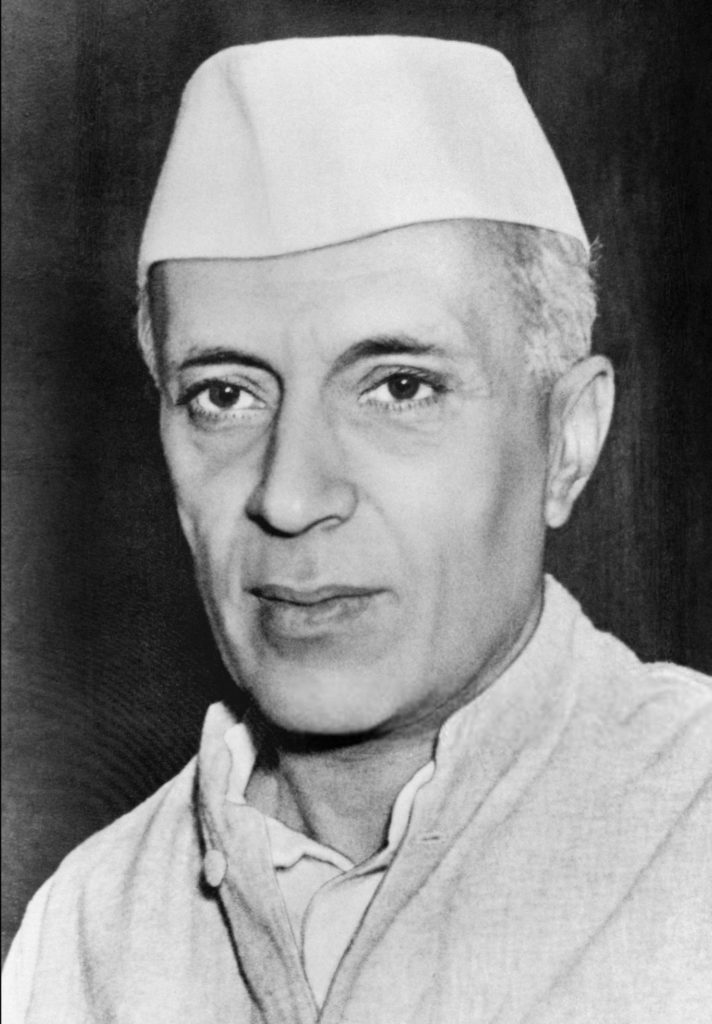

Arjun Sengupta

Jawaharlal Nehru was not the only aristocrat who entered politics and joined the struggle for independence in India. There were also others who came from similar background of secure family roots, extravagance and style, and who courted imprisonment, flirted with hardship and enjoyed the luxury of sacrifice.

If Nehru was a romantic, a politician who was more a poet than a schemer, a revolutionary who loved to philosophise more than to operate, he was not the only one of that kind in India. A whole lot of Indian politicians, especially of the Left-wing variety, were romantic revolutionaries, who had an idealised view of things and their relations in India and who spent their lives in building, destroying and rebuilding their theoretical model of the enemy whom they would fight. If Nehru was an intellectual dilettante existing at several planes and levels, so were most of the Leftist intellectuals in India.

Impress on History

THE point is not that Jawaharlal Nehru was all these but that in spite of being all these, he was the only socialist who left a deep mark on Indian history, who made the greatest contribution to the process of socialist development of our country. Not that he ushered in socialism in India, not even that he set the country on the path of socialism from which there can be no turning back.

But he set his country in the mainstream of socialist development, made socialism in India a vital force that counts, a factor that any move towards reaction has to reckon with. Socialism together with democracy has seeped through the authoritarian structure and the ideology of irrationalism of the Indian society and has reached the broad masses of our people; and no one has played as great and as effective a role in that historic process as Nehru. To deny that is to deny the reality of Indian history.

Pathological Jealousy

TIME and again elements of the Indian Leftists have ignored this positive aspect of Nehru’s role in history. Instead they have magnified the implications of his class roots and social surroundings with almost a pathological jealousy.

