‘Bloodbath’: Activist Nikhil Dey on Budget Cuts to MGNREGA

Gaurav Vivek Bhatnagar

Flagging the continuous year-on-year decline in budgetary allocation for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), under which only Rs 60,000 crore has been allocated in Union Budget 2023-24, the social organisations which had urged a higher allocation to meet the expenditure and pending wages have cautioned that the approach could spell the death of the employment scheme.

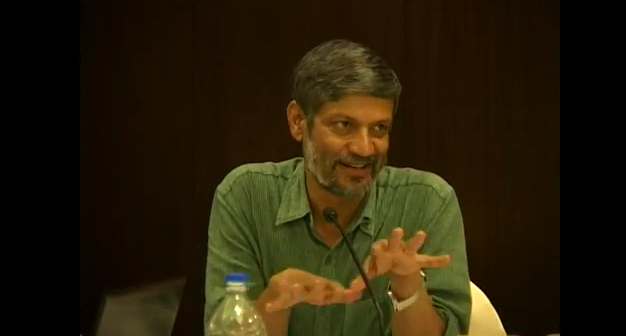

“It’s a bloodbath. They are trying to kill the programme,” said Nikhil Dey of NREGA Sangharsh Morcha while reacting to the Union Budget 2023 slashing the allocation for the scheme by nearly 32% decline from the revised estimate of Rs 89,400 crore for 2022-2023. In comparison to 2020-21, when the allocation stood at Rs 1.11 lakh crore, the amount has almost halved this time.

Rs 2.72 lakh crore was sought to meet expenditure requirements

The Morcha, along with People’s Action for Employment Guarantee, had urged an allocation of Rs 2.72 lakh crore for MGNREGA in 2023-24 in view of the existing inflation, pending worker wages and high demand.

Providing the rationale behind the demand, Dey had said: “The unpaid dues in the financial year 2021-22 were registered to be Rs 24,403 crore against the budget allocation of Rs 73,000 crore. Consequently, 25% of the budget was utilised to clear the dues, thereby creating a shortage of funds for the latter year.”

The two social organisations had also pointed out that with about 21% of the annual budget over the past five years being spent on clearing the arrears carried forward from previous years, and with the unpaid dues being Rs 16,070 crore in 2022-23, it was expected that the dues pending at the end of the current fiscal would be around Rs 25,800.

A look at the data over the previous years reveals that while between FY’16 and FY’21, there was a rise in the allocation under the scheme, it dropped sharply thereafter. The allocation had risen by 55% between FY20 and FY21 – the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic – to reach Rs 1.11 lakh crore. But it came down the following year, FY’22, to Rs 98,000 crore and then dropped further for FY’23 to Rs 73,000 crore. This time, the allocation has been reduced to a new low of Rs 60,000 crore.

‘Allocation is nearly Rs 30,000 less than even the revised estimate’

Talking to The Wire, Dey said only on Tuesday, January 31, had the Morcha issued a press release in which it said that Rs 2.72 lakh crore was needed for MGNREGA. However, the allocation was nearly Rs 30,000 crore less than even the current fiscal’s revised estimate.

On where this would leave the scheme and how it would be impacted, Dey said, “Even the revised estimate of Rs 89,400 crore would leave us nearly Rs 20,000 short of this year’s expenditure. So they are trying to kill the programme.”

The social activist argued that “it is a programme which does not allow less allocation so they are now saying that since the market is giving jobs, when there is a demand we will give more money. The demand is there and they are totally making this up. They have just cut the allocation.”

Nearly 5.6 crore households likely to be impacted

Dey had on Tuesday spelt out how the scheme was of utmost importance for millions of households across the country. He had urged higher allocation, saying about 5.6 crore households benefitted from the scheme in 2022-23.

On calculating the wages for 100 days for each household, he had stated that this would cost over Rs 1.76 lakh crore and along with the material, administration and other costs, the cost could go up to over Rs 2.46 lakh crore. The Rs 2.72 lakh crore figure, he explained, is arrived a by adding the pending dues of Rs 25,800 crore to this figure. Dey had added that anything less would deprive the workers of just wages.

