From Karnataka in the South to Uttar Pradesh in the north, India is witnessing a new brand of casteism patronised by the Hindu Right in power. It is backed by the ideological and organisational might of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), which is trying to smother the rebellious Dalit identity under its hegemonic project of “Hindu unity”. As an inevitable countercurrent, there is also a new anti-caste genre spearheaded by Dalit creative forces. They are proving second to none in developing cultural products with a universal appeal, from literary works to new cinema. They are setting a radical agenda in mass culture, challenging Hindutva hegemony and its underlying upper caste consolidation head-on. This is clearly visible in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

Literary Salvo against Saffron in Karnataka

Those who love democracy and secularism have had too much bad news from Karnataka in recent times—from the hijab ban to curbs on azaan, trumped-up issues with halal meat, the communalised revision of textbooks, an anti-conversion law, and flash mobs taking out yatras to attack the shrines, shops and homes of minorities. But now there is good news.

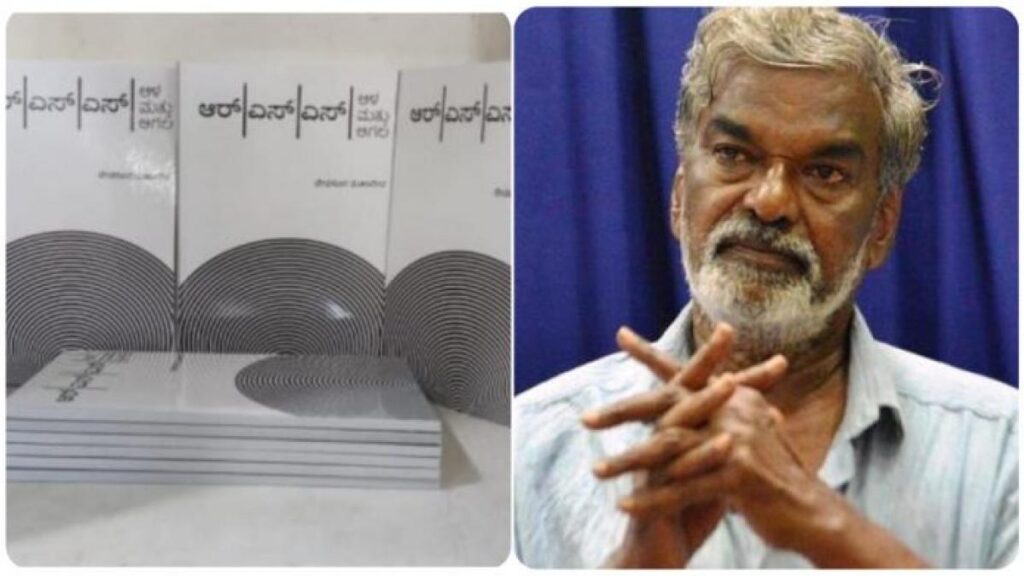

Devanur Mahadeva, Karnataka’s prominent ideologue and Dalit movement leader, has published a book titled ‘RSS: Aala Mattu Agala—RSS: Its Depth and Width’. The publication of this book, critical of the RSS, was a mega event. Innovatively planned as a big-bang event, it had six prominent publishers come together to release it on the same day. Thanks to the still robust literary and cultural networks of the Kannada intelligentsia, word about its release spread quickly, without any stage-managed commercial promos.

‘Depth and Width’

The 64-page booklet (priced at Rs. 40) unveils a unique subaltern critique of the Sangh Parivar’s hegemony. Its critique is not limited to aspiring for conventional liberal democracy and it is premised on a quest for radical social justice. The six publishers had released 9,000 copies, but almost all sold out within a week. Reprints are on the way. The unprecedented response to the book has had taluka-level publishers publish it to cater to the growing demand. It is a rare feat for any serious non-fiction work.

Most importantly, the overwhelming number of readers signals that it is not the Dalit youth or activists alone who are reading it but people from all social backgrounds. The attraction among non-Dalits to a Dalit-centric, Ambedkar-related text is a significant development. Perhaps it means the tender shoots of a new cosmopolitanism, liberal multiculturalism, and democratic composite culture will sprout.

Dr V Laxminarayana, a comrade-in-arms of Mahadeva in the Dalit and radical movements and Karnataka convener of the All-India People’s Front, told NewsClick, “Devanur Mahadeva shows in his book that Golwalkar’s vision was based on three lethal ideas. The first is to uphold ‘Purusha Sukta’ of the Rig Veda, which laid the basis for a hierarchic and oppressive Varna system. The second is the rejection of Ambedkar’s Constitution to maintain chaturvarna, and third is the glorification of Aryan supremacy. He shows how, based on these three principles, Hindutva ideology is anti-Dalit and anti-working people to the core. Mahadeva also strategises for the defeat of the BJP in Karnataka in the next election by calling for a broad unity of anti-BJP forces.”

Other activists NewsClick spoke to in Karnataka feel the politics of Mahadeva’s book is not just resentment and protest. Instead, it is an assertion of dignity, autonomy and independence and speaks to the rise of a leadership of the most oppressed within the democratic arena. It is not a lament expressing the oppression of those excluded and marginalised. Instead, it reflects their confident claim to an independent social and political role and a direct challenge to Hindutva. The book is not confined to encounters with upper caste dominance in villages or mohallas but challenges Hindu elite caste political leadership across India.

