Roopa Pai

The highly-acclaimed Kannada poet died on Sunday, May 3, at the age of 84.

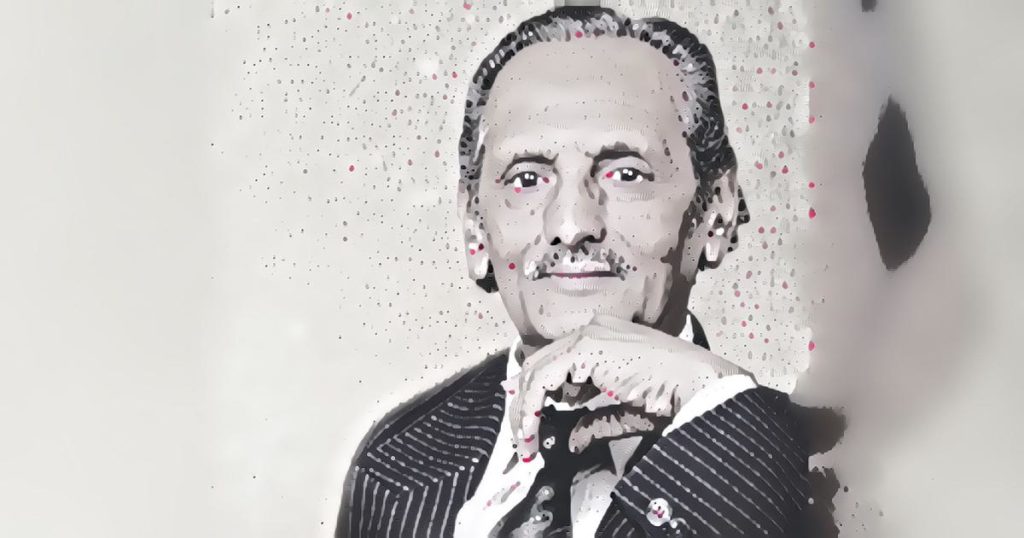

Bang in the middle of the mellow Bangalore summer, right when the gulmohars are turning the pavements and the skies crimson, Kannadiga hearts at home and across the world have been raked by the devastating news of the passing of one of Karnataka’s most beloved and long-standing literary luminaries – the poet laureate K.S. Nisar Ahmed.

For me, the loss feels deeply personal. For the past two years, I have been engaged in translating one hundred of Nisar’s poems into English for a book project. Travel, family commitments, and other projects with more stringent deadlines ate into this one and delayed it unforgivably, much to Nisar’s consternation, until, finally, at the beginning of March, just before the lockdown began, I swore that I would hunker down and finish the remaining poems at a stretch, and proceeded to do just that.

That six-week immersion was exponentially more rewarding than I could have imagined. It left me marvelling at the breadth of concerns that show up regularly in Nisar’s poetry – politics, philosophy, nature, romance, injustice, the angst of the outsider, the minutiae of daily living, the clash of cultures, the crippling frustration of the creative process, love for land and country, and so much more – and the range of emotions each was served up with – tongue-in-cheek humour, black irony, fury, passion, pain, love…

I warmed to the empathy and compassion that illumined his work, grew to anticipate the unfamiliar cadences of the Urdu he often mixed into his Kannada, enjoyed the sudden changes of pace as he played with metre and free verse with equal elan, and was struck by his longevity – this professor of geology had enjoyed a poetic career, in print, for well nigh six decades!

It was extraordinarily difficult to choose just three poems out of a hundred, but it was eventually done. The selection doesn’t do either his prodigious output or his versatility any justice, but there are specific reasons why I chose these three.

The first, “My Words” is the first poem of the first poetry collection he ever published, at the age of 24. When I read it, I was struck by the debutante’s confidence, his immense self-belief, and his conviction that his poetry, slashing like a scimitar through injustice and apathy, would change the world. Ah, youth!

The second, “Amma, Tradition and I”, is a well-known one – funny, autobiographical, and charming in all kinds of ways. I chose it to introduce Nisar the large-hearted liberal – rather than Nisar the poet – to audiences who may not have had the pleasure to know him through his work.

The third, “The News of (Sir CV) Raman’s Death” – is a meditation on the fragility of life and the pointlessness of the various conceits that enslave us through it. The poem’s poignant last verses seemed especially apt for today.

