The Andaman and Nicobar Islands, jointly administered as a Union Territory of India, form two lush green archipelagos in the Indian Ocean, south of Myanmar and west of Thailand and Malaysia. The NITI Aayog, the Indian government’s top public-policy think tank, has since 2019 promoted a pair of development mega-projects here which promise to transform – or devastate – the southernmost islands in each chain, Little Andaman and Great Nicobar.

Little Andaman was first in the NITI Aayog’s sights, but the think tank’s mega-project for that island appears to have been suspended since 2021, with news updates on the project trickling out and without any formal announcement or explanation. Instead, the project on Great Nicobar Island – with an international container vessel transshipment port, and a new city and airport – has been “fast-tracked”, with construction bids underway as of April 2023 (although construction has been temporarily halted due to a case before the National Green Tribunal). The NITI Aayog and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Integrated Development Corporation, a body formed to execute the projects, have shunned transparency on the funding sources for the work, but the Great Nicobar scheme has been estimated to cost 720 billion Indian rupees, or nearly USD 9 billion.

These mega-projects have already challenged the land rights of the Onge, Shompen and Nicobarese indigenous people, seen a major sea turtle sanctuary denotified and set in motion a “compensatory” bait-and-switch involving a jungle safari park 2400 kilometres away. Despite urgent warnings of further environmental damage, seismic risks and dire human-rights implications, the NITI Aayog is plunging ahead with its plans to commercialise, industrialise and militarise the islands’ coastlines, reefs and forests.

Big “development” on Little Andaman

The Onges of Little Andaman are one of the several distinct groups of surviving indigenous peoples of the Andaman Islands. DNA studies estimate the arrival of their ancestors on the islands to date to around 18,000 years ago.

Unlike the still largely uncontacted Sentinelese to their north in the Andaman archipelago (who in 2018 killed an American attempting to evangelise them), the Onges are all too familiar with schemes to assimilate, modernise or exploit them. For centuries, Onges fiercely fended off slave traders and raided wrecked ships that came to be in their waters. In 1901, the Onge population was estimated at around 625 people. In the 1960s and 1970s, Indian government agents took charge of Little Andaman and began bringing over settlers from mainland India. As of the country’s 2011 census, the total population of Little Andaman was roughly 19,000.

After the 2004 tsunami, the government moved the Onges to reserves where they were housed in asbestos-roofed wooden cabins. As I wrote in my 2014 book, The Wind in the Bamboo, which looked at the past and present of indigenous Asian peoples categorised by scientific racism as “Negritos”, the Onges “suffered captivity depression, sexual abuse by Government workers, and alcohol dependence when they were confined to the two reserves on separate ends of the island.” Now, the Onge population numbers only about 125 people.

The NITI Aayog was founded in 2015 under India’s current prime minister, Narendra Modi, as a replacement for the Planning Commission, the Indian government’s main planning organ since the 1950s. In January 2021, a NITI Aayog ‘Vision Document’ describing the development of mega-projects for the Andaman and Nicobar Islands was revealed in the press. Like with pretty much every government or business document that has ever had the word “vision” in its title, the NITI Aayog’s plans were self-justifying and speculative. The document proposed that “Little Andaman: The Perfect Paradise” should be developed “to compete with global cities like Hong Kong, Singapore or Dubai.” The island would sprout an “Aerocity,” a “Medicity” and a financial district with a “Plug & Play office Complex.”

In addition to a new international airport, there would be a second airstrip “for private and direct access to the Super Luxurious Forest resorts.” Leisure pursuits might include an “Underwater Safari,” a “Wildlife Safari” and even a “River Safari” – although there is no river on the island. This, and the mention of nonexistent “mountains” – Little Andaman has a maximum elevation of 183 metres – indicated that the report’s authors had likely never so much as been to the island.

The NITI Aayog report’s section titled “Investment Potential: Entertainment” was illustrated with a photo of scantily dressed persons interacting with male tourists on Bangkok’s notorious Soi Cowboy, with the distinctive neon sign of The Dollhouse bar and a child flower-seller clearly visible. Suddenly, the vision was not Singapore anymore. On the other end of the respectability scale, a section on “Healthcare & Wellness” used a photo of the entrance to the Mayo Clinic, in the United States.

