Bhushan, that too without an opportunity of being heard, or tried as charged.

We are told that the comment on denial of access to justice is “false to his knowledge”. But there is a difference between a comment which is “false“ that is factually incorrect and once which is false to his knowledge. Moreover, how can an opinion I hold be “false to my knowledge”? Prashant Bhushan held the opinion that access to justice was being denied. The judges did not think so based on facts and figures. What to hear, what not to hear is a conscious decision, and hence if citizen Prashant Bhushan comments on it, how does it become mala fide? This is where the constitutional becomes personal.

The judges are willing to concede that bona fide differences of opinion on the functioning of the judiciary are permissible in the interest of improving the institution. But on what basis do they find Prashant Bhushan’s comments malicious?

What follows is a refusal to deal with the factual material on record.

“The tweet clearly tends to give an impression, that the Supreme Court, which is the highest constitutional court in the country, has in the last six years (emphasis supplied) played a vital role in destruction of the Indian democracy. There is no manner of doubt, that the tweet tends to shake the public confidence in the institution of judiciary. We do not want to go into the truthfulness or otherwise of the first part of the tweet, inasmuch as we do not want to convert this proceeding into a platform for political debate. We are only concerned with the damage that is sought to be done to the institution of administration of justice. In our considered view, the said tweet undermines the dignity and authority of the institution of the Supreme Court of India and the CJI and directly affronts the majesty of law.”

If, as the court rightly notes, the question of whether ‘democracy is dead’ in India is a political question, then how can a critique of the guardian of democracy not be anything but permissible political speech? The Supreme Court is the guardian of the constitution and democracy. A valid critique of the state of the democratic space in India must within it include the right to critique the actions of the guardians. But this sudden movement to hold the former permissible speech but the latter to be prohibited shows that Prashant Bhushan was held in contempt not merely because the Court found what he said to be contemptuous, but it was because it was Prashant Bhushan who said it. Which makes it seem like a personal battle between the Bench and a member of the Bar playing out as a contempt trial.

Speaking for myself, I am a lawyer since I believe that I am performing a constitutional function in defending by my advocacy our common fundamental freedoms and liberties. My work in court is, in that sense, political.

What the court does here is to descend to the level of self-defence of its own actions.

What are the implications of the judgment for the future? Will it chill the legal profession into silence? If that happens it will be tragic for, as I said, lawyers are frontline defenders of the constitution and, more than anyone else, require the protection as whistleblowers in court. Activists had demanded that the stillborn whistleblower’s law apply to lawyers as well. The time has come for that. We have noticed a recent trend in the executive to target lawyers compelling them to seek justice at the hands of the court. Our courts should recognise this as an attack on the very right to legal representation which will ultimately impact every citizen who needs to go to court, instead of revictimising them.

Without a vibrant bar, there can be no vibrant judiciary. We lawyers are the primary victims of this judgment—be quiet or face contempt, is the message of the court.

The press is unlikely to be tamed by the judgment, indeed it would be wonderful to see blank edits as a mark to protest akin to the days of the Emergency. Or should I say, requiring the press not be critical of the judiciary is like what Justice Denning was once accused of doing, granting an injunction against a frog that it shall not croak.

The judgment is a perfect example of how not to write a judgment. Motorcyclists may want to avoid a Harley-Davidson and ride the humble Hero Honda and discover disease and destitution as Che Guevara did in Latin America.

(The author is former Additional Solicitor General of India and a Senior Advocate at Supreme Court of India. Article courtesy: BloombergQuint.)