When I called Nisar on April 15 to let him know that the project had finally been completed, he was as delighted as a child. He had nagged and guilted me relentlessly for two years for going slow on the translations, but now he chuckled impishly, saying, “That was very quick, beta, thank you! Poetry translations usually take much, much longer.” Well!

Unarguably, Nisar’s best-known and best-loved poem is “Nityotsava” – “The Neverending Celebration” – a paean to his native state. No translation will ever be able to adequately capture the mood and rhythm of that particular poem, or recreate the thrill that hearing the first bars of the music which it has been set to sends through every Kannadiga soul. What we can all rejoice in, however, is the certainty that Nisar’s poetry will stand for years to come, a radiant Nityotsava to his beautiful life.

Poem 1

My Words

“Nanna Nudi”, from the collection Manasu Gandhi Bazaaru (The Mind Is Gandhi Bazaar), 1960.

My words are as white lightning,

Rip-roaring, thunder-blasting, everlasting,

Through the dark clouds that gather round, confining,

They gleam – oh-so-blinding, sparkling-shining.

By smiling faces that hide hate inside

My words won’t ever be lured;

To cunning and guile and arrogant pride

They will never bow down, rest assured.

My words are not sparks – hot, angry, bright –

That flash but briefly in the dark of the night

They’re a raging inferno that strains for the skies

And transcends the limits of every direction it flies

A conflagration, eternal and outsize.

A roaring river in spate that swallows in its wake

Very mountains that stand in its way;

A torrent unshackled, a deluge untrammelled,

Which on the path of freedom stays.

To the voiceless hordes of suffering humanity

My words give utterance, and validation;

To lives fragile and ungallant and weak

They are safe harbour and firm foundation.

Yes, my words, they’re as white lightning,

Rip-roaring, thunder-blasting, everlasting,

Through the dark clouds that gather round, confining,

They gleam – oh-so-blinding, sparkling-shining.

Poem 2

Amma, Tradition, And I

“Amma, Aachaara, Naanu”, from the collection Sanje Aidara MaLe (The 5 pm Rain), 1970.

Before I was married

Mother checked out dozens of girls

Ground each fine in the mortar of her approval

And handed out her considered verdicts.

That one’s like this, she said, this one’s like that

I’d take a crow over Miss A, and Miss J is fat

This one’s fine, but her tongue is too long

That one’s a giraffe, that rakshasiis just wrong

This one’s teeth are like a toddler’s scrawl

That girl looks like a scarecrow, overall.

And thus, she affixed each with a label –

I remained single for years

Cursed Mother, envied my peers.

Mother was a strict traditionalist

A believer, conservative, ritualist

Quran and burkha and the Ramzan fast

Were things she embraced, espoused to the last.

But nothing riled her so much, truth be told

As our girls strolling burkha-less down the road.

“Look at them baring their bodies, all bold and brassy,

To all manner of men, it’s downright unclassy!

Not an iota of fear or respect

For god or religion, but then what can you expect

From a college girl? Such brazen shrews

Are not for my son; he deserves better, thank you.”

So she brought me

Black-swathed bears who hadn’t a clue

Of modern ideas, or science, or anything new –

The kind that blindly trusted the village quack.

Shuddering, I stepped back

Begged to be allowed to choose my own bride (educated)

But that flight of fantasy was speedily truncated.

“Education-shmeducation! What’s the point of it?

I never went to school – it hasn’t hurt me a bit!

Seeing a girl before marriage? That’s against the rules!

We didn’t and thrived! Come, don’t be a fool.”

Thus did Mother summarily shut me up.

Disgusted, I turned to my trusty backup.

Father was a liberal –

“Let the boy choose his own path

Why should we parents interfere

Just let it go, my dear.” In response,

Amma cried floods of tears

Cast aside food and water, and, as per our fears

Threatened death by water and fire

I shut up. It was all too dire.

Father, man of the world

Familiar with Amma’s anger, her stubbornness

Decided the fuss had reached the limit of reasonableness,

Said, “As you wish, then”, and withdrew

Into silence, cigarettes, late nights; he knew

It was out of his hands now; sullen,

He distanced himself from the villain.

Then one day, out of the blue,

Mother saw the light –

At lunch, she said, “Oh all right,

You pick your educated girl and marry her,

I will not put up a fight.”

Surprised, delighted, and awash in disbelief

I left the table, suddenly nervous, heaving

A huge sigh of relief.

