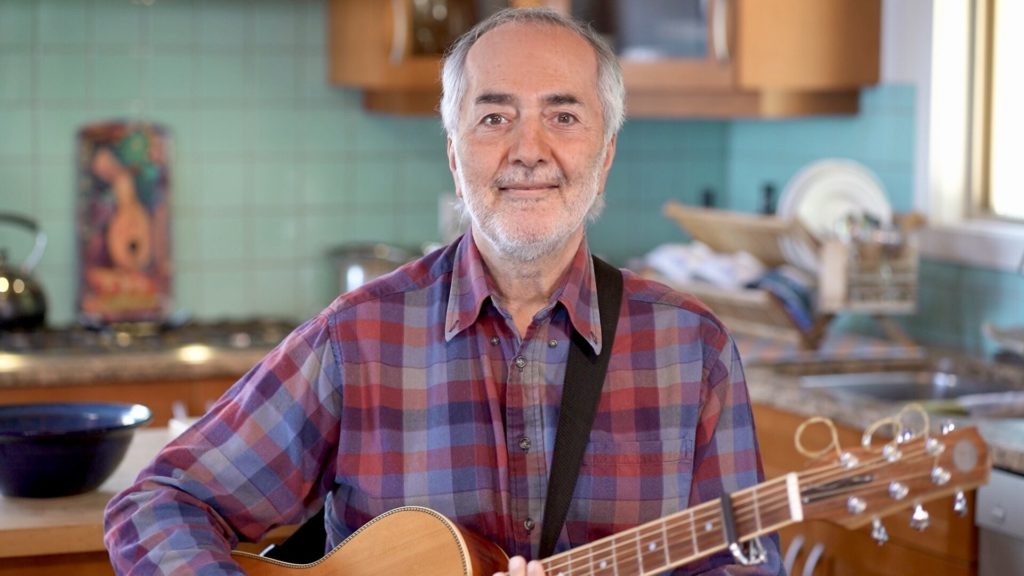

An interview with Raffi Cavoukian

[Today, June 1, is International Children’s Day, a holiday first established by the United Nations in 1925 to honor kids around the world. Children’s singer Raffi has made such respect central to his long career as an entertainer for kids. Once called “the most popular children’s singer in the English-speaking world” by the Washington Post, Raffi has recorded dozens of albums, sold over 15 million records, and written numerous books both for kids and adults.

He also has a long history as a progressive activist. Raffi has been deeply involved in climate change activism, and supported Bernie Sanders’s two presidential campaigns. In honor of International Children’s Day, Jacobin’s Hadas Thier spoke with Raffi about how we can construct a society that puts respect for kids at its core.]

HT: I wanted to first congratulate you for the fortieth anniversary of “Baby Beluga,” one of the most beloved children’s songs ever sung. I heard you talk once about the ripple effect that each human can make on others that we’ve touched. And it occurred to me that your ripple effect is on literally millions or tens of millions of young people across several generations who have, through your songs, gotten to express themselves and celebrate life, and then also have passed on that sense of joy and love to others.

“Baby Beluga” is a very tender song, and many of your songs are a lot more silly, but I think from the most tender to the most silly, one thing that cuts across all your songs, and has made them resonate so deeply with millions of children, is a kindness and respect for children’s minds. I’ve heard you describe a commitment to respecting the child as a whole person — how has that impacted your song-writing?

RC: When I was beginning my work as a children’s entertainer, finding myself with children and parents singing in different settings — at first libraries and then concerts — I thought about who these children were, as people. Because I didn’t have children of my own. And I began to study early childhood. My audience was full of children from three to seven. I wanted to know about the young child, and the more I learned, the more I was fascinated by how intelligent, how spontaneous, and delightful young children are. They’re basically the human explorer at a young age.

So I was full of admiration for who I call humanity’s “primary learners” who, at the time of their life when evolution has seen fit to give them a mode of play as their essential mode of being, they’re learning the most sophisticated human tasks of speech and language acquisition, and grammar and syntax. That told me something profound: that play is an intelligence that we’re not supposed to lose during our lives. Why would we — if it’s powerful enough to fire our profound early human learnings, it ought to stay with us!