Reacting to the budgetary allocation, Dey also charged on Wednesday that the government has “not given a rupee for West Bengal this year.” In this regard, he had stated on Tuesday that the pending dues for West Bengal, which contributes around 10% of the total workers in the country, have not been cleared since December 2021 and this was depressing the workers.

‘Actual employment is only for 40 days’

Dey also told The Wire that while the scheme aims to provide 100 days of employment to the workers, the actual figure this year has been close to 40 days only. Moreover, he had pointed out earlier that only about 3% of registered workers were able to gain employment for 100 days.

The scheme, as per its mission statement, “aims to enhance livelihood and security in rural areas by providing at least 100 days of employment in a financial year to every household.” However, recent analysis by PRS Legislative Research revealed that between 2016-17 and 2020-21, the average number of days of employment it provided was only 48 days per household.

Also, while the law provides that workers seeking employment and not receiving work opportunities within 15 days are eligible for compensation, Dey said that only 1.7% of the workers were deemed eligible for payable compensation.

(Courtesy: The Wire.)

❈ ❈ ❈

Is MGNREGA the Rotten Apple, Or Does Govt Want it to be?

Alinda Merrie Jan

On December 14, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman informed Parliament that the demand for MGNREGA works is falling. However, official data gives little proof to substantiate the minister’s claim.

Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) is an employment-generating social protection scheme passed by the Indian Parliament in August 2005, subsequently coming into force in February 2006 in 200 of the country’s poorest districts. It was later extended to the entire country in April 2008. Under the Act, any individual living in a rural area and willing to work at the prevailing wage rate is entitled to get work in 15 days, 100 days being the maximum for a household.

The programme works under the principle of self-selection, which means that a person from a household willing to work at the agreed-upon wage rate can enrol themselves under the scheme. As the enrolment and participation are based on the people’s choice, it is safe to assume that the active participants and beneficiaries of the programme are those who are actually in need of them.

Several studies conducted on MGNREGA have emphasised that the workers under the scheme are mostly people from lower caste and class backgrounds. Over the years, development practitioners and policymakers have found that MGNREGA works as a safety net for the rural poor and unemployed. In fact, the impact of the programme extends beyond employment generation.

The minister claimed in Parliament that the demand for MGNREGA works was decreasing. This was actually true for October. But a look at the monthly data for the financial year starting April 2022 paints a different picture. The person-days generated under the scheme peaked in May, falling later. However, November saw a rise in person-days generated, higher than the preceding three months. This shouldn’t be taken as assertive evidence for any policy decision in a country that depends on seasonal employment. The data clearly states that a conclusive statement on the fall in demand for MGNREGA work cannot be made yet.

Why, then, would the government be rushing to conclude that MGNREGA is lesser beneficial than popular belief? It would be hard to guess. However, it is indeed intriguing to look at the performance of the scheme over the years to see who benefits from the scheme and then understand why the government desires to stop it.

MGNREGA – The Safety Net

As mentioned earlier, the beneficiaries of MGNREGA are often the marginalised rural poor. Given that the wages offered under the scheme are much lesser than the minimum wages in several states, the demand for the scheme points towards several interesting reasons. To begin with, MGNREGA serves as a safety net for the rural poor. This is evident from the data on the change in demand for work during or immediately after economic shocks.

Undoubtedly, the two major economic events that shook the nation in the recent past were the demonetisation of late 2016 and the COVID-19 pandemic that hit the world in early 2020. The impact that these two have on the demand for MGNREGA works speaks volumes about the benefit it has for the rural poor.

In November 2016, the BJP-led Union government withdrew overnight the high-value notes of denominations of 500 and 1000. This effectively removed 85% of all currency notes from the economy and destroyed supply chains, affecting agriculture, small-scale traders, and manufacturing and industrial sectors heavily. The move undoubtedly had a huge negative effect on the informal economy, affecting millions of workers across the country as about 90% of the country’s workforce is informal workers.

Evidently, MGNREGA was one option that saved millions from a massive fall. The hasty implementation of the Goods and Service Tax in 2017 further choked the informal economy that employed millions of unskilled and semi-skilled workers. The demand for MGNREGA has seen an increase since 2016. Clearly, employment options in the urban sector were looking bleak. A steep increase in MGNREGA demand was seen in 2020-21. This was the time when the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world. On the eve of March 24, 2020, the Prime Minister announced that the country would go into a lockdown in less than four hours.

