As world leaders were holding hectic negotiations over climate change at COP26 in Glasgow in November, there was a subtle protest by the inhabitants of Kinnaur district, in the Himalayas, against the impact on the ecology and environment of their region and their very existence.

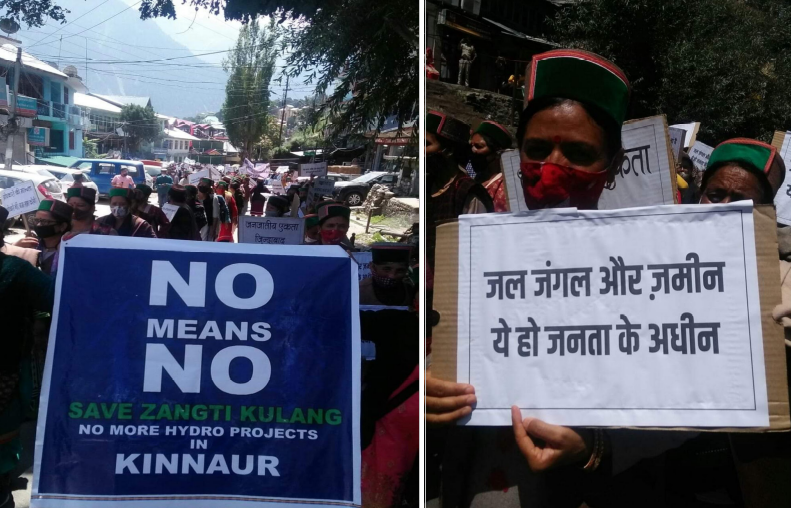

‘No means No’, the clarion call by the tribals, who are locally called Kinnauras in the border district in Himachal Pradesh, is against the proposed 804 megawatt (MW) Jangi Thopan Powari Hydroelectricity Project. Under the banner different tribal groups which also includes Kyang, which means ‘spark’ in the local dialect, the group of young Kinnauras has demanded a complete freeze on the construction of the hydel projects.

In the recently held by-election for the Mandi parliamentary seat, the group gave a call to push for NOTA, or the ‘None of the above option’, which allows voters to disapprove all the candidates. The Kinnauras forced both the major contesting parties, the Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party, to consider their demand. The Congress, which won the election, said at a press conference that Kyang’s demand will be taken up seriously.

The Kyang campaign, which comprises the use of social media, composing songs like Pir Parbat si Pghalni Chahiye and articulating pictorial propaganda material even from the popular Netflix series The Squid Game, links the struggle with international and national movements against climate change. The protesters can be seen carrying portraits of climate activist Greta Thunberg and freedom fighter Bhagat Singh. The ‘No Projects’ slogan links the campaign to sustainable development and protection of the identity of the tribal people.

The last three decades of harnessing hydel power from Kinnaur speaks volumes of the tale of disasters. Under the Nathpa Jhakri Hydro Power Project—now called Satluj Jal Vidyut Nigam Limited—many plants were constructed in the Satluj River basin. Nathpa, a village from where water was diverted through the river dam, became extinct and the villagers had to be rehabilitated in another area.

The impact of these projects is visible in Kinnaur, known for its pristine beauty and producing one of the finest-quality apples in the country, in the form of frequent landslides. The rampant construction of hydel projects and headrace tunnels, which are hundreds of kilometres long, has disturbed the ecology of the region with cracks developing in the mountains and their fertile grasslands becoming dry.

The Jangi project is proposed to be constructed in the most ecologically fragile mountains of the district. The point from where the Satluj enters India from China to Bhakra Dam, in Bilaspur, will be extinct once all the proposed projects come into fruition—Khab-Khab Shaso and Jangi. The commissioned project, Shongtong Karcham, Karcham Wangtoo, Nathpa–Jhakri, Jhakri Rampur, Rampur-to-Behna and finally Koldam and Bhakra have already disturbed the ecology of the region.

Besides these projects in Kinnaur, other plants have been commissioned as well. For example, the 300 MW Baspa Hydropower Project, on Baspa rivulet, was constructed by JSW Group.

With the estimated hydropower energy of Kinnaur more than 8,000 MW, even private players are entering the fray with quality control being increasingly compromised. Some of the projects have started leaking even before commissioning, which can cause a major disaster in near future.

The entire muck extracted from the headrace tunnels is dumped alongside the river bed. A flash flood caused by the melting of upstream glaciers, as it happened in Uttarakhand last year, is enough to carry the entire mud back to the river, causing a destruction of unimaginable proportions.

The Kinnauras, well aware of the dangers of these projects, are building this movement to protect the region’s ecology instead of demanding relief and rehabilitation. In the mid-1950s, after realising the backwardness of the region, tribal leaders had coined the slogan “Peking Nazdik hai Delhi Door Hai (Peking is closer and Delhi is far away)”.

Jeeta Negi, one of the leaders of Kyang, explains why protecting the region is more important than rehabilitation. According to him, 8,000 MW capacity “roughly means Rs 10,000 crore revenue from the waters of Kinnaur”. “The district has a population of nearly 90,000 divided roughly into less than 20,000 families. Even if 5% of the revenue is shared with the tribals, it would mean crores of rupees. However, only large corporate entities have gained maximum profit from these projects,” he says.

The protest is not only limited to the tribal belt of Kinnaur. Recently, some students pursuing higher studies in Chandigarh organised a protest against such projects. “Sooner or later, the movement will call for decommissioning of some of these projects. We want water in our rivers and rivulets. Barren rivers are a blot on mankind and the ecology.” Negi says.

(The writer is the former deputy mayor of Shimla, Himachal Pradesh. Courtesy: Newsclick.)