The fighting peoples of the world lost a humble legend yesterday. Diego Armando Maradona was 60-years-old. Arguably the greatest soccer player to ever grace the pitches, the spirited striker combined unparalleled skills in his sport and an unflinching outspokenness before oppression. No other sports figure’s public statements and transformation has equally captured the changing momentum across Latin America.

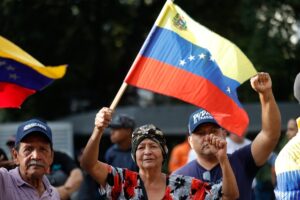

The hundreds of thousands of tributes being paid throughout the world portray a particular image: Maradona in close solidarity with the biggest progressive leaders of the social reformist wave embraced by the peoples of Latin America, the so called Pink Tide. In fact, Maradona put to the service of the Bolivarian revolution in Latin America all his fame, his influence and his skilled legs. He embraced the peoples of Cuba, Venezuela, Brazil, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Argentina and more, by developing deep friendships with Fidel, Raúl, Lula, Evo, Hugo, Nicolás, Daniel, the Kirchners, and many more.

Maradona was for the people of South America what Mohamed Ali was for Black America.

The Falklands War

Born in the oppressed community of Villa Fiorito in the outskirts of Buenos Aires, “the golden kid’s” (pibe de oro) talent from an early age fetched him million dollar contracts first in his homeland and then in Barcelona and Napoli. No stranger to controversy, “the soccer god,” with his rebellious natural hair, was irreverent before elites and defiant to the core. When a Spanish player hurled racist epithets at him because of his indigenous ancestry, Maradona headbutted him leading to a brawl that was broadcast before King Juan Carlos, in front of a hundred thousand fans in the stadium and with half of Spain watching on television.

Maradona, who was 22-year-old years old at the time, was radicalized by England’s 1982 Falklands War assault on his homeland, known in Latin America as “la guerra de las Malvinas” and “la guerra del Atlántico Sur”. Causing untold agony and trauma, hundreds of soldiers died on both sides and hundreds of veterans committed suicide for years after. Reagan’s US claimed to be a “mediator” but stayed faithful to their junior colonial partner led by the ultra-conservative Margaret Thatcher.

This was the backdrop of the 1986 semi final showdown between the two countries, without diplomatic relations, at the World Cup in Mexico City. Argentina was South America and South America was Argentina.

During this fateful match, Maradona famously scored a crafty goal where slow motion highlights show he illegally used his hand to redirect the ball into the English net. When the English team accused him after the game at the press conference of cheating by using his hand, he responded that “sería la mano de dios,” “it must have been the hand of god.” Sports analysts applauded the “picardía” or Argentine cunningness behind the maneuver. The second goal was a miracle of human athletic skill. Maradona made a full sprint, starting on the Argentinian side, far from the English goalkeeper, and clearing a path through a minefield of English defenders, to execute a stunning goal that went down in sports history as “the goal of the century.”

These heroic acts sealed Diego’s destiny as an idol of the masses combatting neo-colonialism.

To beat England in Latin America was to exact revenge on the invading enemy. The soccer field was an extension of the battlefield; the arrogant English were expelled. This was the symbolic recuperation of Argentine and South American dignity.

The homeland is humanity

Jose Marti wrote that “our homeland is humanity.” The relationship Maradona established with Cuba was the full expression of the Cuban poet’s words.

In 2000, an overweight and beleaguered Maradona travelled to Cuba to treat his drug addiction. Fidel Castro visited him in his worst moments and helped take care of him. The Cuban president took off his military coat and gave it to the patient. Maradona said he adored Fidel because he was “genuine and cared about human problems that others brushed aside.” The down-and-out “wretched of the earth” was not rejected in Havana; he was accepted, treated like a dignified human being and loved. This moment of healing was another of Maradona’s entry points into the tide of resistance that was flowing across the Americas.

The same year, Japan denied Maradona a visa because of strict laws barring anybody from the country who had a history with drugs. Today, however, past and present Japanese soccer players pay tribute to Maradona.

The Frontlines in the Battle of Ideas

The Argentinian took great pride in the rising of Latin America’s second independence which began on December 6th, 1998 with Hugo Chávez’s electoral victory in Venezuela.

In 2005, the Frente Amplio’s Tabaré Vázquez received George Bush in Uruguay in a move that was considered a betrayal by his party and the region. Bush was promoting the FTAA, the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas. “Free trade” to Maradona and millions of Latin Americans is the freedom of the U.S. and transnational capital to expand its tentacles across more of the continent.

The Bolivarian Revolution was advancing across Latin America and had recently paid off Argentina’s foreign debt. Hugo Chávez traveled to Argentina to contest the interventionist and free trade agenda of the U.S. leader. La Plata river divided the two countries and the two sides of history. Rising to the historical occasion, with Diego by his side donning a “Stop Bush” t-shirt, the Venezuelan leader famously chanted: “El que no brinca es yankee” (If you don’t jump you’re an imperialist.) Maradona gave credence to Evo Morales’ catch phrase: “the empire stands with the right wing, football stands with the left.”