The NITI Aayog’s introduction to its report stated, “The presence of indigenous tribes and concerns for their welfare has been a key factor challenging island development.” Describing the Onges as a “primitive tribal group”, the ‘Vision Document’ listed the “presence of the Tribal Reserve” as a “key constraint” to be overcome. “If required, the tribals can be relocated to other parts of [the] island,” it casually suggested.

In February 2021, the NITI Aayog requested that 7733 square kilometres of land in the Onge Tribal Reserve be “denotified” – that is, to be cut out from the reserve and stripped of protected status – to enable “Phase I” development. This was accompanied with a comment that the Onges’ “traditional lifestyles are out of step with the march of history.” The NITI Aayog also planned to request the denotification of an additional 138 square kilometres of land and to acquire 22 square kilometres of the Onges’ offshore tribal reserve – amounting to 57 percent of its total area.

The NITI Aayog’s view of the Onge perpetuates a terrible legacy of outsiders considering them to be “primitive”, “Paleolithic” and the even more pejorative “savages”. This dates to at least the colonial period, but the end of colonialism has done nothing to change the Indian state’s view. The islands’ Black Indigenous Asians are widely assumed to be relics of the distant past and have been treated, literally, as attractions in a human safari, with buses full of gawping outsiders rolling through indigenous reserves. Their choices about contact with the outside world have always been, and continue to be, conveniently ignored.

In 2007, while researching The Wind in the Bamboo, I put my history books and DNA-science papers aside to visit the Andaman Islands. There, I met Samir Acharya, a legendary troublemaker who had defeated the islands’ logging industry. His Society for Andaman and Nicobar Ecology championed the land rights of the Onges and the Jarawas, another local indigenous people.

On Little Andaman, I caught a bus to a beach called Butler Bay, where green parakeets sparkled in the trees and a few Aussie surfers were camped near a “world-class left-hand break.” Nearby, two local men, one an Onge, were at work carrying wooden posts. Butler Bay is the location for the proposed Financial District and Aerocity in the alternate reality of the NITI Aayog’s ‘Vision Document’. This was part of the first portion of the Onge Tribal Reserve that the NITI Aayog sought to denotify in February 2021.

Consultation with the Onges and settlers of Little Andaman was conspicuously missing from the NITI Aayog’s plans. This fit a long-standing pattern: rather than listening to the islanders, Indian government officials have long served as gatekeepers preventing the Onges and others from complaining to outsiders. The Onge reserve at Dugong Creek lacks cellphone service and in-person access is tightly controlled. Sophie Grig of Survival International, an organisation that advocates for the rights of indigenous Andaman islanders, told me, “It would appear that the free, prior and informed consent of the Onge was neither sought nor given for this change to their reserve. This is a violation of their rights under international law.”

The NITI Aayog’s denotification effort in Little Andaman may have set a precedent for other official dealings with indigenous peoples of the Andaman Islands – including the Jarawas, who constantly have to deal with encroachment on their lands, and even the Sentinelese, who continue to defend themselves against outsiders. The approach seems to involve treating them as obstructions to progress, as historical relics without a say in the future of their islands, to be uprooted and displaced at will.

“Singapore” on Great Nicobar

The NITI Aayog has not moved forward with its Little Andaman project since 2021. Instead, by early 2022, it pivoted to activating its plan for a transshipment port designed to host massive container vessels on Great Nicobar – the largest island in the Nicobars, currently sparsely populated and thickly forested across its 921 square kilometres. Despite the improbability of this new port being able to compete with regional transshipment behemoths such as Singapore, Port Klang in Malaysia and Colombo in Sri Lanka, or even with new port facilities on the Indian mainland, the NITI Aayog is pressing ahead. Its “new Singapore” dream for Great Nicobar includes not just the port, but also a sprawling city, power plants and an airport.

The new airport would be partly for military use, tying the whole project to national security. This aspect has been used to justify secrecy about deforestation related to the planned airport. An Indian Air Force base already exists on another island of the archipelago, Car Nicobar, and the Nicobars have navy port facilities.

