(An extract from: Katherine Connelly, Elaine Graham-Leigh, Feyzi Ismail and Lindsey German, “Marxism and Women’s Liberation”, Counterfire 2016.)

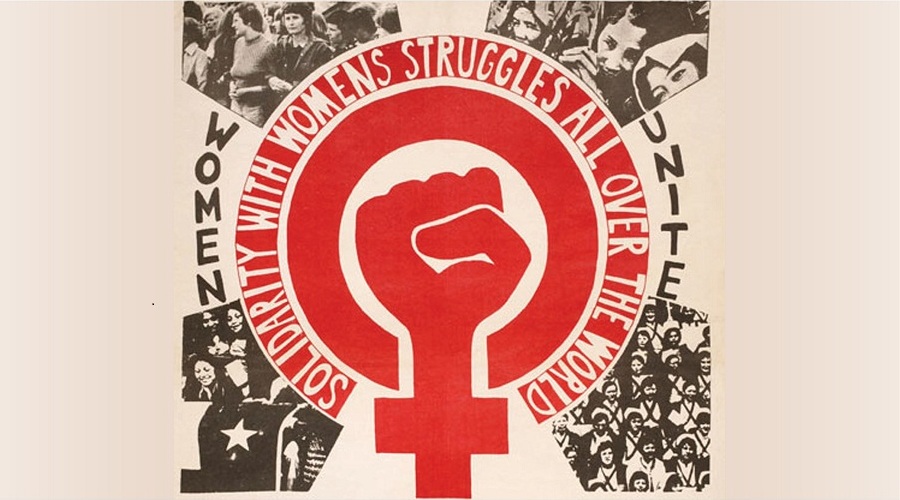

Marxism and feminism have had a relationship which has been described famously as an ‘unhappy marriage’. While those who were attracted to the feminist ideas of the 1960s and early 1970s often had a close relationship to Marxism, the experience of the last few decades has been that the two have led largely separate lives. The various Marxist analyses of oppression and the various feminist ones tended to develop along different paths.

However, while there was been an acceptance of mainstream feminism at many institutional levels within capitalist society, it has also become increasingly obvious that the position of women is not improving overall. Indeed, in a globalised, neoliberal world, women are facing levels of exploitation and oppression which are both interlinked and heightened by the nature of that society. The need for migration, precarity, insecurity and intensification of work, all impact heavily on women.

This in turn has led to an increased interest in feminism, and in the need to explain and understand the nature of women’s oppression, as new generations of feminists search for analysis which links women’s equality to a wider critique of capitalist society. In a world where women’s oppression remains a central feature of society, the need for an analysis which locates the fight against oppression in the context of a fight against class society is more and more pressing. In such a context, Marxism has an important contribution to make in terms of analysing oppression and its links with exploitation.

Marxism’s recognition of oppression

Marxism is a theory of human emancipation, sometimes called a universal theory, which attempts to explain all oppression and exploitation in relation to class society. This has often led to the charge from some feminists that it is a ‘reductionist’ theory – that it reduces all such questions to ones of class, rather than considering the specific nature of women’s oppression. A second feminist criticism, and in some way connected to this, is that Marxism denies the agency of individual men as the perpetrators of oppression, because it sees oppression as created by class. It therefore denies the need to organise against men as well as against capitalism.

Both involve a misunderstanding of what Marxist class analysis is about. It starts from the understanding that capitalist society is divided into classes, but this is not necessarily a straightforward division. Marx sees class as an economic relationship, defined by individuals’ relationship to the means of production. There are two main contending classes, who on the one hand exploit and on the other hand are exploited. This in itself might be a fairly straightforward picture, with the main classes being either the working class or the ruling class. But there are both divisions within the working class, and also a number of other, smaller groups or classes who have some relationship to one or the other of the main classes.