After gazing long and hard, and evaluating

The post-graduate’s photograph, and locating

Her address, we meet face to face; something clicks

And we’re married, seemingly in two ticks.

Silently, I send many grateful words

Amma-wards.

Time now to step out of the house

As a married couple! My beautiful spouse

Dressed in grand saree (tied delicately below the waist)

And sleeveless blouse

Decked out in high-heeled shoes, rings

At her ears and fingers, a string

Of gold around her neck, powder and lipstick

Hair pulled up into a tiered tower, very slick –

And smiling a smile that put all of these in the shade

Is about to step across the threshold, when – “Oh wait!”

She runs back inside. And returns a moment later –

“Now I’m all set!” I stare, struck dumb. The traitor

Is now looking very proper, very pucca –

She’s wearing my Amma’s burkha!

Poem 3

The News of (Sir CV) Raman’s Death

“Raman Satta Suddi”, from the collection Naanemba Parakeeya (The Alien That Is Me), 1972.

I read of Raman’s death

On a morning that had brought a bitter chill

To Shivamogga; the news made me restless, filled

Me with existential dread; unable to bear it any longer,

I decided to go for a walk.

The streets and fields were unchanged,

There was no hushed talk – I grieved

That no one was grieving.

A mile down the road, I ran into Hanuma, of village Navule.

Hanuma, tiller of someone else’s lands,

Behind-the-ear beedi-wearer, frequent thigh-scratcher,

And overall strange creature –

The epitome of the village itself. Waving his hands about,

He was shooing away birds

With a series of practised shouts,

Working the field as he crooned

A decidedly non-classical, outdated tune.

No sooner than he had seen me, he called out a greeting –

“How are you?” “It’s been a while!” “You haven’t been eating?”

He proceeded to tell me how the crop had fared –

“We don’t need the rains anymore,” he declared.

“The daily wrangling with my neighbour, Sir,

Has worn me down, I swear…”

My attention, like the sun in the foggy sky, was a blur,

I nodded, my distraction obvious,

He jabbered on, oblivious.

“O Hanuma, Raman is dead!” I nearly cried out in anguish,

Then stopped myself. How could this simple, unlettered soul

Appreciate what Raman had been, or condole

With me on his passing?

On one side is Raman, on the other Hanuma.

To the latter, who spends his day trawling through muddy slush,

And dines on the kind of stale mush

I would reject even in my dreams;

Who gets drunk each night on country hooch, and deems

Each day to be quite the same as another, who cannot

Tell apart his todays from his tomorrows or yesterdays

Because of their mind-numbing monotony and ceaseless hustle –

To such a one, what difference does it make

If Raman is dead, or Russell?

Hanuma reads no newspaper, does not know I am a poet.

He has no understanding

Of my peculiar hungers or current unease

No way to respond

To catastrophic contemporary events such as these

No appreciation of the difficulties involved in existing

On many different planes; he is barely subsisting –

And yet

He is content.

The field, the landlord,

His saggy-breasted woman, their snotty children,

A simple understanding of god,

The village headman and his squad –

Such is Hanuma’s entire universe.

And yet

He is content.

Unlike me, who is bowed down by weighty matters –

The status of Kannada, border disputes, the sharing of river waters,

Poetry, prestige, pretensions – Hanuma thinks

About uncomplicated things –

A blouse for his wife, school fees for his eldest son,

The debt he owes Haleshi (for his so-called coffee),

Providing, daily, three humble meals for his family –

As you can see,

It isn’t as if he doesn’t have his problems –

And yet

He is content.

I walked on, marvelling, envying, full of a strange disquiet;

When I looked back, both Hanuma, shrouded in mist,

And his now-distant shouts, infinitesimal in the midst

Of Nature’s immensity, seemed meaningless;

His very existence, like mine, utterly purposeless.

One day, Hanuma will die, but I will not be around;

Some day soon, I will be transferred out of this town

The assured local here will become the stranger there,

I will pass on, no one will know or care;

No one will know

My name, my work, my poetry, my life;

No one will know

Of the things that caused me joy and strife;

This familiar sky, this coconut tree, this canal, this hut, this hill –

Their graciousness, their large-hearted goodwill

The meaning they imbued my life with

The emotions they were rife with –

No one will know.

My throat tight, I walked slowly on, alone,

Feeling a weight lift; the news of Raman’s death

Which had caused my world to shift

Seemed suddenly less cataclysmic;

I felt less adrift.