I came to admire and respect the young child as a whole person. And that value of respect has guided my whole career and guided the choices that I’ve made both in music that I’ve selected to record and also the way I’ve presented my concerts, and also not doing any commercial endorsements. All of that has been of a piece, arising from respect.

HT: I came upon this beautiful article that you wrote around the time of the Egyptian revolution in 2011. You wrote about the human flourishing that was unleashed in Tahrir Square, and it reminds me of what you were just saying about the power of play and creativity that young children have, and how that’s something we don’t ever want to lose. It’s not just something for children.

You wrote in this article: “We humans were not created for obedience. We are made for creativity, and early on our unbounded spirits dare to sing our own song, our childhood imaginings form original futures in thought, word and deed.”

I think that’s really beautiful. And it struck me that the same kindness and creativity that children deserve, that imbue your music, can also inform a worldview of the kind of society we want for everyone.

RC: Yes. We thrive in creativity. Creativity is a democratic principle, if you think about it. Our original expression to be true to oneself is all tied to our playful explorations of who we think we are, who we feel we are. And it’s the role of caregivers and teachers to hold a loving mirror within which the child can feel affirmed in how it feels to be who they are.

HT: What are your thoughts about the rebellion currently underway in the US and globally against racism and police violence?

RC: I’ve been deeply saddened by the tragic death of George Floyd, tortured and killed by police officers. And if I, a Caucasian, can feel anger and grief over this tragedy, I can imagine the enormous pain felt by African Americans at repeated assaults on their human dignity for decades, centuries in fact.

Massive protest marches in many cities, not just in the US but worldwide, seem to signal a “never again” moment that holds the promise of systemic changes in policing. The militarization of police forces must end. Imagine the goodwill that can grow if law-abiding citizens see the police as “peace officers.”

The “Black Lives Matter” movement is a critically important opportunity to not only seek justice, but to also to teach children about our interconnectedness. The diversity within our global human family is what I’ve celebrated both in song and writings for a long time.

HT: Having a worldview that starts with children, but extends to humanity and democracy, could you talk a little bit about how and why you became an activist, and what’s the relationship between how you approach children and how you approach making change in the world?

RC: It’s this idea of being a citizen who responds to the duty of being a citizen, which is to find ways to contribute to a better society, a better world, a better community of souls, in whose presence a child must grow. So I tend to think along simple lines of inquiry that kind of connect.

Do I want a planet where clean water and clean air, which are entitlements because they are needs, is available to everyone? Well, yes, that’s what I want. I think things through like that very simply. And in our own societies and our own communities, the thought that some might not have access to clean air and clean water, pains my heart because I care about people.

Not caring about people is not an option, because we are human. It is our nature to care. So when we envision a society, it ought to work for everyone. Because the opposite is untenable. Whose child would you leave out? It’s untenable to even consider that. It just doesn’t work.

I’ve had two careers in my life. One is the music career. And then stemming from that, my children’s advocacy. About twenty-three years ago, in 1997, my philosophy, which I call “Child Honoring,” came to me. It actually woke me up from a sound sleep on a Sunday morning. I’d been thinking about what would a society look like that honored its young. I held that question in my mind for a couple of years and was doing some readings to support that line of inquiry. And suddenly I get this vision in which child honoring is just kind of in the air. And I’m just sort of like — “Oh, my!” It was a luminous moment, in which I knew that this was a philosophy that I was being given, one that connected person, culture, and planet with the child at its heart.

Because how often are children considered seriously in strategic thinking about how to make this a better world? Not very often. Sometimes marginally. No, I’m talking about the child being at the heart of a compassion revolution, by which we all might thrive.

So, it was quite something in 1997. I couldn’t stop talking about child honoring. My friends were going crazy. And then in 1999, I wrote a covenant for honoring children, three paragraphs: We find these joys to be self evident, that all children are created whole, endowed with innate intelligence, with dignity and wonder, worthy of respect.

