In the aftermath of the New York Times’s Project 1619 that appeared in the August 2019 Sunday Magazine section, there have been howls of protest over Nikole Hannah-Jones’s claim that “anti-black racism runs in the very DNA of this country.” Those howls have come from both the right and the left, with Donald J. Trump and Sean Wilentz being prime examples.

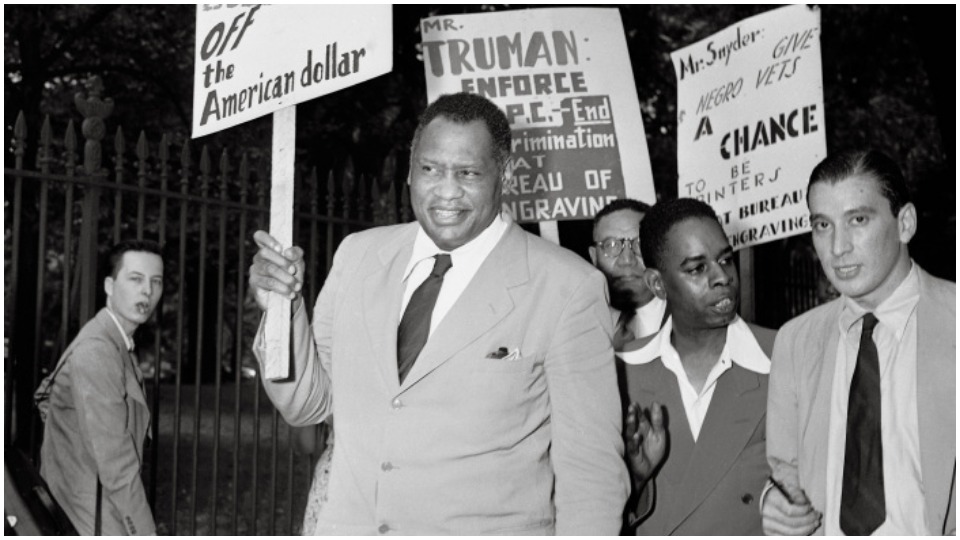

Anybody with an open mind who reads Sharon Rudahl’s superlative A Graphic Biography of Paul Robeson: Ballad of an American will conclude that Hannah-Jones’s statement is truthful. The degree to which racists both in and outside of government tried to “cancel” this African-American icon is shocking. Like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., Paul Robeson was an assassination victim. In his case, the murder weapon wasn’t a bullet but decades of harassment and even a possible drug attempt to make him lose his mind. It was an example of a death by a thousand cuts.

Although it is “merely” a comic book, the term that Harvey Pekar preferred to describe his own and similar works, it draws from a wealth of other books, including Martin Duberman’s highly regarded 1988 biography. However, the relationship between his life’s details and the popular form the book assumes is seamless. It is stunning to see how the minutiae of a man’s life can capture your attention. Of course, with someone like Paul Robeson, the inherent drama can overcome even the most pedestrian rendering. Suffice it to say that Rudahl has written one of the best radical comic books I have ever read.

Paul Robeson was born in 1898, the son of William Robeson, a slave who escaped to the north on the Underground Railroad. During the Civil War, he worked for the Union army and twice risked enslavement when he visited his mother in North Carolina. After the war ended, William Robeson worked as a farmhand to pay his way through Lincoln University and eventually became the Pastor of a Black church in Somerville, New Jersey. His son Paul became an outstanding student in Somerville High, excelling academically, starring in sports, and as a glee club singer. By any objective standards, he was the kind of student any college would admit, especially Rutgers.

Promising students were eligible for a full scholarship there if they came in first in a state-wide exam. However, Somerville High’s Principal kept the exam a secret from Paul, thus verifying Malcolm X’s observation that everything south of Canada was The South. After Paul found out about the test, he spent a couple of weeks cramming. Despite being at a disadvantage, he aced the test and won a scholarship.

Even though he was a powerfully gifted football player who would become the team’s star, white teammates gave him the kind of treatment that Jackie Robinson got. During tryouts, older players ganged up on him and left him battered. Fortunately, the Rutgers coach “Sandy” Sanford saw him the same way Branch Rickey saw Jackie Robinson and intervened to protect him from the racist goons.

Besides leading the football team to victories, Paul was an outstanding student who became Phi Beta Kappa. He was also the Rutgers glee club star but could not accompany it to off-campus social gatherings.

