Ladakh at a Glance

Also known as “the land of Passes”, Ladakh is situated along the historic Silk Route, which had a great influence on the development of its history, trade, commerce, culture, and philosophy.

- Population (2011 Census): 2,74,000 (predominantly tribal)

- Languages spoken: Ladakhi, Balti, Purik, Tibetan, English

- Administration: The two districts of Leh and Kargil are administered by Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, Leh, and Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, Kargil.

- Kargil | Area: 14,036 sq km; Population: 1,40,802; Biggest ethnic group: Muslims

- Leh | Area: 45,110 sq km; Population: 1,33,487; Biggest ethnic group: Buddhists

●●●

At the Ladakh Buddhist Association’s (LBA) premises, a stone’s throw from Leh’s bustling main market, where hawkers entice foreigners with traditional crafts, there is a rush of people. Some of them are crammed on a bench, others kneel in the sand-fringed verandah with the sun beating down on them. They have stacks of paper on their laps and are filling a form hurriedly.

A man reveals the reason for the commotion: “We can’t wait to see the Dalai Lama.” The Tibetan spiritual leader is in Leh, and the LBA is registering people for a possible meet-up. Bright bunting with Buddhist sutras inscribed in the Tibetan script hang from the crossings and roofs of nearby houses. But the festive gaiety contrasts with the dour faces of some of the men and women assembled there.

Kunzang, a staff nurse at the Sonam Nurboo Memorial Hospital, says that much of Ladakh is on tenterhooks, fretting over the influx of “outsiders”, a possibility thrown open by its Union Territory status, which ended the Ladakhis’ exclusivity in land and jobs.

Four years ago, when Ladakh was cleaved from the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir, there were celebrations on the streets. At least for the Buddhist population in Leh, it was a triumphant moment in a decades-long struggle for a destiny independent of Kashmir.

“It [Kashmir] was the seat of power. It concentrated all power,” said Rigzin Jora, a former Minister in undivided Jammu and Kashmir, about the way generations of Ladakhis looked at Kashmir. He gravitates towards the word “superficial”, while describing the pre-2019 composition of Jammu and Kashmir, a mosaic of culturally distinct ethnicities, with different histories and different attitudes for the future.

Demand for UT status

Ladakh’s demand for Union Territory status gained prominence in 1989, the year Kashmir saw the eruption of a wave of insurgency. But unlike Kashmir, the Ladakhi struggle was not bloody: only four protesters have ever been killed in police firing. It culminated in the Autonomous Hill Development Councils, for Buddhist-majority Leh (in 1995) and Muslim-majority Kargil (in 2003), its two districts separated by decades of competing aspirations that had more than once flared up into economic blockades.

But sooner than one imagined, the people’s sense of jubilation was replaced with a strong argument for caution against New Delhi’s direct rule. Among other things, the administration of Lieutenant Governor B.D. Mishra, a New Delhi appointee, has attracted criticism. He has not filled vacancies in the public sector. Meanwhile, new jobs remain elusive with non-local people swallowing up the existing ones.

“Unemployment is a major concern,” said Kunzang. But what galls her more is the outsourcing of high-ranking employees from other States. “Visit a nationalised bank, a post office, or any other public enterprise, you will find Ladakhis working as peons, guards, and canteen staffers—they report to non-local managers and administrators,” she said with a frown.

Under the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019, Ladakh became a Union Territory without an elected legislature, headed by a Lieutenant Governor. People from anywhere in India can now acquire land and jobs there if they meet certain requirements.

When Article 370 (it accorded special status to Jammu and Kashmir) was abrogated, Kunzang was thrilled to see the BJP’s young parliamentarian from Ladakh, Jamyang Namgyal, chastise Kashmiri politicians in Parliament. “For seven decades these [Kashmiri] leaders did not accept us, sidestepped and called Ladakh a piece of land where no grass grows,” Namgyal, then 34, said on August 6, 2019, hailing Ladakh’s separation from Jammu and Kashmir. Kunzang has since realised that the BJP’s pledge of a great, reforming government was thin on substance.

