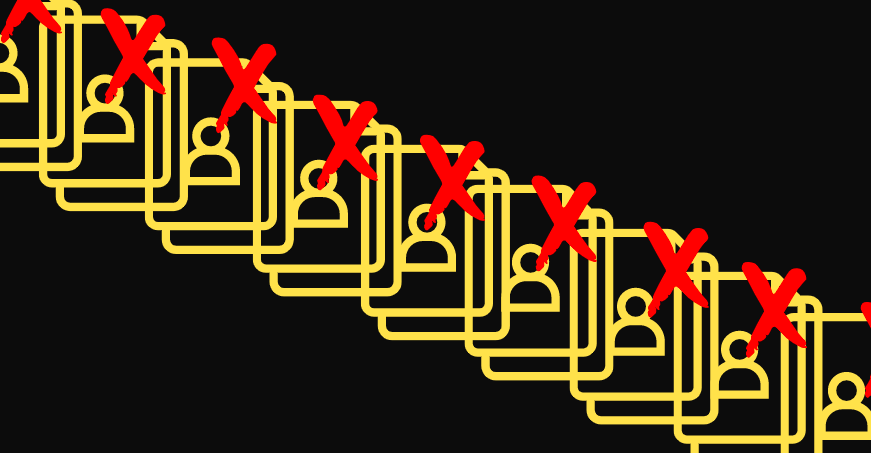

A couple of days ago, the selection panel at GB Pant Social Science Institute of Allahabad, found none of the 16 OBC candidates who had been called for interview suitable for the position of assistant professor.

The position of associate professor for the OBC category was also left vacant for the same reason – ‘none found suitable’.

The news caused such a huge uproar on social media that the institute had to re-advertise the vacant positions within two days.

However, even before the dust could settle, the result of PhD entrance exams of Jawaharlal Nehru University, one of the India’s finest, were announced. In it, a number of candidates from reserved categories, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and OBCs were given abysmally low marks – between one to four out of 30, in the viva voce or oral examinations.

The gross abuse of the tool of ‘interview’ to deliberately deny entry to aspirants from marginalised sections in educational institutions and public sector employment on the pretext that they lack even minimum merit is not a new phenomenon.

In fact, it has been blatantly used for decades in the name of maintaining “quality and standard” by those who aspire to curtail every exercise targeted at the upward socio-economic movement of marginalised sections.

However, lack of adequate data on the marks awarded to reserved category aspirants as well as the conspicuous silence of the mainstream media, which itself is considered highly casteist, has meant that such issues of gross injustice can never garner the attention they deserve.

The implementation of the RTI Act has ensured to an extent that such deliberate attempts of awarding abysmally low marks, which in a majority of cases is due to the caste prejudice of ‘upper’ caste interviewers, will not go unreported. This coupled with access to several social media platforms where such incidents spread like wildfire have immensely contributed in building a public opinion against such acts of injustice.

No institution in the country, including an institution like JNU which is regarded as a bastion of progressive social scientists and historians, can boast itself to be free from such blatant acts of misusing the tool of interviews or viva voce and defying the instrument of reservation.

During my M.Phil and PhD days at JNU, there were frequent reports of the cases where students from reserved categories were given even given a zero mark in their viva voce examinations despite doing relatively well in their written exams. This could have been a subject of every bonafide enquiry.

A couple of years ago, an internal committee of the university under the chairmanship of Professor Abdul Nafey observed a pattern of difference in the written and the viva voce marks across all social categories – which indicated discrimination – and recommended that the discriminatory pattern would get mitigated if viva voce marks are reduced from 30 to 15.

Reserved slots vacant

Joshil K. Abraham and Santhosh S., two scholars, in their Economic and Political Weekly piece in 2010 also noted that only 3.29% of the faculty in the university is Dalit and 1.44% Adivasis.

The situation is same in other premier institutions like IITs and IIMs where faculty positions earmarked for reserved categories are left vacant on one or the other pretext, and the clause ‘none found suitable’ is used most frequently.

According to Siddharth Joshi and Deepak Malghan, in another EPW piece in 2017, six IIMS till 2016 had only two SC faculty members and none from the ST. The other eight IIMs either did not provide data or replied that they do not maintain faculty social group data. The authors collected this information through the RTI Act. Clearly, in the name of maintaining autonomy, these institutions have managed to do without reservation despite continuing demand from the government and other stakeholders.

According to a report published in Hindustan Times, in July 2019, education minister Ramesh Pokhriyal, replied in response to a question in the Lok Sabha that of the 6,043 faculty members in 23 IITs, only 2.5 % were SCs and 0.34% were STs as against the earmarked quota of 15% for SCs and 7.5 % for STs.

At IIT-Mumbai, only six (0.9%) of the 684 faculty positions were from SC community, one (0.1%) from ST and 10 (1.5 %) from OBC category. At IIT-Chennai, of the 596 faculty members, 16 (2.7%) were SCs, three (0.5%) were STs, and 62 (10.4%) were OBCs.

Measures

While the Supreme Court ruled in early 2020 that there is no fundamental right to reservations in appointment and promotions under articles 16(4) and 16(4A) of the constitution, Article 16(1) and 16(2) assured citizens of the equality of opportunity in employment or appointment to any government office.

Also, Article 15(1) generally prohibits any discrimination against any citizen on the grounds of religion, caste, sex or place of birth.

Additionally, Article 29(2) bars discrimination against any citizen with regard to admission to educational institutions maintained by the government or receiving aid out of government funds on the grounds of religion, race, caste, etc. Notwithstanding the provisions in these articles, caste-based discrimination is quite rampant in selection processes in public institutions.

A few small measures are expected to effect big changes in mitigating such discriminatory tendencies in selection procedures in public institutions.

First, the caste of candidates should not be revealed to the members of the interview panels. My own experience of attending some interviews as an expert informs me that ‘upper’ caste interviewers mostly have a tendency of awarding low marks to candidates from reserved categories saying that the latter does not need very high marks for selection. The chances of blatant discrimination in the form of awarding abysmally low marks can be greatly minimised through this way.

Secondly, observers from the reserved categories in interview panels should be from outside the institute and they should have more say in interview panels.

Thirdly, it can be made mandatory that the ‘none found suitable’ criteria cannot be used more than once in selection processes.

(Akhil Alha is assistant professor at Council for Social Development, New Delhi. Courtesy: The Wire.)