That Nehru’s mode of living was out of tune, that his dog was more well fed than an average Indian, that his daughter “alternated between Sabarmati and Swiss schools”, that the childhood memories of the Nehru children are an “amalgam of prisons and chocolate bars” are judgements that are not only irrelevant but also betray a total lack of perspective.

What is important is not how Nehru lived and what he did in his personal life—you are not judging a medieval prophet or a religious saint—but what is the impact of his action and policy on the course of Indian history. His personal life matters only if it is correlative to his political action.

Or take the example of M.N. Roy’s characterisation of Nehru as one who rationalised the irrationalism of Gandhi. “Nehru’s morbid anti-British animus,” wrote M.N. Roy, “is a psycho-pathological phenomenon; it is a form of masochism. In his adolescence, Nehru came under influence of modernism. His entire political life is a protest and an attempted atonement against that fall from grace.””

I don’t want to say anything about the quality of M.N. Roy’s modernism. But the fact of history is that Nehru’s modernism mattered and M.N. Roy’s did not.

It is important for the Indian socialists to try to understand why Nehru mattered, why he was so effective in the development of socialism in India in spite of his class roots, his vacillations, his liberty from the discipline of socialist thought.

Nehru as an individual has to be set against the currents of history to anaylse how far Nehru’s personality or particular historical circumstances contributed to the significance of Nehru’s role in contemporary history. One cannot avoid dealing with these questions, simply because perfectly convincing answers cannot be given to them, especially as they involve very recent history.

Some attempt has to be made to offer some answers howsoever incomplete or partial they may be, if only to provoke controversy and further discussion.

Freshness of Approach

IT is difficult to accept that Nehru’s importance was derived from his position as a theoretician of socialism in the Congress. No doubt that Nehru’s writings often had an inspiring quality and on occasions demonstrated some freshness of approach and novelty of ideas.

But his discussions on socialism, even when they displayed a striking sense of realism, lacked any framework of a consistent philosophy. He was not a Marxist, though some of his writings and speeches, especially during the thirties, showed some understanding, or rather awareness of the Marxian categories.

It is possible to provide a long list of quotations from his writings and speeches which contradicts the accepted Marxian conception of the socialist movement. He was more of a “subjectivist socialist”, a term that Lenin used to characterise Sun-yat Sen.

His socialism was more a system of just social order, where the accent was more on the individual and his freedom and the social order was to be reorganised to allow the individual to maximise his happiness. He would happily subscribe to utilitarianism, if that philosophy could make a more comfortable adjustment with the conditions of the modern economy.

Marxian Approach

THE Marxian approach to socialism is based on a philosophy of history where the social order changes as the process of historical progress reveals itself through the dialectical relationship between the means of production and production relations. Socialism here emerges out of capitalism as an objective necessity, not because some people will it as a better and just social order, although once it is established it does prove to be so.

But there is another approach to socialism which is quite rational, where a socialist makes his value judgment explicit at the very outset and declares his preference for socialism defined in terms of socio-economic categories. Socialism may be desirable because it is a rational, just, equitable and least wasteful social order, and in an underdeveloped economy in addition to all these because it is most helpful for rapid economic progress, and not simply because it is the “necessary” outcome of a historical process.

Having accepted socialism as a preferred system, one has to think of the best means for achieving it and for that one has to study objectively the prevailing economic and social conditions, the role of different classes, their relationships and conflicts, the stage of development of production forces, etc.

Insofar as revolution, violence, intensification of class conflicts, or alliance with some classes against others are considered as means to an end rather than an end in itself, it is difficult to see why the methods of the socialists of the second kind and of the Marxian variety, if both are based on ‘concrete’ study of ‘concrete’ conditions, should have much different impact on the development of socialism.

Logically one should be able to reduce the differences in the method of these two kinds of socialists to their differences in the understanding of the objective conditions of the society and it is by no means true that the orthodox Marxian understanding of social conditions has been always correct.

