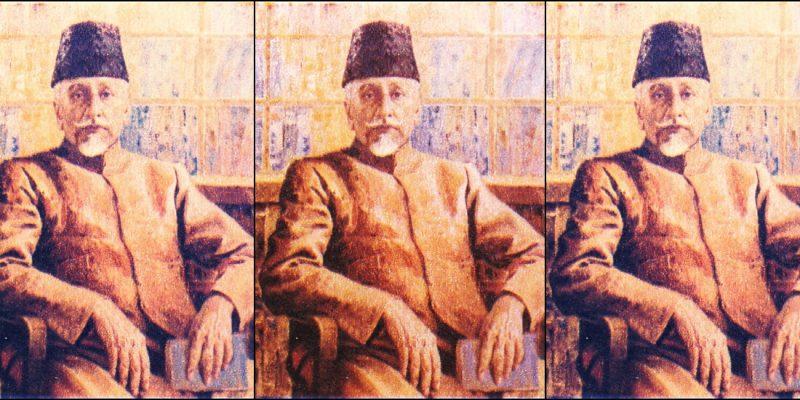

Maulana Azad was never as relevant for us as he is now. It is unfortunate that he has been pushed the margins of the history of India’s freedom struggle. Not much is known about him, though he was one of the four or five top leaders of the Congress party.

He is important for us today because he left behind an intellectual and political legacy that is under severe strain. Azad spent most of his life propagating and defending an idea of India that was premised on a composite/indivisible nationalism. He also articulated his faith afresh, rejecting the theological inheritance that he got from his puritan father. I see his relevance today because both his concerns mentioned above are under threat.

Azad began his early career as a scholar and also as a journalist when he was barely 15. Most of his engagements in this phase were limited to Islamic theological as well as communitarian concerns. Soon his anti-imperialist battle began as the editor of Al-Hilal, his newspaper that was launched in 1912 from Calcutta. Maulana Azad was declared the most dangerous Indian by the colonial administration for his ‘seditious’ writings even before he joined the Congress and the freedom struggle formally.

He committed himself to integrative politics, leaving aside purely narrow Islamic concerns. He battled for an indivisible nationalism where religious identity had no divisive role. This is for his detractors today, who themselves kept aloof from this intense battle till the end and do not feel ashamed in casting communal and other baseless aspersions on Azad. Let us touch upon some of the key questions related to the above mentioned two issues.

I have tried to explore Azad’s engagement with Islam and his interpretation of Quran in my recent book extensively. Hewas exposed to a puritan Islam through his father Maulana Khairuddin, who was himself an Islamic scholar and a Sufi. Despite the fact that Azad stayed a firm believer, except for a short youthful phase of unbelief if not atheism, which Azad confesses as part of his human frailties. In reading Azad, we enter into the world of Islam just as we enter into the world of Hinduism when we read Vivekananda. It is imperative to refer to Swami Vivekananda today, as he is touted as a great proponent of Hindutva and its politics. Vivekananda spoke of compassionate Hinduism and his discomfort with religious hatred and violence in his iconic address to the Chicago Assembly in 1893 when he said:

“Sectarianism, bigotry, and it’s horrible descendant, fanaticism, have long possessed this beautiful earth. They have filled the earth with violence, drenched it often and often with human blood, destroyed civilisation and sent whole nations to despair. Had it not been for these horrible demons, human society would be far more advanced than it is now. But their time is come; and I fervently hope that the bell that tolled this morning in honor of this convention may be the death-knell of all fanaticism, of all persecutions with the sword or with the pen, and of all uncharitable feelings between persons wending their way to the same goal.”

Vivekananda did not allude to any particular religion but raised a larger issue involving all religions and faiths of the world. He spoke against intolerance and violence which diverse faiths have indulged in against each other over the years. Azad is not very far from Vivekananda in his understanding of religions, when he writes in Al-Hilal as a young scholar and later elaborates his view of Islam and other faiths in his Tarjuman al Quran. Azad concluded that:

“All the religions of the world are correct, but their followers have deviated from the truth. All ignorance, opposition, differences of claims and conflicts of organisations, which we now find, are due to lack of intelligence and defective actions of the followers of religions; in the teachings of religions there is no difference whatsoever.”

As I mentioned before, Azad’s phase of unbelief did end and a somewhat refurbished faith came back but skepticism never left him, he always stressed on the critical faculties, which god gifted to humans to make them ashraful makhluqat (the best of god’s creations). He was even closer to Vivekananda when he said soon after independence that for “the advancement of nations there is no greater hindrance than narrow-mindedness…In the domain of religion it appears in the form of blind faith and wants to deceive us in the name of orthodoxy.” His Tarjuman al Quran was an interpretation of faith with a comparative religion perspective and not an attempt to see Islam as a supremacist religion. Azad said:

“If humanity is to be brought together it will only be on the basis of mutual understanding, especially in matters of fundamental belief. The philosophical understanding of the nature of ultimate reality, and the practice of love, regardless of the distinction of creed, community, and nationality, these are the basic teachings of the Quran.”

This was the spirit of the faith he practiced and preached all his life. It inspired his politics and his definition of identity and nationalism as well. It was humanism that remained supreme, taking precedence over religious or national identity.

We find that the same eclectic spirit and humanism permeated his articulation and understanding of nationalism too. He spent all his life battling for a united India based on composite nationalism. The notion of composite nationalism, which Azad espoused, can be traced back to the early history of Islam. He used the oft cited example of the Prophet of Islam who formed the first nation of the early believers in Madina. The prophet signed a covenant to form a United Front, which included the Quraish, the Ansars and the Jews, and brought them together as one nation against their common enemy.

Azad stressed on the usage of the word qaum for the Hindus and Muslims to form a one nation, following the example of the Prophet. This was the strongest argument he put forth before Indians, particularly before the Muslims, that a composite nationalism is possible. Azad urged people to keep away from the Muslim and Hindu communalists who were pushing for a divisive idea.

Azad engages with the idea of patriotism and nationalism in one of his articles, ‘Islam and Nationalism’, in Al-Hilal in 1927. Here, his engagement culminates into a maturity which he calls the stage of ‘humanism’ and ‘universalism’. At this stage, Azad says, man realises that the boundaries and relative affiliations of human associations and areas that he had created were not actual and natural. In the words of Azad, “True relationship is only one, the entire earth is man’s native land, mankind one family, and all human beings are brothers. At this stage the voyage of man’s collective affiliations terminates, and, in place of unity of race, unity of place, and unity of nationality, the only and perfect unity, the unity of the human race…manifests itself.”

In the context of both religious faith as well as the idea of nation and nationalism, Azad’s stress on humanity is starkly lacking in our societal as well as political lives. It is this human element and the idea of togetherness that needs to be resuscitated if we want to remain a forward-looking nation.

(S. Irfan Habib is a historian and author of a recently published biography, Maulana Azad: A Life. Courtesy: The Wire.)