Inside the LBA office, in a well-furnished boardroom filled with the aroma of tea, senior members are no less exasperated than Kunzang. They list everything that is wrong with Ladakh’s state of affairs: an administration run by a handful of bureaucrats who have walled themselves off from contrarian viewpoints; an impending threat to demography; and stiffening competition in businesses and jobs, which the “skilled outsider” is likely to exploit. “Ladakh has changed a lot, but not for the better,” said Chering Dorjay, LBA vice president.

The LBA is part of the Leh Apex Body, a collective of several trade unions and religious and political groups pressing for greater autonomy. The Apex Body has joined hands with its Kargil counterpart, the Kargil Democratic Alliance (KDA), as the two districts exhibit signs of determination to forget past divisions and repair the fault lines.

This will destroy the attempts of successive governments in the erstwhile State to fragment regional leaderships. A Kashmiri journalist working with a foreign publication said that “it was the Congress which architected societal fissures, pitting Buddhists of Leh against Muslims of Kargil and Kashmir. The BJP milked it.”

The BJP’s meteoric rise is often attributed to the personal clout of Thupstan Chhewang, nephew of Kushok Bakula Rinpoche, the architect of modern Ladakh. Convinced that the BJP would fulfill the people’s aspiration for Union Territory status, Chhewang joined the party and won it the Ladakh Lok Sabha seat in 2014. He parted ways with the BJP in 2018 and now heads the LBA. But the BJP, riding on a “Modi wave”, retained the Ladakh seat in the 2019 parliamentary election. Its fortunes are now diminishing. In the Leh Hill Council’s byelection in the Temisgam segment in September 2022, it lost to the Congress.

Charter of demands

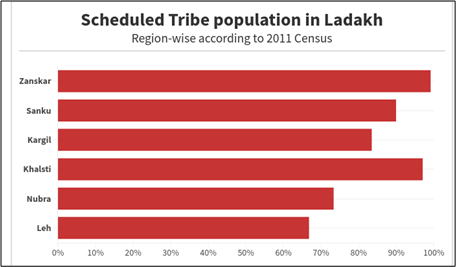

The Apex Body and the KDA’s charter of demands includes safeguards under the Sixth Schedule, statehood for Ladakh, increasing the number of Lok Sabha seats from one to two, besides representation in the Rajya Sabha. Ladakh, in the absence of an elected legislature, currently does not send any member to the Upper House of Parliament. The two organisations have spearheaded a series of protests and shutdowns in Leh and Kargil. The Sixth Schedule is a constitutional provision safeguarding tribal culture. In Ladakh, 90 per cent of the population is tribal.

In January, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) constituted a high-powered committee to “ensure the protection of land and employment” for the people of Ladakh. But the KDA and the Apex Body refused to engage with it sensing dilution of their core demands. Months of browbeating ended in June when the two bodies sent six delegates to New Delhi to meet Nityanand Rai, the Minister of State in the MHA.

Dorjay said he expected Home Minister Amit Shah to invite the Apex Body and the KDA for a fresh round of talks. According to him, the wave of discontent against the government is swelling, as the bureaucrats—whom many in Ladakh deride as “aloof elites from Delhi”—have become “too powerful” and are loath to consult civil society or even the elected hill councillors, generating a ruler versus ruled perception among Ladakhis.

The Congress party’s Tsering Namgyal, who is also the Leader of the Opposition in the Leh Hill Council, where the BJP currently has a majority, gives an insight into the systematic erosion of the councillors’ authority. “On important matters of public interest, the councillors are not taken on board, even as key assets such as the State land rests with the council. The outcome is a bureaucrat-controlled power apparatus that is neither consultative nor accountable to the people,” Namgyal said.