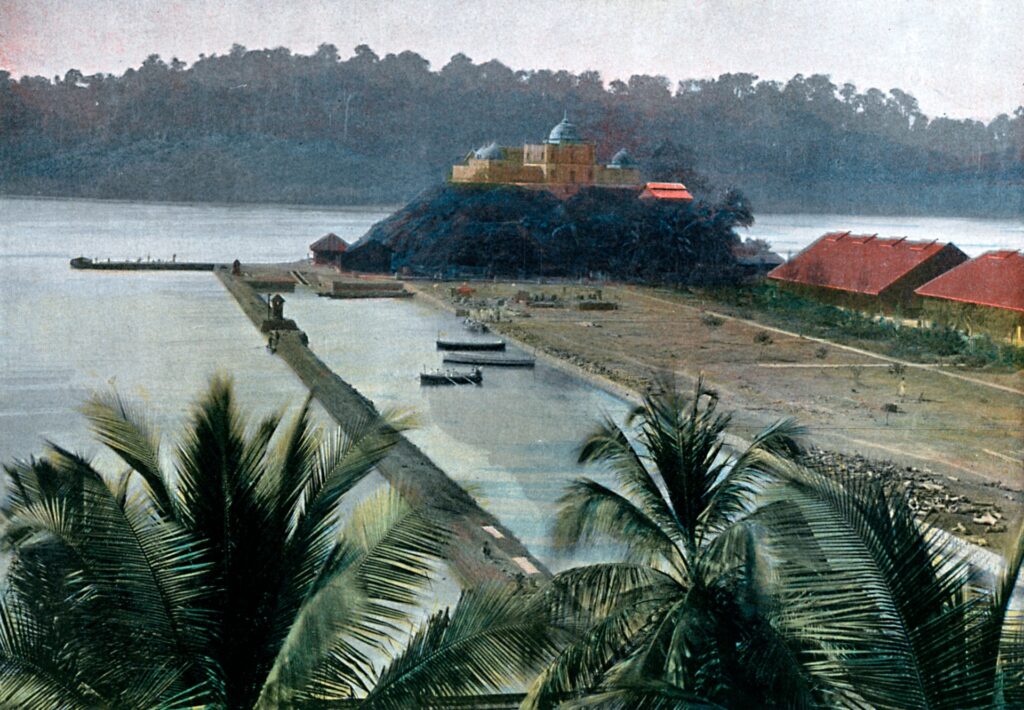

A shipping stopover during British colonial times, the Nicobars have been largely closed to outside commercial ventures since India gained independence, with the aim of protecting the indigenous people. Even so, there was earlier some rubber cultivation on the islands and resettlement of people from mainland India. From 1956 to 2018, both international and domestic tourists were barred from the Nicobar Islands. But now, as with the NITI Aayog’s proposal for Little Andaman, the disruptive Great Nicobar scheme envisions infrastructure for mass tourism on the island.

The NITI Aayog’s proposed transshipment port and new city are placed squarely in a zone with significant tsunami and earthquake dangers. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami hit the Nicobars severely, killing thousands. Great Nicobar, located along an active subduction system and near multiple geological fault lines, is very seismically unstable, with an average of 44 earthquakes per year. Writing about the project in Frontline in January 2023, the scientists Janki Andharia, V Ramesh and Ravinder Dhiman noted, “Following building codes is one thing, but going ahead and building on a fault line is reckless.” Great Nicobar is also extremely vulnerable to cyclonic storms exacerbated by the global climate crisis, as well as to rising sea levels.

The indigenous peoples of the Nicobar Islands are the Nicobarese and Shompens. Of Great Nicobar’s population of approximately 8500 people, about a thousand are Nicobarese and an estimated 245 are Shompens, with the rest being settlers from mainland India and their descendants. The Nicobarese, who live on several islands in the archipelago, speak Austroasiatic languages. Their culture includes traditional domed-thatch “beehive” houses, carved effigies and a form of Christian–Animist syncretism.

