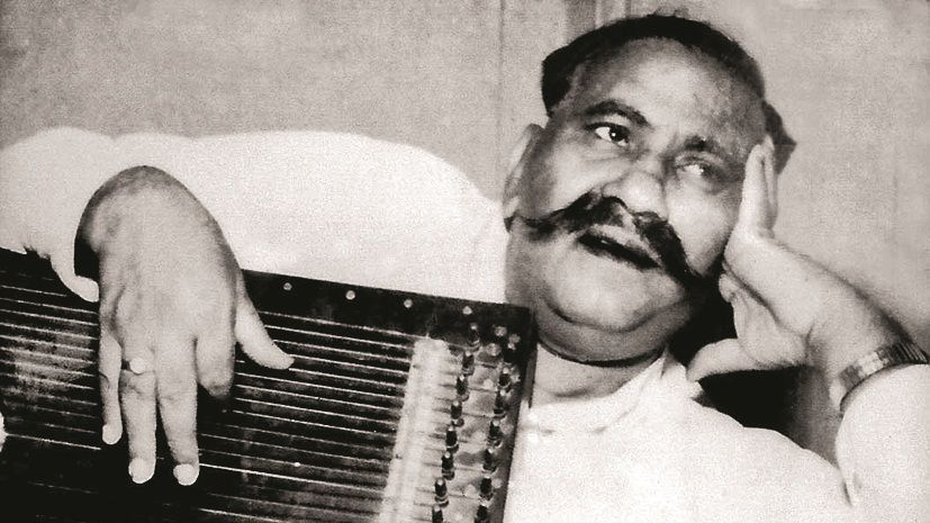

Ramachandra Guha

Most evenings, I knock off from work and listen to Indian classical music for an hour or so before dinner. In the past, I would play CDs or cassettes I had collected over the years; now, I forage through the capacious repository that is YouTube. Sometimes I select an artist or a particular raga; at other times, I go with the algorithm that is given to me (based I presume on my past record). A few weeks ago, YouTube threw up, at the top of its list, a rendering of the Raga Hamsadhvani by Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. I obediently followed the orders issued to me, and listened to the rendition. And then I listened to it again. And again.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan was born in 1902 in Kasur, in west Punjab. His father, Ali Baksh, was a singer of the Patiala gharana, patronized by the Sikh maharajas of that princely state. After Partition, Bade Ghulam chose to move to Pakistan, but, finding the audience for classical music limited (in all senses of the word), wished to return to the Indian side of the border. In the 1950s, it was much easier to travel between these two countries than it is now. So Bade Ghulam made a trip to Mumbai, where someone brought his predicament to the attention of Morarji Desai, then the chief minister of the undivided Bombay State. Morarji bhai arranged for a government house for the maestro, while the Central government, headed at the time by Jawaharlal Nehru, smoothed the way for this Muslim from Pakistan to become a citizen of India.

Hamsadhvani is a lovely, melodious, raga in the Carnatic tradition, said to have been originally composed by Ramaswamy Dikshitar in the 18th century. There are many songs set in this raga, such as “Vatapi Ganapathim”, a hugely popular item in the repertoire of (among others) M.S. Subbulakshmi and M.L. Vasanthakumari. At some stage the raga was also adapted by Hindustani musicians for their own use.

I myself listen much more to Hindustani than to Carnatic music. I had heard, many times, Hamsadhvani as rendered by the vocalists, Amir Khan and Kishori Amonkar, and by the flautist, Panna Lal Ghosh. But this was the first time I had heard it sung by Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, whom I had previously known (and loved) for his renditions of Pahadi and Behag. I checked with a more learned friend, and found that my hunch was correct; that Bade Ghulam rarely sang Hamsadhvani, and this was therefore a very special recording.

Digging deeper into YouTube, I discovered, to my great delight, that this particular rendition of Hamsadhvani was from a concert that Bade Ghulam Ali Khan had given in my home town, Bangalore, in 1956. The concert was part of the Rama Navami festival, then (as now) an important part of the city’s musical calendar, and held always in the capacious grounds of the Fort High School in Chamarajpet.

The ‘Fort’, after which this High School is named, was originally a mud structure, built by Kempegowda in the 16th century. It was later rebuilt in stone by Hyder Ali, and further embellished by Hyder’s son, Tipu, in the 18th century. However, the school itself dates to the early 20th century, and its building, a very handsome one, is constructed in the British colonial style.

These further details enchanted me. For, in recent years, I have sometimes attended concerts at the Rama Navami festival myself. I was not born in 1956; but it is entirely likely that among those who heard Bade Ghulam sing there that year were people I was to later come to know, such the celebrated Bangalore rasikas, Shivaram and Lalitha Ubhayaker. I like to think (or hope) that also in the audience that day was the legendary physicist, C.V. Raman, who had a keen interest in classical music. Perhaps some uncles and aunts of mine who lived in Chamarajpet were in attendance too.

So here was Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, singing Hamsadhvani at the Ram Navami festival, held annually at the Fort High School in Bangalore. A Muslim musician in India, born in what is now Pakistan. An acclaimed ustad of a gharana of Hindustani music patronized by Sikh maharajas. Singing a raga of the Carnatic style, in a festival named after the greatest of Hindu deities, held in the grounds of a school built in British times but named after a fort that dated to the 16th century and whose present form owed itself to both Hindu and Muslim rulers.

Notably, the year of the concert is also significant. For it was in 1956 that the Kannada-speaking regions of South India were brought together in a single political unit. When the British ruled India, Kannada speakers had lived in large numbers in the princely states of Mysore and Hyderabad, and in the Madras and Bombay Presidencies. After Independence, a popular movement for the unification of these territories had enabled the creation of a single consolidated state of Kannada speakers in 1956.

The celebrated Kannada writer, Kota Shivarama Karanth, once remarked that it was impossible to “to talk of ‘Indian culture’ as if it is a monolithic object”. In Karanth’s opinion, “Indian culture today is so varied as to be called ‘cultures’. The roots of this culture go back to ancient times: and it has developed through contact with many races and peoples. Hence, among its many ingredients, it is impossible to say surely what is native and what is alien, what is borrowed out of love and what has been imposed by force. If we view Indian culture thus, we realise that there is no place for chauvinism.”

To this quote from Karanth let me append one by Rabindranath Tagore. Speaking of our inherited and shared diversity, Tagore once remarked: “No one knows at whose call so many streams of men flowed in restless tides from places unknown and were lost in one sea: here Aryan and non-Aryan, Dravidian, Chinese, the bands of Saka and the Hunas and Pathan and Mogul, have become combined in one body.”

The pluralism and cultural heterogeneity that Karanth and Tagore highlighted mark most spheres of Indian life. And perhaps (as they knew so well themselves) our classical music above all. Whether it be instrument or raga or genre or performer, we cannot say what is Hindu and what is Muslim, which part is native and which alien. Now, I do not know if our prime minister is a fan of shastriya sangeet. Even if he is not, I would urge him, and every other supporter of Hindutva, to spend half-an-hour on YouTube listening to the composition I have profiled in this column. They then might reconsider their narrow-minded, dogmatic, understanding of India, of what it means to be an Indian. For the act of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan singing Hamsadhvani at a Rama Navami concert in Bangalore’s Fort High School in 1956 brings and blends together many languages, religions, regions, political regimes, musical traditions, and architectural styles. It is a glorious tribute to the cultural diversity of our country and our civilization. And incidentally a gorgeous piece of music too.

(Ramachandra Guha is an Indian historian and writer.)