Needless to say, the move was unplanned and hastily announced, leading to a lot of confusion and panic. One of the most severely affected groups was migrant workers. The following days saw thousands of migrant workers walking back to their homes, several of them losing their lives. As the government was pressured to arrange transportation for these migrant workers, the concerned minister informed Parliament that about 10 million migrant workers went back to their places of origin during the lockdown. They also said no data was available on the number of people who died en route during the period.

What India witnessed then was the largest reverse migration since Independence. A recent study by a group of migration researchers using visitor location register (VLR) and roaming mobile data estimated the number of migrant workers who went back to be about 44.13 million and 26.3 million during the first and the second lockdowns, respectively. With the uncertainties in the labour market, MGNREGA provided assured hope to keep these people and their families alive. The sudden jump in demand for MGNREGA works in 2020-21 is hence explained. Several studies also found that MGNREGA compensated for the loss of income during the pandemic. Clearly, the programme has worked as a safety net for the millions who lost their livelihood during the pandemic.

The continued high demand for MGNREGA, even as the lockdowns were lifted and migration was back in place, shall not go unnoticed. Though there was a fall in MGNREGA works, it still hasn’t fallen behind the pre-pandemic levels. Take a look at the work demand for November over the years. The demand for November 2022-23 has fallen from its peaked 2020-21 numbers but is still higher than the pre-pandemic level of 2019-20. Experts suggest that this could be because of the dip in farm jobs, the lack of sufficient non-farm jobs in rural areas, and the dearth of hope or confidence in further employment generation. People are not confident about getting work elsewhere; they are largely dependent on the lower-paying MGNREGA works. Precisely, MGNREGA continues to help millions stay out of poverty and unemployment in rural India.

The Rational Economic Decision

While MGNREGA provides a safety net, it wouldn’t be the first choice of most workers. This is because of the disparity in wage rates. Even though MGNREGA had its wages revised earlier this year, it is still much lesser than the minimum wages in most of the states. Some states, like Kerala and Maharashtra, have a gap of about a hundred rupees between the wages provided under MGNREGA and the minimum wages for unskilled workers, which is much lower than the actual wages paid. Being the rational beings that economists call them, workers would choose jobs that would pay them better, provided they have the choice.

Furthermore, MGNREGA guarantees only 100 days of work in a year for a household. It means that the people who get into it would be unemployed for most of the year if this is their primary source of income. Yet, the high demand for MGNREGA works tells an interesting story of the dire state of the country’s poor. When people settle for lower wages, it indicates a higher level of unemployment and the possible risk of being unemployed in the near future. Expectations of work and income are pretty low, and given that inflation continues to be high, the rural poor are trying everything in their capacity to simply stay alive.

The obvious positive trend in the person-days of work generated under the scheme points towards the increasing dependence of millions on work that pays less than minimum wage and for fewer days. For a government that promised two crore jobs/year, people turning up in large numbers for MGNREGA despite irregular payments and hassle ought to be a cause of concern.

It is also to be noted that several states have been requesting the Union government for higher wages and increased person-days of work. This is especially true in the case of states that have seen a huge reverse migration during the pandemic. However, the Union government has been delaying wage payments and providing lesser than demanded work. This has also led to widespread protests by workers as well as states.

Benefits Beyond Income

The dualistic models suggested by economists in the second half of the 20th century explained rural-urban economic migration and developed the debates around the informal economy. Two exogenous shocks that badly affected the country did the most harm to this informal economy that the majority of the people of the country rely on. MGNREGA was the one hope they had at a guaranteed job, a guaranteed source of income, however less it may be, at least for a part of the year. Social security measures such as MGNREGA and the PDS system helped the poor of the country, especially the rural poor, to explore the possibilities of a better livelihood in the growing cities. As much as this sounds contradictory, there is a logical explanation.

Most unskilled migrant workers who move from the villages to cities for informal work are often men who leave their families behind at home. This is made possible not only because of the possible higher earnings in cities but also the backup option their families have at home – the guaranteed 100 days of work for the household and the provision of food grains at subsidised rates. It allows them to move in search of better livelihoods, knowing their families would not starve. MGNREGA is the hope that helped the people who built our modern cities move from their villages.