My activism, if you want to call it that, has been exploring how we might conceive of a society that is a just and caring society. How might the universal needs of young children inform the priority needs of such a society? Because young children have universal and irreducible needs, and therefore, what we can say, are their entitlements. That’s not a political word when it relates to young children, because what they’re entitled to is their physiological needs, that they be healthy and grow, be creative and productive.

I had stumbled into something very powerful with this notion of honoring children. And I continued to grow in that feeling that if you take seriously the notion of honoring our young, you’ve got to think about all the children, not just some.

HT: Do you have any advice for parents who are trying to figure out how to engage with their children about what’s happening in the world right now, in a way that isn’t overwhelming but actually engages their powerful minds?

RC: To be a conscious parent means being conscious of our own upbringing and what shaped us — what were the challenges, where was the tension in our childhoods between who we felt we were and how we were brought up. Because we don’t want to repeat mistakes that our own parents may have made with us. How do we participate in being the best guides for children as they’re learning about life?

I think it behooves us to consider ourselves as lifelong learners. So at any moment, we’re learning just as children are learning, whatever they’re learning at school or in home. We adults have got to think of ourselves as growing and evolving human beings. That’s why I would invite parents to take my online course in Child Honoring.

The slogan of the Raffi Foundation for Child Honoring is respecting earth and child. Child learning is an integrated vision where what is earth friendly is actually child friendly, in terms of how we seek to live in a respectful relationship with this planet that births us and keeps us.

HT: I know that even though you live in Canada, you follow US policy very closely and were a big Bernie Sanders supporter for the last two election cycles. What drew you to Bernie’s campaign?

RC: What a sweet and wonderful soul, Bernie Sanders, through the decades, caring about people, caring about workers, caring about all the right things. This man has just been amazing. In 2016, I was so moved by what he accomplished, which was unprecedented, to have a tremendously successful run at the presidency without taking any corporate money. That had never been done before! You’ve got to respect that.

So I was so inspired. I even wrote a song called “Wave of Democracy.” I had this vision of thousands of people singing [starts singing]: “We the people! Stand together in a waaaaaave of democracy!”

Oh, it would have been glorious. The idea that America was born out of a revolution against tyranny ought to inform the current politics. There’s a tyranny of the occupants of the White House against the people. That should be evident to any reasonable person looking at that scene and you would think Americans would say, “Not on our watch.”

“Not me, us.” That’s a beautiful idea. Not me, us. Together. Together, we’re stronger. We the people as an idea — I mean, goodness gracious. And even the hashtag that was used in the UK election a little while ago. “For the many.” That makes sense to me. That rings true in my heart. Society should work for the many. It should work for everyone, ideally, but certainly not for the tiny, privileged, wealthy few who would seek to control things.

No child at the age of reason would vote for that. Children have a sense of fairness. So if you spoke to them about how we should set things up, they would not vote for a society that knowingly left out a percentage of the population, that worked against those people’s rights.

It’s just a matter of caring. That’s what Bernie has been doing. He’s been caring. His legacy, his policies and reflections, are born out of a great deep caring for humanity.

HT: I read in the Burlington Free Press that you hoped to meet Bernie to come and sing “This Land Is Your Land” with you at your show in Burlington Vermont. Did that work out?

RC: No, he wasn’t there that day. But I met some of his grandchildren backstage, and I did get to show the video of “Wave of Democracy” after the concert, actually. Something I’d never do anywhere else. But it was Burlington, Vermont. So we had fun.

HT: Can you speak to the prospects for climate and other kinds of organizing now that Bernie’s campaign is over?

RC: The pandemic has brought us to see that when we are faced with an existential threat to our lives, we can be forced to make really big changes in our society. Look at what we’ve done. People have been staying at home for a couple of months. That’s huge. Businesses have shut down. The economy has just ground to a halt out of a choice to keep people healthy.

So in a similar way, if we understand the climate emergency for the existential threat that it is, we might conceivably, as a society and as a community of societies, respond in a similar way.