Admitted to Columbia Law School, Paul played professional football on the weekends and sang professionally to make ends meet. Unfortunately, the long train rides took a toll on his ability to keep up with his studies. Before long, he married Eslanda “Essie” Goode, a young lab technician he met during a stay in New York’s Presbyterian Hospital recovering from a football injury. Like Paul, Essie was a gifted student, winning a scholarship to study chemistry at the University of Illinois. After graduating, she became the first Black employee at Presbyterian Hospital.

The couple became immersed in the Harlem Renaissance culture, going to storefront theaters and basement cabarets. Eventually, they ran into theater director Dora Cole Norman who was staging “Simon the Cyrenian,” a play about a Black man who carried the cross for Jesus. Since the lead had come down with Scarlet Fever, she implored him to take over the role since his muscular build made him an ideal substitute. This gig was the debut for an actor whose 35-year career established him as one of the country’s most famous Black figures, enjoying the kind of fame that Muhammad Ali once had.

Like Muhammad Ali, Paul Robeson was outspoken. He was a civil rights activist but also championed working people. His introduction to the left occurred when he was performing in an English production of “Showboat.” He and Essie became part of a regular salon that included left-wing parliamentarians, including H.G. Welles, George Bernard Shaw and Noel Coward. In 1928, he joined a demonstration mounted by Welsh miners who their boss had locked out after trying to organize a union. In her characteristically wry fashion, Rudahl describes the miners as “the blackest white men Paul had ever met.”

Throughout the book, Rudahl comes up with brilliant flourishes that most likely came from her imagination rather than any text about Paul Robeson. I got a big laugh out of an exchange between his son Paul Jr. and his classmate, the son of Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov. As the two were building a snowman, Paul Jr. brags, “My dad is the best singer in the world.” Molotov’s son replies, “My dad can make bombs out of soda bottles.” This witty exchange is what you only get out in a comic book!

Paul Buhle and Lawrence wrote an afterword for Rudahl’s book that is an outstanding summation of the issues posed by Paul Robeson’s life and career. Despite never having been a member of the Communist Party, Robeson suffered just as much as those who were. You can make a case that the American government saw him as an even greater threat, taking away his passport and encouraging the blacklisting that ruined his career.

For some on the left, he remains problematic because of his steadfast loyalty to the Soviet government. However, C.L.R. James, one of the 20th century’s sharpest critics of Stalinism, never held Robeson’s political ties against him. Buhle, who is the author of “C.L.R. James: The Artist As Revolutionary Paperback,” and Lawrence Ware, the Black Co-Director of the Center for Africana Studies at Oklahoma State, offer this cogent appraisal of his political legacy:

Writing in the magazine Black World in 1970, C.L.R. James—Robeson’s intimate friend and ally during the middle 1930s—sought to explain why Paul had remained in a political circle that included communists and retained a certain reverence for the ideals of the Soviet Union, even when all the revelations of bad behavior past and present had been widely exposed. James, for his part, had become for a time a follower of Leon Trotsky and an intellectual leader of the Trotskyist movement in the UK and then the United States. He nevertheless felt the utmost solidarity with Paul’s dilemma as the most fundamental one facing the anticolonial movement. Liberals and left-wing people of various kinds could express deep sympathy for the mostly peasant peoples rising up against their colonial masters. But only the Soviet Union actually provided material aid and training to the young, radical nationalists. In the face of that reality—from Asia to Africa to Latin America and the Caribbean—even the frequently antirevolutionary behavior of the USSR could be overlooked or at least rationalized. Did the Russians encourage uprising in some places and discourage it elsewhere according to their national interests? Surely. But where would the disillusioned revolutionary go? Such were the dilemmas faced by Robeson when confronting the impoverished and undemocratic realities of life in the Eastern Bloc in particular.

I am in total agreement with this assessment. Ever since revolutionary socialism’s birth, contradictions have gnawed away at its heart and soul. People remained loyal to the U.S.S.R. because they saw it as the only counter-weight to a monstrous system. This was particularly true of a Black American like Paul Robeson, who saw it as a system that took care of the working-class. They reasoned to themselves that no system was perfect, especially the U.S.A that tolerated lynching. With the collapse of official Communism, the left no longer has the burden of making excuses for a repressive system. On the other hand, it is faced with a weakened hand as capitalism enjoys carte blanche everywhere it seeks profits. Eventually, that system will collapse because of its deepening contradictions. Or, more accurately, those of us who hate the system will have to strike the blows that force its collapse.

(Louis Proyect, who has been active in the American socialist movement since the late 1960s, is also an active member of the Central American Solidarity Movement. His articles have appeared in socialist magazines worldwide, and he is also a member of the NY Film Critics Online. Article courtesy: CounterPunch.)