Shafi Lassu, advocate and human rights defender, agrees. Concentration of power, he said, had led to bad governance. “The SSC [Staff Selection Commission] exams were held in 2021, but there is no headway,” he pointed out.

While even the BJP’s critics agree that there has been remarkable progress in infrastructure, with excellent four-lane all-weather roads coming up in the past few years, their benefits might not be meant for Ladakhis.

Smanla Dorje, a young councillor from Saspol, vented his exasperation over non-local people monopolising projects for infrastructure building. He said only small contracts involving a few crore rupees were subcontracted to Ladakhis, while builders from other provinces got the big ones.

The influx of non-local entrepreneurs has also scuppered other small businesses. Take the case of Aijaz Bardi. Ten years ago, he procured an MSME (Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises) loan of Rs.10 lakh from the Jammu and Kashmir Bank and floated A.A. Enterprises. “It was a sale and service venture that picked up swiftly, bringing me a net profit of Rs.60,000-70,000 every month, after deducting loan EMIs,” Bardi said. His company supplied computer hardware and other electronic gadgets to the Indo-Tibetan Border Police at Choglamsar in Leh.

When Ladakh became a Union Territory, GeM (Government e Marketplace) registration was made mandatory for such businesses. For an uninitiated small trader like Bardi, the process was “too complicated”. His supplies stopped overnight. At any rate, he says, he was “no match for the more resourceful and tech-savvy contractors who rushed in from all over India”. GeM now is thrown open to all.

“They are selling toner for computer printers at a throwaway price of Rs.1,000 as they manufacture it themselves. We sold it for Rs.3,000 after adjusting procurement and conveyance costs. There was only one option available to us: shutting our shop,” said a crestfallen Bardi.

Bardi has now opened a mobile repair outlet; his monthly income is down to Rs.20,000, which is insufficient to support the education of his two daughters at the reputed Mission School and to look after his 80-year-old dependent father. He has twice defaulted on his loan and the bank is threatening to take action.

While people like Bardi struggled to make ends meet, the annual funds of the Union Territory government were lapsing every year, said Siddiq Wahid, a Ladakhi historian, who blames it on the “sheer incompetence of a top-down regime”.

Neglect of tourism sector

The neglect of the tourism sector, a significant contributor to Ladakh’s economy, attests to the underutilisation of funds. Indigenous hoteliers and filmmakers like George Odpal say Ladakh, with its stark mountains and alpine meadows, is as captivating as Uzbekistan and Kyrgyztan, where filmmakers have been flocking with their crews. “But few come here,” Odpal complained when Frontline met him at his two-storied studio at the entrance of Saboo, a village with 200 inhabitants, 20 km east of Leh.

“We need better and affordable connectivity from Mumbai, state-of-the-art infrastructure, and, at least initially, generous rebates, to attract filmmakers. But the Union Territory administration is yet to plan anything,” said Odpal. He believes that private consultancies should take over the tourism sector in Ladakh. His business is dwindling; in 2022, he hosted four big shooting crews, this year only one so far.

Blinding sunshine pours in from a cluster of windows that offer a panoramic view of Leh’s barren but splendid landscape: twisting, dusty plains that rise and fall steeply along imposing mountains. There are concrete houses and copses of drying poplars but no factories and hardly any hint of other vegetation. It is not hard to imagine why people here are sensitive about tourism, and desperate for government jobs.

The Union Territory administration has been unwilling to expand tourism to border areas. It closed down Hanle, a superb high-altitude sanctuary for stargazing, to foreigners. These moves betray the magnitude of the challenge India faces at the Line of Actual Control after China pushed troops inside Ladakh in 2020, leading to violent confrontations on the Galwan river area and Pangong Tso, a glacial lake at an altitude of 14,000 feet; 20 Indian soldiers and four Chinese soldiers were killed in the combat. The Himalayan frontier has since seen a massive build-up of troops by both countries.

The government has resorted to a tactic of simple denial, with the Prime Minister saying “not an inch of land was lost”. But various media have reported that India no longer has access to 26 of 65 patrolling points in eastern Ladakh.

