Ten years ago today, we woke up to the startling news that Honduran president Manuel Zelaya had been removed from his home at gunpoint and still in pajamas, forced into exile across the border in Costa Rica, where I was living at the time. The night before, I had finished a report for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature detailing the political, social, economic and environmental state of Honduras, along with that of the other Central American countries. Zelaya had overseen moderate improvements on the social and economic fronts of small macroeconomic consequence, which had made tangible improvements in the lives of poor working class Hondurans. I thought that maybe if I waited a few days, the coup would be reversed and I could avoid having to rewrite my report.

A decade later, US resolve to greenlight and back the coup d’état in Honduras remains one of the most shameful US foreign policy decisions in recent memory.

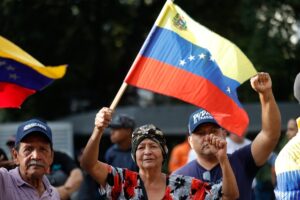

Since the coup, Hondurans have seen the destruction of their country, their democracy, their livelihoods, their human rights. In its first years after, the assassination of lawyers, activists and journalists became a near daily occurrence, shielded by the unscrupulous impunity of corrupt state forces and the constant backing of the US government. In the face of all of this, Hondurans mounted an extraordinary resistance movement that could provide valuable lessons for US progressives. Despite the death threats, police intimidation, censorship, kidnappings, massacres, torture and state terror, Hondurans mounted an intense, furious and savvy opposition.

The military—which has received training from the US—responded with more repression; death squads.

In 2017, the US recognised the results of president Juan Orlando Hernández’s re-election, seen as fraudulent by international organisations and widely considered a sham by Hondurans. The US government has spent a decade sending Hondurans the message that their democracy, their humanity, matters not. With political and economic conditions in continual deterioration—and no sign that things might improve—it’s no wonder that protests have again surged. It is no wonder that Honduran families continue to flee the daily social, structural and political violence that has overtaken their country since Zelaya’s forced removal.

In recent months, the Honduran resistance has stepped up its activities, protesting privatisation policies that threaten to dismantle what little health and education benefits they have. The police have, unsurprisingly, opened fire on the university students demanding president Hernández’s resignation. This week, the police shot and murdered 17-year-old Eblin Noel. News like this comes frequently in Honduras.

As the daughter of political activists from Argentina and Chile forced into exile by the brutal—also US-backed—dictatorships, my own history is marked by the ramifications of the South American coups. But the Honduran example was the first time that I saw a similar process unfold in real time. I also saw, with deep frustration, how indifferent the US was to the Honduran coup, its repression, the daily assassinations and the hurtling social situation. The same indifference—or paralysis—that let tens of thousands of atrocities and disappearances in Argentina, Chile, Guatemala continue over several years.

Two months after the coup, I met Zelaya in Washington, D.C., where he was touring congressional offices and lobbying for political support. It was my first week in D.C. and I sat next to him, amateurishly trying to scribble down every word that was said. In the end, the US government did not back down from its position—it was not “a coup”. Zelaya would not return.

Solidarity activists in the US have been incessant and dedicated in their advocacy work, they have made important strides in getting the US government to back off of Honduras, and probably saved many lives. But the statements, letters, and policy proposals haven’t been enough. Silence around the human rights abuses committed by the US-backed government continues, and the lack of denunciation by people in the US who should care is deafening. We look back and wonder how we could have let the human rights atrocities in Argentina, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Chile occur and continue. We say Nunca Más, Never Again, but it’s happening in our faces right now. It’s been happening every day for ten years.

Yesterday, police dressed in riot gear entered a high school full of Honduran teenagers kneeling on the ground in a powerful, brave and peaceful protest. On the eve of this abominable anniversary, the Honduran resistance is again taking centre stage, hoping that you will notice.

My reason for penning all these words is that I want to express my profound awe and respect for the Hondurans who have survived ten years of violent, dirty, corrupt, murderous repression and yet maintained an unwavering, courageous resistance, in the process risking their lives—and so many have lost them.

I suppose that I just hope that because it’s an anniversary, people will pay more attention. And that Hondurans—whether in their country, on the border, or in US concentration camps—will prevail.

(Sara Kozameh is doing her Ph.D. in History of Latin America and the Caribbean at New York University.)