Consequently, a method that is based on a more ‘correct’ understanding of the social and economic conditions can make a very effective contribution to the development of socialism, no matter whether this method is applied by people whose orientation towards socialism is ‘subjective’ or Marxist or otherwise.

Jawaharlal Nehru’s orientation forwards socialism was not Marxist, but on many occasions he demonstrated a better understanding of the objective conditions of the Indian society than the Marxists or other socialists and hence played a much more effective role in the development of socialism in India than others.

Inconsistencies

THERE is much evidence of his superior understanding in his speeches and writings, but as he was not a very good theoretician disciplined in logical vigour, one might find some inconsistencies and vague or equivocal statements there. But it is his action and policy measures that more than anything else display his strong sense of realism, his remarkable understanding of the nature of social and economic forces in India.

Take the example of the importance and force of nationalism, a phenomenon that Marxists could never comfortably incorporate into their system. That such an ideal, which is, according to their categories, an essentially bourgeois value, can have a tremendous influence on the masses of people and rouse all sections of them to revolutionary action is something that never ceased to surprise them.

The Communist International and the League Against Imperialism tried to size up the national liberation movements of the colonies as a part of the unfolding world revolution and since the object of the latter was socialism and since socialism could be achieved only by the working class, a whole lot of Marxists in the colonies refused to recognise any national movement led by classes other than the working class as genuine.

Miserable Isolation

THE result was a miserable isolation from the mainstream of mass movement, which paralysed the communist forces in most of the colonies. This was true, not only in India but also in Algeria, Egypt and even in Cuba. Nehru’s freedom from doctrinaire Marxism allowed him to embrace nationalism wholeheartedly. He was sure that nationalism was not enough and that it was the first step towards socialism.

“Socialism is… for me not merely an economic doctrine which I favour; it is a vital creed which I hold with all my head and heart. I work for Indian independence because the nationalist in me cannot tolerate alien domination; I work for it even more because for me it is the inevitable step to social and economic change.”

Thus Nehru tried to associate nationalism with socialism, to show in speeches and writings (Whither India is an excellent example for that) that the goals of national independence cannot be fully realised unless they are combined with socialism. Curiously enough this led M.N. Roy, probably the most articulate Marxist at that time, to discover Fascistic tendencies in Nehru apparently because Fascism in Europe chose to call itself National Socialism!

Nehru had no illusions that the nationalist movement in India was led by the working class. He wrote in 1936: “It should be remembered that the nationalist movement in India, like all nationalist movements, was essentially a bourgeois movement. It represented the natural historical stage of development, and to consider it or to criticise it as a working-class movement is wrong.”

Still he joined this movement because it was a step towards progress and because it was capable of representing interests of large sections of masses and inspiring them towards united struggle.

Evaluation of Gandhi

CLOSELY related to Nehru’s understanding of the importance of nationalism was his evaluation of Gandhi, where again the failure of Marxists and other Leftists was astounding. To paint Gandhi as an ally of imperialism or a mouthpiece of reaction, as many of the Leftists used to do, is, to say the least, a total failure to grasp the realities of the Indian movement for independence.

This was a mistake that no socialist could afford to make, for the primary task of a socialist was to understand the nature of the Indian movement if he wanted to channel it towards socialism. Declaring that the Congress under Gandhi’s leadership was a joint anti-imperialist front, Nehru wrote in reply to attacks on Gandhi by Soumyen Tagore in France:

“(The) main contribution of Gandhi to India and the Indian masses has been through the powerful movements which he launched through the National Congress. Through nationwide action he sought to mould the millions, and largely succeeded in doing so, and changing them from a demoralised, timid, and hopeless mass, bullied and crushed by every dominant interest, and incapable of resistence, into a people with self-respect and self-reliance, resisting tyranny and capable of united action and sacrifice for a larger cause.