Congress leader Rahul Gandhi, who visited Ladakh recently, sounded a warning: “The locals here are concerned about China taking our land. They have said that the Chinese troops took away their grazing land.”

At Merak, a picturesque village near Pangong, Tsewang Rigzin was among those who were witness to the catastrophe of “war”. Merak is part of the Changthang plateau, where the rare pashmina, or Changthangi, goats are found. But Ladakh lacks manufacturing units, so the wool is sent to the Kashmir Valley, where traditional artisans process it to make exquisite shawls, scarves, and wraps.

Chinese incursion

Rigzin said that after China’s incursions in 2020, the pastoral land at Fingers 4 and 5 were no longer accessible, forcing him to sell his goats at a throwaway price. When he is unable to eke out a living there, which is often the case, he and his Tibetan wife, Chiame, retreat to the plains, to a Tibetan neighbourhood, close to Choglamsar in Leh.

His knowledge of “amchi” comes handy there, yielding him enough money to support daily expenses. “Amchi” is traditional Ladakhi medicine, similar to Ayurveda, passed down over generations in the Tibetan plateau. Others are not as lucky and suddenly find themselves reduced to penury. Their story remains untold as the government obfuscates the happenings at the border.

Konchok Stanzin, councillor of Chushul, confirms India’s loss of land. “Earlier, our troops patrolled till Finger 8. China patrolled till Finger 4 on our side, escorted by the [Indian] Army. But now, maximum area has become buffer zone. The Army is unable to patrol even Fingers 3 and 4,” he said.

The nineteenth round of the India-China Corps Commander level meeting was held on August 13 and 14. A joint statement said the two sides had agreed to resolve “remaining issues along the Line of Actual Control” in eastern Ladakh in an “expeditious manner”. But as China continues to build massive infrastructure at crucial posts, there is a flutter of anxiety among the villagers that the full scale of China’s belligerence is perhaps yet to unravel.

Siddiq Wahid, a distinguished voice in Sino-India relations, said it was difficult to predict the PLA’s (People’s Liberation Army of China) tactics. “It is not war. It is to contain India as a regional power unless it accepts Beijing’s hegemony. It will largely depend on how India exercises its choices in the emerging new bipolar world.”

The struggles of living in a remote place, now beset by a hostile neighbour, vanishing jobs and businesses, and a steady trickle of outsiders who threaten to invade Ladakh’s cultural mooring have created a sense of foreboding in people. This manifests itself in a stream of questions about their identity and allegiances, about freedom and resistance, about contemporary nationalism and its dangers, all of which build off one another.

Over a lavish dinner at the banquet hall of the Grand Himalaya hotel, Zahir Bagh, a photojournalist from Kargil; Ziauddin, a former neuro-scientist; and Sajid, a local resident, ruminated on the question that troubles every Ladakhi today: The question of survival. Without the Sixth Schedule “we will go bankrupt”, they said.

Ziauddin, whose father owns the hotel, explained that even renovating a hotel would take anywhere up to Rs.7 crore, and while that might be a paltry sum for businessmen in New Delhi and Mumbai, for Ladakhis it represented generations of savings. “If private players from big cities enter our tourism sector, our hotels will disappear altogether,” he said.

Night descends heavily in the high-altitude desert, with the temperature dipping sharply and turning the mountain range into an ominous silhouette that captures the current state of mind in Ladakh: Restless. Angry. Losing faith in the government.

“Think of the impact on mental health,” Zahir said, pointing to the increasing use of drugs among the populace.

Much will depend on the implements that the BJP has in its toolkit for Ladakh. If it includes force and coercion, it might do to the Ladakhi people what their proximity to Kashmir’s 30-year-old separatist theatre did not: Erase their sense of belonging.

(Anand Bhakto is Senior Assistant Editor at Frontline. Courtesy: Frontline magazine.)