A few days ago, a government-run website, knowindia.gov.in, deleted a paragraph that described the period of the Mughal empire as one of the “greatest” in history. The deletion followed objections raised on a public platform by pro-RSS ideologue and writer Ratan Sharda, who sought to vilify the Mughal era (16th-19th centuries) as cruel and unjust. It is part of the predictable pattern of majoritarian consolidation, wherein the Mughal rule is projected as Muslim rule to target present-day Indian Muslims with scorn, hate, and even violence.

A fresh look at the Mughal state and economy would repudiate this approach. Far from oppressing linguistic, religious and regional identities, the Mughals were, arguably, “nation-builders” of the pre-modern era. In Akbar’s period, by the mid-to-late 16th century, three modernistic political goals of a modern nation-state would crystallise. He unified a vast territory, minimised religious considerations in everyday life and governnace, and included multiple identities within an empire. Other Mughal rulers demonstrated plurality and inclusivity too. Indeed, an inclusivist and pluralist idea of India was first coherently articulated by the 13th-century Sufi-poet Amir Khusrau, as Prof Nadeem Rezavi describes elsewhere.

Even in the 15th century, some regional rulers such as Zainul Abedin of Kashmir and social movements like Kabir, Guru Nanak, and his followers in north India marked the shift towards a less unequal and more inclusive society and polity. These pre-existing trends found their profound articulation under Akbar.

Akhand Bharat versus Kaghazi Raj

One of the largest empires by sheer landmass, Mughal India was politically and administratively unified but allowed regional freedom and limited autonomy to specific regions. What today are India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and eastern Afghanistan, were Mughal provinces. Mirza Hakim, the governor of the outward territory of Afghanistan, was Akbar’s brother. It is this vast area, including India’s present-day landmass, that the RSS wants to reappropriate as Akhand Bharat. Ironically, it blames the Mughals who had unified these territories for the alleged splintering of Akhand Bharat. Wilfully ignoring the histories of social, political, and economic heterogeneities, the RSS has chosen divisiveness as the route to perpetuate myths about Islam and Muslims in India.

Historians would still say that the unique combination of civil and military institutions under the Mansabdari System, which Akbar’s successors slightly modified, was a robust and highly functional institution to administer India. For example, non-Muslim elites got constantly included as Mansabdars under successive Mughal rulers. Impressed with the meticulous contemporary paper records of the Mansabs, the historian Sir Jadunath Sarkar (1870-1958) called the Mughal empire a Kaghazi or paper Raj. He was not just referring to the well-kept royal memoirs. The Mughals recorded land holdings, economic activities, cultures, festivals, ways of life, and even instances of corruption, along with evidence.

Some credit for efficient record-keeping also goes to the theory of sovereignty developed by Abul Fazl, the court historian of Akbar. The Noor-e-Ilahi or light of god theory of kingship somewhat resembled Maryada Purushottam, the pre-existing notion of sovereignty in India. The administrative apparatus and principles combined people across an extensive empire, which was barely possible in the pre-modern era elsewhere in the world.

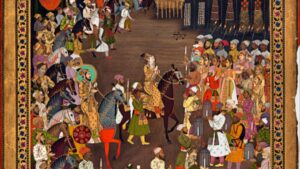

Akbar patronised the Persian rendering of Hindu religious texts Ramayana, Mahabharata (Razmnama), and others. In art and architecture of his period, we find decorative motifs and symbols of all Indian religions. The lotus (padma), elephant (gaja), swan (hamsa), swastika, chakra, bird, deer, fish, associated with Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Christianity and other faiths, are found in Mughal architecture and painting.

Aligarh-based art historian SP Varma researched Mughal-era literary evidence and paintings to demonstrate substantial participation by Mughal rulers and administrators in Hindu festivals such as Holi, Diwali, and Raksha Bandhan. There is evidence that every year Akbar spent a whole day getting Rakhis tied. Sanskrit flourished at the Mughal courts as it did in the pre-Mughal Muslim rulers’ courts. It is described in great detail by Aligarh-based historian Pushpa Prasad. Rutgers University historian Audrey Truschke also recently published a book on the theme.

Writers could express themselves in local and regional languages and share their creative works. Peasant-poet Kumbhan wrote in Braj bhasha: Sanatan ko kaha Sikri son kaam/ Sanatan ka Sikri se ka kaam/ Aaawat-jaat panhaiya tooti bisari gayo Hari naam/ Jinko mukh dekhe dukh upjat tin kahun kareyo pada salam.

Despite such defiant verses against the emperor at Fatehpur Sikri, Kumbhan did not get charged with sedition or punished for insult. Instead, the emperor offered him grants that the independent creative intellectual politely declined. He continued to defy the state in his works. Music found a lot of patronage too. Tansen (Ramtanu Pandey) was not the only musician who was patronised. (Katherine Schofield of Kings’ College London has written biographies of the court musicians.)

Tulsidas wrote the Ramcharitmaanas in Awadhi from Ayodhya. In essence, the life of the general people went on without fear of the state. Each knew his place in the social hierarchy, as we must not confuse this with the post-Enlightenment era. There was competition and conflict, especially in the higher echelons, over the fruits of position and power. It reflected, for example, in the Jagirdari crisis that threatened the empire in the 18th century, long after the era of the great Mughals.