Whether we will or not is another thing. Because climate doesn’t feel like a virus that’s going to kill us. It’s a tougher thing for people to feel as a threat. Although you can connect the dots between the science and our lives. And hello, it’s not rocket science. The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2018 report is telling us that we have possibly 10 years to make a sharp turn. This is the climate decade, in which we have to make substantial cuts to greenhouse gases — something we’ve never done but have to. It’s a daunting task!

And we’re losing some time now with the pandemic. It’s the last thing we needed — except that it shows us that huge changes can happen.

Margaret Klein Salamon wrote a book called Facing the Climate Emergency. It talks about feeling fully the climate moment we find ourselves in, including the grief of the futures that we might have imagined for ourselves, but now they might be shortchanged, compromised. And the grief of our children’s dreams for their futures, how climate change might cut short some of that dreaming.

I was having conversations with Lester Brown, a longtime environmental activist and climate activist, and he used to say we need something like a World War II response. And I talked to him at length about this and read up. When Canada and the US joined World War II, the governments mandated civilian companies to stop making what they were making and to instead produce war time materials — weaponry, planes, ships — out of a sense of an imminent threat. So in the US, in the span of some to two or three years, there was a tremendous production of military hardware mandated by the government. Imagine that.

So now that there’s the thought that we’re so late to the effort of stabilizing climate or livable futures, that the only way we’re going to be able to substantially reduce the greenhouse gases year after year in this climate decade is for something like the Green New Deal, and even more. In other words, a similar World War II-style mandating by the federal government of civilian companies to devote their ingenuity to producing the hardware that will harness clean, renewable energy — wind, solar, tidal, geothermal — to scale.

I don’t see how it’s going to happen unless governments mandate it, out of a clear understanding that this is an existential threat to all our lives. So I wrote an essay in January talking about a climate World War III. And as I was writing, I said to myself, “This would be a good war, because it’s not pitted against anybody. A war of survival would be multinational in the best sense of that word. It would be cooperative — imagine that.”

HT: In that essay you called it a “wartime mobilization fueled by love.” I was thinking that it’s interesting that you wrote that in January, and then the pandemic hit in earnest soon after, which as you said, in some ways sets us back, but in some ways, does show us what is possible. At this moment when trillions of dollars are being mobilized, thrown at the economy, it does give a sense of the drastic measures that can be taken.

RC: I’ve been involved with the climate issue for thirty years, off and on. We wasted decades. Everyone knows that Exxon knew decades ago how serious this was. To know and not act on that knowledge, to know and to deceive the public, to know and to obstruct the science from getting out. That’s some kind of crime.

So when you take the 2018 IPCC report to heart — now we’re in 2020 and have ten years. Whatever we don’t do now, only becomes more difficult later and more costly.

HT: How we can nurture this generation of children who are growing up at a moment of isolation and with lots of hope but also fear around them, in a moment of existential crisis?

RC: The word that comes to my mind is “kindness.” For many reasons, in our forced stay at home, in the small spaces that we may find ourselves in. We’re going to have to be very kind to one another, and respectful of space and mood and time, and very forgiving. I know people are struggling with all this.

I’ve taken part in a musical process lately that gave rise to a children’s album — not mine, but a singer from Massachusetts. Her name is Lindsay Munroe. And she now has an album for children called “I Am Kind, Songs for Unique Kids.” Lindsay is a mother of three children, each on the autism spectrum. I came to know Lindsay because I was a fan of her songs, and through our conversations I said to her, “Wouldn’t it be interesting if you wrote songs for children informed by your experience, for your own kids?”

This album is so fun — it’s got such moving, positive, affirmation messages in the songs that can be easily internalized because the songs are so melodic and singable and memorable. I believe Lindsey Monroe’s album takes us into a deeper conversation about what it is to be kind and respect the neurodiversity that more and more we’re understanding is the ground of our being. It’s a call to a deeper compassion through a recognition of the uniqueness of each individual.

(Courtesy: Jacobin, an American socialist quarterly magazine based in New York.)