This is not limited to times of crisis alone. The programme aimed to provide guaranteed employment for the rural poor burdened with disguised unemployment and seasonal unemployment. As much of the agriculture in the country is still traditional, the existence of seasons and the cycles of employment and unemployment also impact the livelihood of marginal farmers and landless labourers. An employment guarantee scheme helped them stay employed throughout the year and not fall prey to debt traps for survival in lean seasons.

The idea of economic productivity, especially when it comes to social security measures, is an altogether different debate. While MGNREGA provisions for the creation of tangible public assets like roads, canals, and public wells, among others, there are far more intangible benefits that MGNREGA has for households in rural India. The earlier studies on MGNREGA have emphasised its impact on childcare and children’s education. It has helped more rural women to be a part of the paid labour force, with a steady income and agency that comes along with it. It has also helped in greater political participation of women and the marginalised. Eliminating contractors and intermediaries has also helped make them less vulnerable to exploitation.

A much pressing concern, therefore, is the timing of the disapproval the government has for the programme. In times of economic shocks, especially in a country with about a fifth of its population in absolute poverty, one would expect a democratic government to take up and implement schemes and projects that would help the citizens live life, at least of subsistence. The requests by state governments to expand the programme in terms of its duration, tasks, and increased wages underscore the benefits the programme served the people during difficulties. The growing unemployment, risks of poverty, and inflation has also led to demands for extending the scope of the programme to urban spaces. Unfortunately, stripping the poor of chances at meagre livelihood seems like the interest of the current government.

An Adamant Government

Why has the government been keen to establish that the demand for MGNREGA works is falling? The timing of the statement amidst the rumours of the government trying to wrap up the programme cannot be considered a coincidence. The Finance Minister’s statement was also corresponding with the demands by the states to clear the dues on the MGNREGA payments to them. Of the Rs 7,655 crore that the Centre owes the states, Rs 3,207.43 crore is pending for material components, and Rs 4,447.92 crore is pending as wages. More than half of the pending wage payments are due to a single state – West Bengal. The second and third in line are Kerala and Tamil Nadu, respectively. Keeping aside the political differences in play here, deferring payments for work done is criminal and outright cruel, especially in times of crisis.

In a silent move, the government has also decided to remove agricultural activities in MGNREGA. The works provided now are limited to tangible asset creation, reducing possible tasks that could be taken up under the scheme. At a time when states have been asking to create more jobs under the scheme, the government has practically restricted the possible number of jobs that can be generated. Adding to it the deferred payments and unforeseen uncertainty, it seems that Sitharman was prophesying what is on hold for MGNREGA. And this did not start recently. The lower budgetary allocation for MGNREGA was criticised by policy experts and workers’ unions alike.

It wouldn’t be misplaced to read that one of the first things the government went for during the lifting of the lockdowns was to reform the labour codes against the interest of the labourers themselves. A few states in the country did reduce the minimum wages and the right to unionise for workers. While the underlying logic was to incentivise the producers to build a stronger supply side, the fact is that almost all of the incentives given by the government through economic packages and otherwise during the lockdown were all for the corporates. This includes tax exemption, lowering tax rates, and writing off bad loans. While much was given to the supply side, demand building and keeping most of the common people alive seemed to have been missed by the policy experts.

The ruling party, which has been in power for more than eight years now, promised to create 100 crore jobs. Not only has this promise remained unfulfilled, but unemployment in the country has also gone up drastically. The labour market has been facing high levels of precarity for decades. Various international agencies have placed us in alarming positions regarding hunger, malnutrition, and poverty indices. The government trying to bulldoze a programme that guarantees income and survival in such desperate times is cruel and a mockery of the people.

Programmes such as the MGNREGA helped the rural poor live dignified lives with assured income. Taking away that would mean taking away not just a work guarantee programme but a lot more. It would mean an end to a working population who could ‘choose’ to work. It could also mean the end of economic agency, freedom, and capability for the rural poor, especially the most vulnerable of the country. Destroying MGNREGA could be the final step in creating a vulnerable population that could become modern forms of bonded labourers or, worse, enslaved people in a neoliberal economy.

(The writer is an independent journalist. Courtesy: Newsclick.)