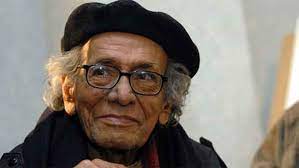

Avtar Singh Sandhu, popularly known by his nom de plume, Pash, was arguably the most influential political Punjabi poet of the 20th century. His works include Loh-Katha (Iron Tale, 1970), Uddian Bazan Magar (Following the Flying Hawks, 1973), Saade Samiyan Vich (In Our Times, 1978), and the posthumously published collection Khilre Hoye Varkey (Scattered Pages, 1989).

Pash was born in the village of Talwandi Salem in Jalandhar, Punjab, on September 9, 1950, when the region was still recovering from the aftermath of partition. It can be said that poetry was in his genes as his father, Sohan Singh Sandhu, who was in the Indian Army, wrote poetry as a hobby. A product of his time and the active Naxalite movement around him, Pash’s poetry always had political overtones akin to the verses of poets such as Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Bertolt Brecht, Yiannis Ritsos and Mahmoud Darwish. This was evident right from his first poetry collection—which he published at the young age of 20—up until those written during his last days.

In fact, he gained the reputation of a rebel following the publication of his first collection, Loh-Katha. When the owner of a brick kiln in the nearby town of Nakodar was killed by self-proclaimed Naxalites, Pash was arrested since he knew them. Tejwant Singh Gill, author of Makers of Indian Literature—Pash (1999) writes, “Any strike announced or agitation launched signalled his arrest.” After the initial arrest in May 1970, he was arrested again during a student unrest in 1972, during a railway employees’ country-wide strike in 1974, and “for an unspecified time during the Emergency.” These arrests had a deep impact on his ideology and writing. Reflecting on the time spent in jail, he wrote in his poem Haath (Hands, 1973),

No one can snatch from me

The play of these hands.

Inside or outside my pockets,

In handcuffs or on the trigger of a rifle,

Hands remain hands

And have their own dharma.

Pash was an avid reader of the German poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht. As a result, he questioned traditions, religious extremism, violence, and social and political structures. He grew up amid the Naxalite movement, and at a time when inequalities and feudalism were being questioned in the region. Ashutosh Sharma, in a 2017 National Herald article, writes that Pash was known for his “scathing criticism of state oppression, religious fundamentalism, feudalism, landlordism, unethical industrialists, corrupt traders and politicians.”

After his release from jail, he came across the works of Russian revolutionaries, Marxist theorists and Soviet politician Leon Trotsky. In Pash: The Poet and Man, Gill writes, “Trotsky renewed Pash’s view of revolutionary poetry. It was now Pablo Neruda with his autochthonous poetry who embodied for him the image of a revolutionary poet.” He was deeply influenced by the writings of Maxim Gorky as well. Inspired by Gorky’s Russian novel Mother, he decided to call himself Pash, after the working-class character Pasha.

Pash was not only a pen name, but also an idea he believed was separate from who he was—an idea that reverberated with the idea of revolution. In his poem Taithon Bina (Without You, 1978), he wrote,

Without you Avtar Singh Sandhu is Pash,

And that is nothing else besides.

By time he turned 22, he had started editing the literary magazines, Siarh (The Plow Line) and Rohle Baan (Raging Arrows)—both Left-leaning publications. In Siarh, he had several times opposed religious fanaticism and separatist ideology, condemning the attempts to divide the nation again on the basis of religion. In his poem, Do te Do Tinn (Two and Two Make Three, 1970), he wrote,

The declaration of accepting demands

is made by dropping bombs.

That loving your own people could mean

spying for the ‘enemy nation.’

And the reward for the greatest treachery

could be the highest seat.

If all this you believe

then two and two make three

and the present can be a mythical past.

In 1986, he moved to America after he received death threats from pro-Khalistan militants. However, that did not stop him from expressing his views against religious fanaticism and the idea of creation of another nation-state. While he was in the US, he brought out a journal called Anti-1947, where he criticised the Sikh extremist violence during the 1980s. He came back to Punjab for a brief period to renew his visa. On March 23, 1988, he was gunned down by militants en route to New Delhi. Even though it has been more than three decades since his death, his ideas, and his fierce and fearless poems continue to be read and recited. Today, his most famous poem, Sab Ton Khatarnak (The Most Dangerous Thing, 1989), has become a poem of resistance and protest that is recited time and again to remind one what the ‘most dangerous thing’ is.

Being looted of one’s labour is not the worst thing.

Nor is police torture.

Even betrayal out of greed

And arrest without warning

Are not the most terrible.

To be frightened into silence is bad

But not really dangerous.

To be drowned in the noise of corruption

Even when one knows one is right is no doubt bad.

Reading in the feeble light of a glow worm

Going through life with a frown are also no doubt bad.

But they are not the worst.

Most harmful to oneself is to reduce life to passivity

To lack intensity of desire

To bear everything

To become a creature of routine.

Most dangerous of all is the death of our dreams.

(The author Manan Kapoor is writer and copy editor with Sahapedia.org, an open encyclopedic resource on the arts, cultures and histories of India. All poems have been translated by Tejwant Singh Gill.)