This was the battle of ideas Castro spoke of.

A strong backer of the Pink Tide

It is perhaps difficult to appreciate Maradona’s greatness in a country whose sports loyalties are divided between baseball, North American football and basketball. In South America and Europe, soccer is king. In Napoli, restaurants have alcoves reserved for hanging religious idols. There beside them is Maradona. The mayor has announced the famed Saint Paul stadium should be renamed after one of the city’s most beloved.

The mainstream press is also remembering the football titan but consciously shying away from his political commitments. Other outlets are accusing Maradona of being anti-American. Like the political leadership he so admired, Maradona never expressed ire towards the people of the United States but rather towards its political leadership who thought they were “the county sheriff.”

Through the years of the Pink Tide, Maradona was a regular on television programs and at rallies with Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Daniel Ortega, José “Pepe” Mujica and other anti-imperialist figures of the continent. His tattoos of Ernesto Che Guevara and Fidel Castro brought a new meaning to the phrase “he wore his feelings on his sleeve.” His program “De Zurda” on TeleSUR in 2014 with Víctor Hugo Morales, the famed Uruguayan sportscaster, combined humor, sports analysis and leftest political commentary. Last year, following a coaching win in April, he stated: “I want to dedicate this victory to Nicolás Maduro and all Venezuelans, who are suffering. These Yankees, the sheriffs of the world, think just because they have the world’s biggest bomb they can push us around. But no, not us.”

Those who had the honor to meet Dieguito remember him as a people’s person who was always accessible. Though he had his own personal struggles, he never wavered in his commitments to elevating the voices of the poor and defending the underdog. Yesterday, on the fourth anniversary of Fidel Castro’s passing, one of his students and admirers joined him in eternity, having left so much for us all to savor and learn from.

(Danny Shaw is Senior Research Fellow at COHA. William Camacaro is COHA’s Senior Analyst.)

❈ ❈ ❈

In another obituary, “Diego Maradona: Comrade of the Global South”, Dave Zirin writes:

The world mourns today the passing of Diego Maradona, the soccer god and revolutionary from Argentina whose play inspired all manner of poetry and prose. The best description of Maradona’s abilities came from the late Eduardo Galeano, who wrote of Maradona in his book Soccer in Sun and Shadow,

“No one can predict the devilish tricks this inventor of surprises will dream up for the simple joy of throwing the computers off track, tricks he never repeats. He’s not quick, more like a short-legged bull, but he carries the ball sewn to his foot and he’s got eyes all over his body. His acrobatics light up the field…. In the frigid soccer of the end of the century, which detests defeat and forbids all fun, that man was one of the few who proved that fantasy can be efficient.”

That Maradona died of a heart attack at the too young age of 60 seems preordained for multiple reasons. He lived a life of excess and addiction; of cocaine and massive weight fluctuations that undoubtedly placed a mammoth stress on his heart. He also lived a life of passionate, rebel intensity, always standing against imperialism; always standing for self-determination for Latin America and the Global South, always speaking for the children growing up in conditions similar to the abject poverty of his own upbringing in the Villa Fiorito barrio of Buenos Aires. He was the fifth of eight children, living without running water or electricity, and never forgot it for a moment. His heart may have simply been too big for his chest.

Maradona took political stances throughout his life that were never easy. A Catholic, he met with Pope John Paul II and told the press afterward, “I was in the Vatican and I saw all these golden ceilings and afterwards I heard the Pope say the Church was worried about the welfare of poor kids. Sell your ceiling then, amigo, do something!”

He tried to form a union of professional soccer players for years, saying in 1995, “The idea of the association came to me as a way of showing my solidarity with the many players who need the help of those who are more famous.… We don’t intend to fight anyone unless they want a fight.”

Maradona always stood with the oppressed, particularly with the people of Palestine. He made sure they were not forgotten, saying in 2018, “In my heart, I’m Palestinian.” He was a critic of Israeli violence against Gaza, and it was even rumored that he would coach the Palestinian national team during the 2015 AFC Asian Cup….

Many will surely write about Maradona’s prowess on the pitch; his legendary World Cup runs, his “hand of God” goal against England, his ability to go the length of the field with the ball “sewn to his foot.” Others will dwell over his torments, his pain, and his demons. But let’s take a moment and raise a glass to Diego Maradona, comrade, friend, and fierce advocate for all trying to eke out survival in a world defined by savage inequalities. Many are writing today that Maradona is now resting in the “hand of God.” I prefer to believe that he is hard at work organizing the angels. Diego Maradona: ¡Presente!

(Dave Zirin is the sports editor of The Nation.)