The reclusive people known to outsiders as Shompens live only on Great Nicobar, speak their own language and are primarily forest foragers. The hilly inland region they roam is delineated by several rivers and streams. Like the indigenous peoples of the Andamans (to whom they are not related), Shompens have been derided as marauding “savages”. They limit contact with outsiders and are considered forest guardians by the Nicobarese, who traditionally ask their permission before felling trees. Parts of the island where the Shompens currently live are included in a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

After the 2004 tsunami, many Nicobarese were relocated from their villages by the government as part of relief operations. Despite repeated requests to re-inhabit their original land, they were never allowed to return. A few Shompens were also relocated with the Nicobarese, among them a young man named Kakein who, removed from his culture and language group, took his own life in 2018. A group of anthropologists and other experts made a short film about Great Nicobar in 2019, in which one anthropologist asked a Shompen man for his response to “development”. His reply was, “Do not come near our hills. Do not clear hills. Do not climb our hills.”

The Nicobarese and coastal settlers of Great Nicobar have long expressed a desire for basic improvements in healthcare, education and inter-island connectivity. What they have not been asking for is mass tourism or development mega-projects. In 2022, representatives of relocated Nicobarese and Shompens yet again sent formal appeals to the government for the return of their lands and decried the deterioration of their health and culture due to prolonged displacement. The researcher Ajay Saini, writing in Frontline, quoted a displaced Nicobarese, Paul Joora: “We miss our villages, but they will also be missing us.”

E A S Sarma, a retired Indian government official, has sent several letters of concern to government agencies in recent years, stressing the need to protect the Nicobarese and Shompens and pointing out that the latter are officially designated as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group. Sarma has noted that the project intends to eventually settle 350,000 people on Great Nicobar, a “huge influx of outsiders, whose presence would impact the Tribal Reserve and hurt the interests of the local tribal groups.” Most of Great Nicobar is a designated tribal reserve.

The Andaman and Nicobar government initially gained a No Objection Certificate for the NITI Aayog project from the Tribal Council of Great Nicobar. This was done in August 2022, but within months the Tribal Council withdrew its consent, stating that it had been misled about the project’s diversion of a swathe of ancestral domain lands, which were to be treated as “vacant” for the purposes of the project. “We express our strong disagreement to this decision and demand that the forest clearance and the denotification of our Tribal Reserve be revoked,” the council’s letter of withdrawal said. Ajay Saini quoted a Nicobarese village leader: “They lied to us in the public hearing. The project will eat several of our pre-tsunami villages.”

Damage done

Great Nicobar’s Galathea Bay Wildlife Sanctuary is a crucial nesting area for leatherback sea turtles. The highly biodiverse island is also the habitat of Nicobar long-tailed macaques, Nicobar treeshrews, Nicobar scops owls, Nicobar pigeons, and a large bird called the Nicobar megapode. Now, these species and more are in jeopardy from the immense footprint of the NITI Aayog’s mega-project.

To make way for the port, in early 2021 the NITI Aayog was able to have the Galathea Bay Wildlife Sanctuary denotified by India’s Standing Committee of the National Board for Wildlife. This was accompanied by ineffectual suggestions for mitigation of the environmental impact, such as the use of “Ecological Marker Buoys.” If the project comes to fruition, Galathea Bay’s nesting beaches, used by hundreds of leatherback turtles, would be irremediably blocked by piers and breakwaters. The marine environment surrounding Great Nicobar would also be disrupted by the arrival of massive container ships. In addition, construction of the port and city, intended to stretch over decades and consume the island’s entire southeast coast, would also destroy mangrove forests and coral reefs that act as essential storm barriers.

As per procedure, the NITI Aayog commissioned an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) on the project from a consulting firm, Vimta Labs. In 2022, Vimta produced a brief report in favour of the project. Among many other flaws, this EIA underreported the extent of Great Nicobar’s Tribal Reserve Area by over 100 square kilometres. Confusingly, Vimta’s EIA generally used “Nicobaries” to refer to islanders of all ethnicities, but also frequently used “Nicobaries” to refer specifically to the Nicobarese indigenous people. The document stated in one place that on Great Nicobar the “total Nicobaries Population is 860 and household are 230”, but asserted elsewhere of the Nicobarese and Shompens that “their present population is 1094 and 237 respectively.”

The EIA was padded out with ethnographic descriptions of the Shompens and Nicobarese lifted nearly verbatim from Wikipedia pages. It also included numerous pieces of outdated or misleading information. For instance, the document stated that the “Nicobarese are headed by a chief called ‘Rani’ or ‘queen’”, which is not the case in Great Nicobar, and that “No agriculture is being practiced” by “Nicobaries”, ignoring their orchards and vegetable farms.

