❈ ❈ ❈

The End of an Era of Indian Environmentalism

Hridayesh Joshi

Kya hain jangal ke upkaar

Mitti paani aur bayaar

Mitti paani aur bayaar

Zinda Rahne ke Aadhar

(What are the blessings of forests on us.

They provide us healthy soil, clean water and air

which make life possible for us.)

This legendary slogan that has echoed in the Himalayan valleys since the 1970s and galvanised an entire generation, was coined by Sunderlal Bahuguna, leader of the famous Chipko forest conservation movement, that had men and women of Uttarakhand villages hug trees to protect them from the axe.

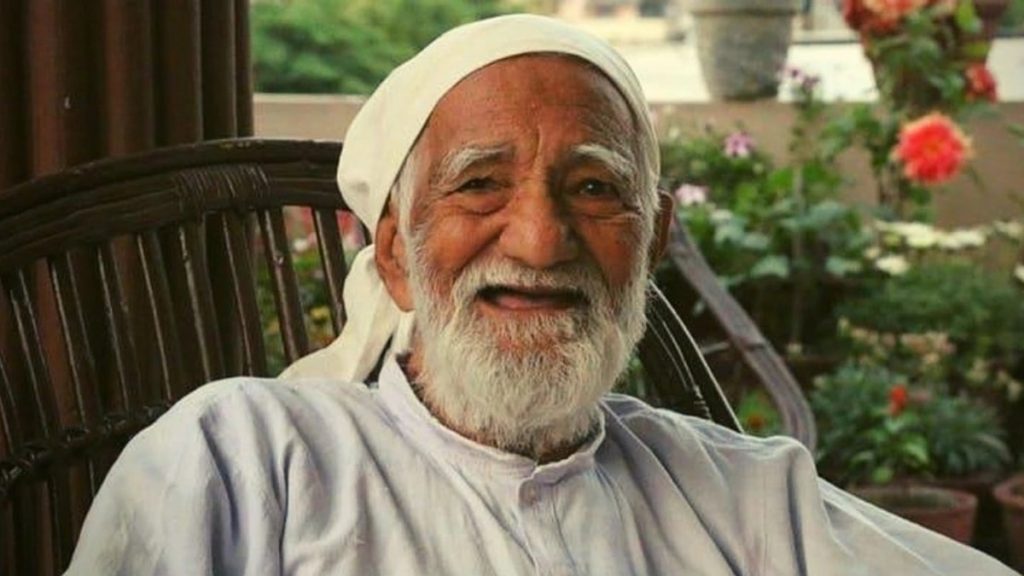

The 94-year-old environmentalist succumbed to COVID-19 on May 21, 2021, at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in Rishikesh, Uttarakhand. With his demise, India has lost one of the finest environmentalists and social workers who had also been part of India’s freedom movement.

Sunderlal Bahuguna was born on January 9, 1927, in Maruda village in the Tehri district, a hilly region of Uttarakhand, while India’s freedom struggle was in full swing. It was a time when people of his region were unhappy with the oppressive rule of the king of Tehri and had rebelled against him. On May 30, 1930, the king ordered the soldiers to open fire on unarmed protestors. Many died and their bodies were thrown in the river.

Bahuguna was then just three years old. Ten years later, he commenced his public life by participating in the rebellion against the same principality of Tehri. He went to Lahore for his B.A. (Bachelors of Arts) and then to Varanasi for his post-graduation degree. He, however, stopped studies to join the freedom struggle during which he was jailed as well. It was the start of his journey of public movements.

“Most of the people know Bahuguna for Chipko (movement) which came much later in the 1970s. By then Sunderlal ji had at least 25 years of social work and activism under his belt as his struggle commenced at a very young age. Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi, he fought against untouchability and to do so in true spirit he lived with Dalits (formerly untouchables) in the same house and ate with them,” journalist and writer Harsh Dobhal, who covered Bahuguna’s and his struggle closely for many years, told Mongabay-India.

Chipko, a forest conservation movement against tree felling, started in Chamoli district in the 1970s, where people led by women hugged trees to stop contractors from cutting them.

Dobhal said Bahuguna also worked for women’s education. “This was all in his youth. He was also part of the anti-liquor movement in the 1960s and of course, you can’t forget the sarvodayi movement he actively participated in,” Sarvodayi movement is rooted in Gandhian philosophy of upliftment of all.

A vow to work for the powerless

One of the finest accounts of Bahuguna’s life is written by renowned geologist Kharak Singh Valdiya. Valdiya declares Bahuguna Mahatma Gandhi’s soldier in Himayala and named the biography – Himalaya main Mahatma Gandhi ke Sipahi, Sunderlal Bahuguna.

Early in his life, Sunderlal Bahuguna met Gandhian Sridev Suman, who later died while on a long fast of 84 days against the atrocities of Tehri’s king, and that made a deep impression on Bahuguna. It moulded his political and social understanding. He vowed to work for the weak and powerless in a non-violent manner and practised what he preached.

“I do not eat rice as the crop of paddy consumes too much water which is bad for the environment. I do not know how much my abstention will help the cause but I want to live with nature in harmony,” he once said to this reporter during an interview.