Marxist theory is centred on an economic theory of exploitation, in which the surplus produced through work is expropriated by those who control the production of wealth and its distribution. Yet it is not simply an economic theory. It also aims to explain political and social divisions in terms of the needs of an exploitative system, the way in which divisions within society are created and recreated to suit the needs of this system, and the extent to which ideas and actions themselves develop as a result of the economic relationships in society.

While the working class is the exploited class, it is not a uniform class. It has divisions in terms of gender, race, sexuality, nationality, skill, and many others. These divisions also often cut across classes: all women suffer a specific oppression as women; all black people suffer a specific oppression because of their race.

The recognition of that oppression is crucial for Marxists and socialists, and the recognition that it needs to be specifically located and fought against as part of a wider struggle to change an exploitative and oppressive system is also key. The strength and enduring power of the great movements of the 1960s are precisely that they did this. In so doing, they created a situation where the working-class movement had to take on board the understanding of oppression and the need to overcome it even within the working class.

However, those of us who locate oppression within class society also argue that it is only in the process of fighting to overcome class society that the movement to end oppression can really succeed. Only when class relations of production, which help create and recreate oppressions precisely in order to divide those who are exploited, are overthrown, can full equality and freedom from all divisions really be achieved.

This analysis allows us to integrate the struggles against oppression into the wider fight against class society. Far from reducing oppression to class, this broadens out not just the analysis of oppression but points to ways of fighting against it. Developing a class analysis of oppression which goes beyond locating that oppression but also views that oppression through an understanding of its link to class society and the necessity to overthrow it, enables Marxism to have a much more extensive view of oppression and class.

Connecting Marxism and feminism

The points made by thinkers in the Marxist tradition, that the nature of capitalist society prevented genuine equality for women or any other oppressed group precisely because capitalist production ensures the continuation of privatised reproduction, remain true. This is despite the very real gains which have been made for women under capitalism. And even these gains can find themselves under attack, whether in terms of wages and conditions at work, or over issues such as abortion and reproductive rights. We have seen, for example, the recent attempt by the Polish government to limit even further abortion in that country, which was met by a women’s strike (supported by many men) that successfully defeated the move.

The need to go beyond capitalist society to achieve women’s liberation does not mean ignoring current attacks, or counterposing a long-term glowing egalitarian future with the harsh reality of the present. It means that the fight for women’s liberation has to be both about defending and extending existing gains, while always arguing that permanent liberation for not only women but the whole of humanity is only possible in a society based on production for need, not profit.

This directly connects to a critique of different sorts of feminism, and it leads to an understanding of why there is such a schism between those who see feminism simply in terms of individual women’s advancement and those who see it as connected to wider social change. Capital in the age of neoliberalism is happy to accept a small number of women making it to the top, as long as they are committed to maintaining the status quo. So while there is the prospect of the first woman US president this year, she is no friend of working women. She accepts the inequality agenda of Wall Street, is an inveterate warmonger and is determined to enforce worse conditions on millions of workers, including women. The British prime minister, Theresa May, espouses conservative social values and promotes policies which attack workers’ rights.

Feminism and women’s liberation are not about individual empowerment, feminist consumerism (the right sort of T shirt), or getting individual women into ‘top’ positions. They are not primarily about getting women’s images on banknotes, or adopting ‘role models’ whose success is usually based on the employment of other women to carry out their domestic labour and childcare. They are about linking the question of women’s oppression to other inequalities and oppressions: racism, imperialism and the consequences of working-class exploitation.

It is here that the connection between Marxism and feminism can be made. The fight against capital takes many forms, including the fight for women’s full equality. Increasing numbers of people are recognising that different issues and campaigns are connected, that there needs to be a system change in order to deal with the inequalities and wrongs which afflict the vast majority of us. To achieve this will take a movement based on class, but one which is informed and fully participated in by the movements against oppression. The possibility of achieving this may appear daunting, but it is also more necessary than ever if we are to achieve equality.

(As national convenor of the Stop the War Coalition, Lindsey was a key organiser of the largest demonstration, and one of the largest mass movements, in British history. Article courtesy: Counterfire, a UK socialist organisation and website.)