Mahadeva pioneered Karnataka’s autonomous Dalit movement in the 1970s, just after a similar movement made its mark in neighbouring Maharashtra. Like the Dalit Panthers of Maharashtra, the new Dalit assertion in Karnataka was led by the Dalit Sangharsh Samiti or DSS, and Mahadeva is one of its founders. For more than four decades, he has been a key strategist of the Dalit movement and advocated a “third force” in Karnataka politics based on progressive movements. It would be a movement of the Dalits and include the movements of farmers, women, labour, the radical left and civil society groups.

Mahadeva has flourished as an author and literary figure and is a Padma Shree awardee for his contributions to Kannada literature. He and comrades such as late D.R. Nagraj have ensured that Dalit literature is more than a match to other literary genres in the vibrant Kannada literary arena. Politically, he remained an independent leftist and ardent associate of Dr Rammanohar Lohia.

While the Hindu upper caste communal moorings in Karnataka was acquiring a mass populist dimension, and the anti-Muslim bias of the Hindu middle classes was spreading like a virus, Mahadeva’s book on the RSS has landed like a bombshell. The thousands of copies it has sold within a week establish that there is a large audience for anti-saffron literature in Karnataka. It also confirms the Hindutva surge in Karnataka would not go unchallenged.

New Dalit-Centric Cinema in Tamil Nadu

While the literary arena still dominates popular mass culture in Karnataka, in neighbouring Tamil Nadu, the Tamil film industry, Kollywood, has taken its place. It is a highly politicised arena in which the histories of Dravidian politics and the film world are inseparable. A new genre of subaltern Tamil films, which many call “Dalit cinema”, is making waves. Pa. Ranjith, its forerunner, was just 29 and barely out of arts school in 2012 when he made his debut.

S. Kumaraswamy, a prominent left leader in Tamil Nadu, summarises this phenomenon for NewsClick: “Pa. Ranjith epitomises new Dalit cinema, which is not about dirt and grime or drowning in tears but about life and full of colour. It is about struggle and assertion and questioning the values of caste-ridden Hindu society. It is also about reaching out to the toiling masses of other castes.”

Still, Pa. Ranjith’s films have been huge commercial successes. His Sarpatta Parambarai was viewed in 150 countries through OTT platforms. In the film, the hero takes a heavy beating, sinks low, and rises again to touch the skies. His inspirational message to the Bahujan is ‘Neeye oli—Be your own light’, and it was acclaimed by all who saw it. The New York Times called it a “must-watch movie” on OTT. In Pa. Ranjith’s Pariyerum Perumal, a Dalit student seeks to study and succeed as a lawyer to fight for the oppressed. His Kabali and Kaala, both made with Rajinikanth, were megahits. Kaala speaks out against Hindutva, while Kabali strikes out against the oppression of Tamils in Malaysia. His Attakathi and Madras were about the throbbing urban life of Dalits and their determined assertion against politically-patronised urban mafia.

Pa. Ranjith blazed a trail in Dalit cinema, but other film-makers such as Mari Selvaraj and Vetrimaran have sustained the trend with their movies. Their stories revolve around the lives of “hidden” and “denied people”. In Vetrimaran’s Asuran, a Dalit hero leads a struggle against oppressive upper-caste kulaks and mobilises peasants from toiling castes.

“Memory cards might have replaced costly film rolls in this hi-tech age, but memories—of oppression and struggles—are retrieved and retold as powerful aesthetic stories so that society will not sink into the morass of forgetfulness. In their political message, these films are a rallying call against Hindutva, as they shake the roots of the status quo,” says Kumaraswamy.

True, there is an element of glamorisation and romanticisation of Dalit existence and resistance, which perhaps is unavoidable in film-making. But the cultural constructs of caste and anti-caste are embedded in real-life oppression and inequalities. Films with stark Dalit motifs and urban themes from Dalit lives, too, become box-office hits now. Raising the cause of Dalits is no longer a narrow voice but becoming a much larger moralist proposition with a democratic imprint. It has as much appeal among non-Dalits as among the Dalits. This is a qualitatively new element in Tamil social cinema.

Mahadeva and Pa. Ranjith have individually stormed the elite/upper caste bastions of the Kannada literary genre and the Tamil film industry, respectively. Their work does not revolve within a limited horizon but pitches into a broader horizon of socio-cultural and political democracy. Both have established their artistic supremacy in their fields. Maybe their success is nascent, but they have proven that a new generation has arrived to take the lead of the oppressed in the exclusionary cultural and literary arenas. In this sense, it is good news for all democratic and secular aspirants.

Incidentally, this new ferment in the Dalit discourse spotlights the historical challenge of democratisation (on the social plane and at the grass-roots) in plural but hierarchic and polarised societies. It marks the outbreak of popular liberalism at the social level, even if fleetingly. This is the kind of outbreak that made Barak Obama president of a racist white supremacist society.

What is happening in India is not conventional Dalitism pitted against episodic upper caste cruelty. This is a wider social-democratic and political assertion. It shows how saffron governments are doing injustice to Ambedkar by trampling his democratic values and the constitutional guidelines on liberty, freedom of expression, and the rule of law.

Will the social-democratic assertion taking place in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu hold the mirror before relatively more conservative Gujarat or Madhya Pradesh or Uttar Pradesh and Bihar? Will it inspire the progressive intelligentsia in the saffronised ‘cow-belt’ regions? Will new Devanur Mahadevas and Pa. Ranjith’s rise in the not-so-vibrant cultural fields of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar? History tells us only time stands between good news from the South echoing in the West and North.

(The author is a commentator. Courtesy: Newsclick.)