“When he built an ashram in our ancestral village Silyara, he employed just one mason for construction. He toiled as labour during the building of the ashram and did all the work like carrying the stone, wood and building material himself,” Rajiv Nayan Bahuguna, son of Sunderlal Bahuguna told Mongabay-India.

The activist was also deeply impressed by another Gandhian Vinoba Bhave, who spearheaded Bhoodan Andolan (land gift movement) in the 1950s. While working with social activist Sarala Bahen, Sunderlal met Vimla Nautiyal, who was a committed social worker. Vimla Nautiyal’s brother Vidya Sagar Nautiyal was a prominent communist leader. Both Vimala and Sunderlal decided to marry.

It was his wife’s inspiration and insistence that Bahuguna quit parliamentary politics – he was district president of congress party – and devoted all his life to social work. The couple founded Parvtiya Navjivan Mandal and worked for the education of dalits and the poor. Throughout his life, he maintained that he couldn’t have done what he did in his life unless his wife had supported him.

Chipko and Tehri movements

Chipko movement was a result of many van andolans (protests related to forests and rights of people) going on in the Himalayan region for decades. In the Kumaon region of Uttarakhand, socialists were leading such movements and in Garhwal, it was mainly led by the Communists. Chipko movement threw many stalwarts like Govind Singh Rawat, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Vipin Tripathi, Vidya Sagar Nautiyal and Govind Singh Negi.

“Even before Chipko, since independence, there was a streak of van andolans going on in the Himalayas. Chipko can be termed as a culmination of them. Sunderlal’s role was pivotal as he organised and popularised the movement giving it a human face. He amplified the stark facts and adopted a pragmatic approach. This strategy forced the government to listen to the people,” writer and activist Charu Tiwari told Mongabay-India.

Bahuguna believed in a cohesive and coordinated conservation policy for the entire Himalayan belt. It was this belief of his that he did 5,000-kilometre-long foot-march between 1981-83 from Srinagar in Jammu and Kashmir in northern India to Kohima in Nagaland in eastern India.

After the success of the Chipko movement of the 1970s. Bahuguna gained national and international prominence. In the early 1990s, he reorganised the ‘Save Himalaya’ movement and launched his agitation against the Tehri dam. The first opposition against Tehri though was led by advocate and geologist Virendra Dutt Saklani, who took the matter to the Supreme Court of India in the 1960s. Later in the mid-1980s when Saklani got old and sick, he himself handed over the responsibility to Bahuguna.

He was firmly against constructing large hydropower projects in the sensitive ecological Himalayas as it caused large-scale destruction and displaced too many people in the hills where land is very limited for housing and habitation. The anti-Tehri dam movement was vehemently supported by N.D. Jayal, a mountaineer and bureaucrat who pushed the cause in New Delhi.

“What I found most powerful trait of Sunderlal ji is that while arguing for environmental conservation he would brilliantly combine hard science and his ground understanding. His voice was soft and gentle but very firm. This made him a great communicator. One more important thing about him was that he not only inspired people but also learned from common masses particularly from the women who have been at the forefront of all public movements in Uttarakhand,” said Ashish Kothari, who is associated with Kalpavriksh and Vikalp Sangam, non-governmental organisations working on environmental issues.

Bahuguna stationed himself at the banks of River Bhagirathi to oppose the Tehri project. The 45-days long fast he undertook in 1995 ended after the intervention of the then prime minister P.V. Narsimha Rao. In 2001, he again sat on a long fast of 74 days at Rajghat, New Delhi. Bahuguna could not stop Tehri dam but the struggle was not completely in vain.

“We have seen how big companies and governments taking away the land of the poor with no or meagre compensation. Though Bahugauna could not stop the Tehri Dam the questions he raised exposed the inhuman face of such so-called development projects. Even people sitting in power recognised this fact and a fair compensation was agreed upon. This was a great achievement,” Indian National Congress leader and activist Kishore Upadhyay told Mongabay-India.

Building new leadership

During his over 50-year-long active public life, Sunderlal Bahuguna inspired and groomed many others who dedicated themselves to the social and environmental cause. Pioneering environment journalist and editor Bittu Sahgal and singer Rahul Ram have told Mongabay-India about the impact of Sunderlal Bahuguna in their formative years.

Poet Ghanshyam Sailani, journalist Kunwar Prasun, dalit activist Bhawani bhai and Dhoom Singh Negi were deeply inspired by him. Pandurang Hegde started the Appiko movement in the lines of Chipko to save forest in Uttar Kannada district in Western Ghats of Karnataka.

In the Himalayas, Vijay Jardhari has led work to conserve hundreds of varieties of seeds like paddy, kidney beans and several native coarse grains. He said his Beej Bacho Andolan (save seed movement), which is an effort to save biodiversity and native species, is an extension of the Chipko movement.

“I must admit that the philosophy behind my work is Chipko which was led by Bahuguna ji. If we had not participated in Chipko with him, the Beej Bacho movement would not have never born. How would we have understood the importance of soil, water and environment? After the (Chipko) movement’s success whenever we went to villages, people would tell us how the variety and species of native crops are diminishing. We then understood that the use of toxic chemicals and fertilisers is ruining agriculture and biodiversity. Then we started this movement to protect desi (native) seed,” Jardhari told Mongabay-India.