“He made them think of political and economic issues, and every village and every bazaar hummed with argument and debate on the new ideas and hopes that filled the people. That was an amazing psychological change. The time was ripe for it, of course, and circumstances and world conditions worked for this change.

“But a great leader is necessary to take advantage of circumstances and conditions. Gandhi was that leader, and he released many of the bonds that imprisoned and disabled our mind, and none of us who experienced it can ever forget that great feeling of release and exhilaration that came out in Indian people.

“Gandhi has played a revolutionary role in India of the greatest importance because he knew how to make the most of the objective conditions and could reach the heart of the masses while groups with a more advanced ideology functioned largely in the air because they did not fit in with those conditions and could therefore not evoke any substantial response from the masses.”

Emotional Idolatry

THAT was a fine piece of writing. It contained some element of emotional idolatry, no doubt, but he definitely got the right point: that Gandhi’s accent on masses, his emphasis on mass participation in the national movement inevitably raised mass consciousness tremendously and made social issues vital.

Examples can be multiplied to demonstrate the superior understanding of the realities of India by Nehru compared to other Leftists and Marxists. I do not want to go into all of them here but I like to emphasise that this superior understanding was a crucial factor that made Nehru such an effective leader of Indian socialism. And this was true even more during the period after independence when Nehru’s contribution to the development of socialism in this country was most significant.

That political independence can be achieved prior to the realisation of economic independence and that it can be used as an effective instrument for achieving economic independence defied the rules of vulgar economic interpretation of history and during the early periods of independence many Leftists and socialists were loudly proclaiming that our independence was an illusion.

Nehru like other nationalists welcomed our political freedom but unlike most of them started working towards socialism, only through which, he thought, the country’s economic goals could be realised.

Nehru’s socialism, as I mentioned above, starts from the value of the individual and is integrally related to the democratic ideals. The totalitarian method was not acceptable to him simply because he was constitutionably incapable for it. His socialism had to be based on the parliamentary democratic method, through persuasion, understanding and educating the people.

But the fact that Nehru liked the democratic way or that he preferred persuasion to coercion as a method for realising socialism in India would not necessary make his method successful. Only if the objective conditions are favourable the application of a particular method can produce the desired effect, as it is a fact that some major objective factors did turn out to be favourable to Nehru’s method.

But besides this there was a big element of luck, or if one likes, historical accident, that helped Nehru. For Nehru was a poor political organiser, and whatever may be the method, parliamentary or non-parliamentary, achievement of socialism is necessarily dependent of a strong political organization that can carry the precepts of socialism into practice.

Fundamental Transformation

SOCIALISM, after all, involves a fundamental transformation of the society and a struggle against the forces of status quo deeply entrenched in the social organisation. Reliance on the state or administrative machinery and a bureaucracy, working within the bounds of legal institution cannot bring about a social revolution unless there is a strong sanction of mass movement behind it. A political organisation or a party has to enthuse the masses to socialist action, and unite the progressive sections in the struggle against the vested interests to enable the socialist policies to be implemented.

In a parliamentary system the importance of a strong socialist party is increased, for then in addition to being a vanguard organistion for determined action, it has to explain and justify its action to broad sections of the masses so that they can carry it into power.

The possibility of peaceful, parliamentary method of achieving socialism does not imply that the state or bureaucracy is neutral or autonomous, and that it can function independently of class struggle. On the contrary, for any implementation of a socialist policy, it can be effective only when it is aligned with the progressive classes and when a political party, which formalises and upholds the interests of these classes, organises them to united action.

Nehru’s failure to organise such a party will probably be regarded by the future historian as the greatest shortcoming of his career, and it is here, I think, that Nehru’s class roots, his upbringing, his mode of social existence had the most telling influence. Here again, Nehru epitomised the dilemma of the middle class intellectual practising politics in India. He was a misfit in our society.

His Western values, his rational approach to the world, his refusal to talk the language of revivalism, his inability to translate his ideas in terms of day-to-day experience of the common people, all created a gulf between him and the Indian people which he could never bridge. The people of India held him in awe and often also loved him, but seldom understood him. And such a person cannot build up a mass organisation.

