(Part 2 of a series on Nehru and the Non-Aligned Movement. Part 1 was published in the previous issue of Janata.)

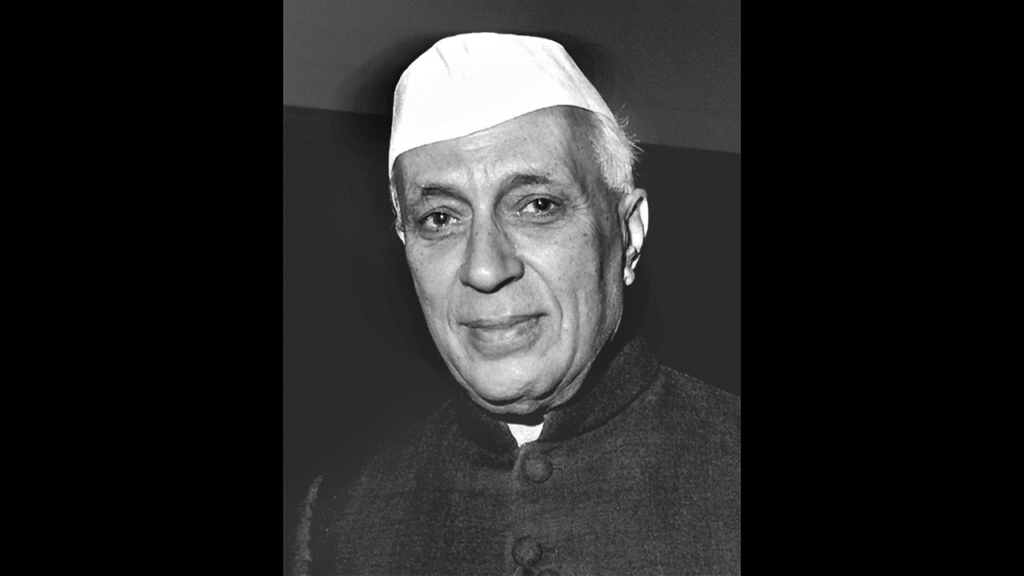

One development that had a significant bearing on shaping a non-aligned policy was Nehru’s visit to the United States in October 1949. The US administration timed the visit to coincide with the ascendancy of the Communist Party to power in China. According to Prof HW Brands of the University of Texas at Austin, US, “With the communist victory in China, Americans began to look on India with new eyes. In October 1949, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru visited the United States… Every major newspaper devoted editorials to the significance of Nehru’s visit; news-magazines and informed journals held forth on the enlarged role that India must now play in the world. Nehru arrived in the United States only days after the official proclamation of the People’s Republic of China; through nearly all the American commentary ran a single theme—China had fallen, India must not fall… The purpose of increasing the Western orientation of South Asia was to strengthen India and Pakistan against communism….”

During the visit, the US establishment exerted considerable pressure on Nehru to desist from recognising the People’s Republic of China and draw India into the anti-communist camp. However, Nehru spurned all US attempts to entangle India in a military alliance in return for the economic aid that Nehru had gone to seek. Nehru opted to return home empty-handed, without American assistance, rather than let India become a camp follower of the US establishment. Prof. Dennis Merrill, professor of history at the University of Missouri, US, recounted the outcome of that India-US meeting as follows, “When American officials concluded that India counted for little in terms of US foreign policy, they denied that nation’s request for economic aid.”

Only after India began receiving rice from China through barter trade was the US compelled to sell wheat to India. A page-six headline published on 2 January 1951 in The New York Times said, China to Sell India Rice; To Ship 50,000 Tons of Grain in Barter Deal for Jute appears to have completely rattled the US administration. Six weeks after this news emerged, the US President on 12 February 1951 recommended to the US Congress to provide India with two million tons of grain on loan. Yet, it took another three months before the US President formally signed the ‘India Emergency Food Aid Act, 1951’, on 15 June 1951. Meanwhile, both China and the Soviet Union had offered to sell more food grains to India. Also, Nehru made it clear on 1 May 1951 that “India, though grateful for help, would not accept food from any country if it had ‘any political strings attached’ to it”.

Positive Neutrality

Nehru was an ardent proponent of Positive Neutrality, which consisted of non-participation in military blocs combined with active moves against the conclusion of military alliances and promoting the cause of disarmament. It also entailed mediation in settlement of international disputes to ease international tensions. It meant firm opposition to colonialism and lending active support to all peoples fighting for independence. Integral to it was the struggle against apartheid and racialism expressed in the demand for complete equality of races and the banning of discrimination against any people. Positive neutrality manifested itself, above all, in the active campaign to preserve and strengthen world peace.