Late Mughals and colonial India

Even in the late-Mughal era, the earlier administrative models, institutions, administrative terminologies prevailed. These models were emulated and endured in the regional kingdoms. Mughal political conflicts with regional powers such as Akbar with Rana Pratap, or Aurangzeb’s with Shivaji did not acquire the character of Hindu-Muslim conflicts. During the colonial era, writers such as James Mill, HM Elliot and Christopher Dowson started commenting on Indian politics in divisive terms. They periodicised Indian history cunningly, referring to the ancient period as the “Hindu period” and the medieval era as the Muslim period. (Of course, they never called the British period Christian rule!) In doing so, the colonial record-keepers and historians ignored the varied personal faith of the rulers and their military commanders and their armies.

Even today, government textbooks in India and history-based literary stories for schoolchildren do not emphasise these points enough. It is one reason why right-wing propagandists could get a toehold, especially in recent decades, and unleash animosities amongst the public.

In their thick travelogues, contemporary European travellers record that Mughal Indian cities were bigger than the cities of England or France. These were a consequence of wide-ranging production and trade activities. Mughal administrators brought newer varieties and more cash crops under cultivation, and the acreage expanded, thanks also to the expansive land revenue administration of Raja Todar Mal. Territorial and occupational mobility of the artisans helped rescue them from economic dependence. The karkhana system developed, wherein rulers or private business people, including administrators, owned the means of production.

Under the Mughals, India was moving towards capitalistic development with monetary and currency policies and hundis (bills of exchange), sarrafs (bankers), and insurers. European travellers testify that merchants of Mughal India such as Virji Vohra and Abdul Ghafur Bohra, both from Surat, had six to eight million rupees each by 1663. Manrique de Guzman (1630) was “amazed by the immense wealth of the merchants of Agra where piled up money looked like grain heaps”.

Irfan Habib demonstrates in his 1969 essay, “Potentialities of Capitalistic Development in India,” that of the four critical prerequisites for modern capitalistic development, Mughal India fulfilled at least three. These are the control of capital over the production process, money or market relations and immense accumulation of commodities. Only the fourth prerequisite, that is, a breakthrough in production technology, was missing.

The historian Ahsan Jan Qaisar (1929-2011) explained a cultural factor for this limitation as an “exposure response syndrome”. Through marvellous research, he shows that building construction technology advanced tremendously during the Mughal era. The epitome of Indian accomplishment in civil engineering endures as the Taj Mahal of Agra, not to mention the numerous other buildings and gardens. Yet there were limitations in shipbuilding technology and undertaking sea trade, which, if present, would have diversified the economy and reduced the burden on the agriculture sector. It may even have helped achieve breakthroughs in military technology. In turn, that may have contained the European advancements made during the 18th century.

That said, history does not look into the “what might have happened” kind of thing. One question is whether the impediment in seafaring had to do with the Surat Plunder of January 1664, in which the Marathas defeated the Mughals in a land battle. Historian RP Tripathi was exploring this subject but never completed his work before he passed away.

Indeed, the lack of technological breakthrough and the disintegration of the Mughal central authority into rival regional powers in the 18th century were the two main reasons why India succumbed to European powers. Again, this overturns the modern-day RSS charge that the Muslim rulers were colonisers. Importantly, it is the influential traders who, having made their riches from the Mughals and regional rulers, aligned with the European trading companies and facilitated the colonial subjugation of India. Therefore we see a shift in the polity as well, and 18th-century India had many a peasant rebellion against the state, which itself was under pressure from powerful trading classes and bankers. The regional powers were, however, oblivious of the alignment of merchant bankers with European trading companies.

If Akbar represented catholicity, inter-faith dialogue and tolerance, justice was elevated to the level of folklore during Jahangir’s rule from 1605-1627. The Adal-e-Jahangiri reverberated in theatres and plays. An instance from the reign of Shah Jahan is worth mentioning. A man from Gujarat approached him with the complaint that a mosque had been built on his property without permission. Shah Jahan delivered an immediate verdict to restore the property to the aggrieved complainant.

Symbol of authority

Even at its weakest moment, the central Mughal authority was, not for no reason, a very potent symbol. Most regional powers could not disregard its value. That is why during the 1857 rebellion, they rallied behind this symbol. Having smashed and overpowered it, the British set out to liquidate each direct descendent of the last Mughal to prevent it from staging a comeback.

In short, by pre-Modern standards, the Mughal empire was largely non-partisan and led a robust administration that created economic opportunities and was administratively varied. The state facilitated religious-cultural efflorescence through inclusive literary and cultural policies. The Mughal Indian state and society had features that resembled pluralistic and inclusive nation-building.

Informed and critical evaluation of the past is welcome, but motivated hate against Muslim communities simply because, centuries ago, rulers professed the same faith is probably clinical morbidity. No country with such a long and multi-coloured civilisational history can afford to ignore historical facts.

(The author is professor, Modern and Contemporary Indian History, Aligarh Muslim University. Courtesy: Newsclick.)