(Courtesy: Mongabay India.)

❈ ❈ ❈

The Best Homage to Sunderlal Bahuguna Is to Strengthen People-Centered Protection of Environment and Forests

Bharat Dogra

Sunderlal Bahuguna is no more.

The veteran environmentalist and chipko movement leader passed away today (May 21) around noon at a hospital in Rishikesh, where he had been admitted about 2 weeks ago following Covid-type symptoms.

Born in a village along the bank of the Ganges river in Tehri Garhwal (presently a district of Uttarakhand), as a schoolboy he met Sridev Suman, the famous freedom fighter who later sacrificed his life during a jail sentence, and decided to follow his example of a deeply committed social life. He started secretly sending out news relating to Suman and faced police action. He escaped to Lahore but returned when the freedom movement in the Tehri kingdom was beginning to peak. At first stopped from entering Tehri, he joined the struggle somehow and contributed much.

After independence he devoted himself to various social commitments. With his unquestioned honesty and deep commitments he was then the rising star in the social-political life of Garhwal. A marriage proposal from the father of Vimla emerged but his daughter had by then become a disciple of social activist Sarla Behn and was devoted to serve villagers outside the limelight of mainstream politics. She laid down this condition for marriage to Sunderlal that they will serve people together in a difficult rural region. Marriage followed and the couple settled down to serve villagers in Silyara, near Ghanshali, close to Balganga river. Both firmly accepted Mahatma Gandhi as their main teacher and inspiration.

Following the Chinese invasion leading Gandhian Vinoba Bhave called upon Gandhian social workers in the Himalayan region to play a wider social role and so now with the consent of Vimla, Sunderlal started travelling more widely in many parts of Uttarakhand, particularly the Garhwal part. This led to increasing involvement with social and environmental concerns. Both Sunderlal and Vimla were involved in anti-liquor movements and dalit assertion movements which challenged various forms of untouchability. Enduring relationships were established with several younger activists like those in Henvalghati region. Around the late seventies a series of Chipko movement activities centered in Henvalghati region were launched for saving forests like those of Advani and Salet which generated a lot of enthusiasm. The action shifted then to even more remote forests like those of Kaangar and Badiyargad, where Sunderlal Bahuguna went on a long fast in a dense forest area in very difficult conditions. Side by side he maintained a dialogue with senior persons in the government. The prime minister Mrs. Indira Gandhi in particular had very high respect for him. Very big success was achieved as the government agreed to stop the green felling of trees in a vast Himalayan area.

Following this success Sunderlal went on a very long and difficult march from Kashmir to Kohima, including Bhutan and Nepal, covering a vast part of the Himalayan region to spread the message of saving forests and environment with the involvement of people. During this march, taken up in several stages, several times he faced threat to life but did not stop and completed the march.

He emphasized protection of sustainable livelihoods along with protection of environment. He was involved closely in resisting displacement and organizing forest workers. He was also involved in several constructive activities relating to regeneration of degraded forests and promoting organic/natural/traditional farming.

Soon he was in the thick of the movement for avoiding the harmful social and environmental aspects of dam projects in Himalayan region particularly the gigantic and highly controversial Tehri dam project which was being promoted despite being extremely hazardous, as confirmed even by high-level official reports. This proved to be a very long and difficult struggle. Sunderlal Bahuguna left his ashram and camped on the bank of the Ganges river for several months, accompanied by Vimla.

Although this long struggle did not succeed in stopping the high-risk dam, but certainly it spread awareness of these important issues far and wide.

Sunderlal Bahuguna also emerged as an inspiration source for forest protection and environmental struggles in many parts of India and even abroad. In the Western Ghats region, for instance, he was an important inspiration source for the great Appiko movement for saving forests. He was invited to important international conferences and his opinion on environmental issues was widely sought. He was honoured with several prestigious awards, including the Padma Vibhushan.

All his life he worked as a part-time journalist and writer in Hindi and English languages to earn livelihood support. His articles and reports, not to mention interviews with him, have been published in many leading newspapers and journals .Vimla ji told me that she is very keen that at least two collections of his writings published over the years should be brought out.

He contributed to many constructive causes such as the Bhoodan (gift of land) movement and evolving an alternative development strategy for the Himlayan region rooted in a combination of combining environment protection with sustainable livelihoods.

He spent his last days in Dehradun at his daughter’s home. Last year when I wrote the biography of Sunderlal and Vimla Bahuguna and went to Dehradun with my wife Madhu to present the book to them, he was eager and happy to converse, despite being weak. He was being looked after with great care by Vimla, helped by their daughter Madhuri.

He leaves behind Vimla and three children, Madhuri and two sons Rajiv and Pradeep.

Our best homage to him will be to work for combining environment protection and sustainable livelihoods.

(Bharat Dogra had been close to Sunderlal Bahuguna over more than four decades. His recent books include Vimla and Sunderlal Bahuguna—Chipko Movement and the Struggle Against Tehri Dam Project.)