India and the Korean War

India was extremely concerned about the outbreak of violent hostilities between North and South Korea on 25 June 1950. After the US and its allies (masked as “UN forces”) entered the war on the side of South Korea on 13 July 1950, Nehru sent messages to the Soviet Union and the US stating that India aimed to “localise the conflict and assist the speedy, peaceful settlement”. Nehru suggested that the US, the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China, with the assistance of other states, “…find a basis for cessation of the conflict for a final solution of the Korean problem”. [Ref: Yuri Nasenko, “Jawaharlal Nehru and India’s Foreign Policy”, Sterling Publishers, 1977 p.106.] While the Soviet Union welcomed the proposal, the United States rejected it.

Concurrently, as news of American war crimes in North Korea due to widespread aerial bombings began to appear, protest movements in India against the US intervention grew, which even The New York Times could not help noticing. According to an NYT report, “Anti-United States feeling in India never has been so widespread as it is now. With every day of the Korean war bringing more news of bombed cities and flaming villages, the unpopularity of the United States is growing.”

After North Korean forces were pushed back from South Korea, it became evident that the “UN forces” were preparing to invade North Korea. The PRC informed India through the Indian Ambassador in China that it would be forced to enter the war if the “UN forces” cross the 38th parallel. To prevent escalation of the war, Nehru called a press conference on 30 September 1950 and fervently pleaded the “UN forces” not cross the 38th parallel. But the United States chose to ignore Nehru’s advice and invaded North Korea on 1 October 1950. As a result, China entered the war on the side of North Korea on 19 October 1950.

By late November 1950, Chinese and North Korean forces pushed the “UN forces” beyond the 38th parallel. Then in desperation, President Harry Truman even made veiled threats of using nuclear weapons against North Korea. After that, a series of attacks and counter-attacks took place until 11 April 1951, when General MacArthur, intent on escalating the war, was replaced as commander of the “UN forces” at the instance of US allies for insubordination. From then on until July 1953, other than a few sporadic violent incidents, the fighting practically stalled around the 38th parallel.

During 1951-1952, several attempts were made to arrive at a negotiated settlement. However, differences over the modalities to exchange prisoners of war persisted. On 17 November 1952, India proposed a neutral nations’ commission to resolve the issue, which the UN General Assembly accepted on 3 December 1952. It took seven more months before all concerned parties were brought on board to sign the truce in Korea on 27 July 1953. India was asked to head the neutral nation’s commission on repatriation of the prisoners of war and to provide security forces during the prisoners’ exchange.

Thus, according to historian Yuri Nasenko, a former professor of history, Patrice Lumumba People’s Friendship University, Moscow, “India deserves much credit for its efforts to secure a peaceful settlement in Korea and recognition of the fact that the Indian draft resolution formed the basis of the agreement on the prisoners of war which made it possible to lead the talks on Korea out of an impasse.”

‘Standstill Agreement’

Nehru was deeply perturbed by the series of atmospheric and underwater nuclear weapon tests being conducted by the then three nuclear-weapon states, namely, the US, USSR, and UK. Alarmed by the reported grievous impact of the atmospheric test of a hydrogen bomb conducted by the US over the Pacific Islands on 1 March 1954, Nehru expressed serious concerns in the Indian Parliament on 2 April 1954.

He said, “A new weapon of unprecedented power, both in volume and intensity, with unascertained, and probably unascertainable, range of destructive potential in respect of time and space, that is both as regards duration and extent of its consequences, is being tested, unleashing its massive power, for use as a weapon of war… We are told that there is no effective protection against the hydrogen bomb and that millions of people may be exterminated by a single explosion… These are horrible prospects, and it affects us, nations and peoples everywhere whether we are involved in wars or power blocs or not… [Hu]mankind has to awaken itself to the reality and face the situation with determination and assert itself to avert calamity… Pending progress towards some solution, full or partial, in respect of the prohibition and elimination of these weapons of mass destruction… the Government [of India] would consider, among steps to be taken now and forthwith, the following:

“Some sort of, what may be called, “Standstill Agreement” in respect, at least of these actual explosions, even if arrangements about the discontinuance of production and stockpiling must wait more substantial arrangements amongst those principally concerned….”

From Nehru’s point of view, disarmament in general and the elimination of nuclear weapons in particular, were integral to the doctrine of non-alignment.

(The author is joint secretary, Delhi Science Forum, and member, National Coordination Committee, Coalition for Nuclear Disarmament and Peace. Courtesy: Newsclick.)