Vimta’s EIA featured a frightening depiction of the island’s topography and ecosystems: “The hills are steep, slippery and totally covered by multi-storeyed vegetation. Whenever we could gain entry through some opening into the dense/thick forest, visibility was poor; humidity was high; soil was wet and slippery … Added to the problem was biting insects including mosquitoes.” The document also called Great Nicobar’s long-tailed macaques, a vulnerable subspecies, a “menace”, and advised relocating them to other islands. The EIA also suggested relocating crocodiles from the project area.

It also asserted, “The western flank of the Galathea beach where the leatherback turtle nests, is about 1.5 km from the edge of the power plant boundary and is separated by sporadic dense for [sic] forest and riverine vegetation. Therefore, the power plant construction will have no deleterious impact on the nesting of the leatherback turtles.” This showed a stunning disregard for the fragility of sea turtle nesting sites, which are vulnerable to erosion and disruption of access as well as noise and light pollution.

In October 2022, the Indian government’s Forest Advisory Committee approved the obliteration of 130 square kilometres of primary forest on Great Nicobar for the project, conditional on “compensatory afforestation.” Astoundingly, this was to occur 2400 kilometres away in Haryana, on the Indian mainland, in the form of a new “jungle” zoo, billed as “the world’s largest curated safari.”

The NITI Aayog, India’s Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways, and Vimta Labs had not responded to emailed questions about the development projects at the time this article was published.

Environmentalists have challenged the NITI Aayog’s Great Nicobar project before India’s National Green Tribunal. In April 2023, the tribunal ruled that the project “does not call for interference” as it has “great significance not only for economic development of the island and surrounding areas of strategic location but also for defence and national security.”

The tribunal placed a temporary hold on “irreversible” steps involving “environmental clearance” for the project so a special committee could examine its effects on coral reefs, the possible insufficiencies in its impact assessments, and the very notion of building a port in an official Coastal Regulation Zone where construction is not allowed. But this committee did not appear independent or impartial, as it was to include one member nominated by India’s Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways, another selected by the NITI Aayog and others from bodies which have already given their support to the project.

Indian journalists, academics, scientists and activists who care deeply about the Andaman and Nicobar Islands have been sounding alarms about the NITI Aayog’s plans for many years now. A few politicians have joined them, but not enough to overcome the fortress mentality or at-all-costs approach to “development” that characterises the government of Narendra Modi. Access to the Nicobarese to gauge their opinions is very limited, and this is even more the case for the Onges and Shompens, whose protective isolation ironically deprives them of a say in the disposal of their islands.

The NITI Aayog was close-mouthed throughout the process of obtaining the necessary permissions for the project, and even denied the existence of its original ‘Vision Document’ in response to Right to Information applications. The Great Nicobar port project is now moving forward under the watch of Sarbananda Sonowal, India’s minister for ports, shipping and waterways. In March 2023, he told the Business Standard, “We have no second thoughts on the project. The expression of interest round has been completed, and several parties have shown interest. It is true that different stakeholders have raised environmental concerns, but those have been clearly addressed.” The Nicobar Times, a digital publication that has been supportive of the project, has claimed that the expressions of interest submitted by ten companies for Phase I of the port project were “a tight slap on the rumour mongers and haters” standing against the project, and has also labeled the opposition to the port a “smear campaign.”

Even if the NITI Aayog’s grandest plans never materialise, immense and irremediable damage can be done just by Phase I preparations. This includes deforestation, pollution, habitat disruption, loss of ancestral land rights and more. It will take grim determination, relentless legal action and massive amplification of islanders’ opposition to the NITI Aayog’s plans to defeat the Indian government’s mega-projects before they cause enormous environmental, social and cultural ruin in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

(Edith Mirante is the author of ‘The Wind in the Bamboo’ about Black Indigenous Asians including Andaman Islanders. She has written for Himal Southasian on Myanmar’s coal and jade mining. Courtesy: Himal Southasian, an independent, non-nationalist, pan-subcontinental magazine. It is Southasia’s first and only regional magazine of politics and culture.)