Nehru’s leadership of the Indian National Congress was very largely a historical accident. Nehru represented a minority of young, modern Left-minded and vocal Congressmen, but the hard core of the Congress, its ideals, outlook and pattern of thinking were represented by Gandhi. It is a historical accident that Gandhi and Nehru formed a close personal relationship, for it is difficult to think of two more dissimilar personalities. Before independence, Nehru’s leadership was very much dependent on Gandhi’s support.

At least, it is safe to say that if Gandhi had opposed him, Nehru could hardly maintain his leadership. After independence, his leadership was very much aided by historical accidents of death and disappearance from the political scene of several important leaders who were opposed to Nehru’s views.

Bourgeois Party

BUT the Congress, as Nehru repeatedly mentioned, was never a party of the working class, although its elements, like other elements of the people, were represented in it since the days of the independence movement. It was mainly a bourgeois party, but Nehru could work through this party towards socialism because in this phase of Indian development the interests of the bourgeoisie and the working class and other progressive elements did not come into sharp conflict.

Nehru realised that industrialisation was the first necessary step towards socialism, and that in the initial phase of it the interests of the national bourgeoisie, who wanted an independent development of their market and accumulation of capital, were consistent with the interests of socialism. He only wanted to hasten the process of industrialisation by trying to raise the rate of growth and control its direction through planning and to maintain state command over the strategic sectors of the economy, which would grow in strength and coverage and ultimately absorb the whole system under socialism.

Qualitative Change

THE exact time when this qualitative change would occur, when the state through the increasing strength of the public sector would convert the economy to socialism, is still far off and Nehru did not live to see even the beginning of it. Meanwhile, Nehru recognised the national bourgeoisie as an ally of the socialist forces, and he chose to concentrate his attacks on forces that inhibited the march of progress. He singled out the feudal relationship in land as primarily responsible for poverty in agriculture that was in turn arresting the growth of industries, and communalism, provincialism and many other forms of superstitions as elements that were resisting the progress towards the consolidation of India and the dissemination of scientific values, both of which are essential pre-conditions for rapid industrialisation. In his speeches, writings and policies, he repeatedly identified these elements as the principal enemies of Indian development.

I do not claim that all of Nehru’s policies were successful, that he planted the roots of socialism in India deep enough so that it can now progress with its own momentum. But I ascribe his failures mainly to the failures of implementation of his policies and that was again very much due to the absence of a purposive mass movement supporting his socialist actions, and I believe much of the blame for this has to be shared by other socialist organisations.

Nehru had to depend only on the Congress organisation as he was not capable of forming an organisation himself. And no other oganisation recognised the heterogenous character of the Congress, as inherited from the pre-independence days and the need for strengthening the socialist forces that formed a transitional alliance with the bourgeiousie. No other party came out to support Nehru’s socialism and build up a mass movement to carry it out in practice. So Nehru had to work within the limitations of the organisation of the Congress and his measures met with only limited success.

But still, what Nehru has left behind to his followers in the path of socialism is by no means insignificant. A large industrial base has been created, industrial growth has been proceeding at a very high rate over the last decade, several commanding heights of the economy are controlled by the state, heavy and basic industries, which have developed fast and on whose control the direction of our development will largely depend, are mostly in the public sector, and besides all this, the idea of socialism has emerged as a vital force in India today.

It is true that forces against socialism have also become strong, the Indian bourgeoisie has passed its stage of infancy and the vested interests have become more organised. The future of Indian socialism will depend very much on what happens now, for from this position India may turn its back on socialism and develop along the capitalist path, or may stick to socialism and march towards the realisation of the ideals for which Nehru dedicated himself. The judgement of history on Nehru will also be a judgement on the forces of socialism in India today.

(Courtesy: Mainstream, November 14, 1964 and Mainstream, November 13, 2010.)