Introduction

Even as a given conjuncture of historical circumstances creates conditions for the rise of influential leaders and statesmen, the present has its own uncanny ways of retrieving the glory of the past leaders and invest them with new iconography and symbolism. In the process, long neglected leaders become new rallying points for public adoration and mobilisational energy. They get (mis)appropriated by new constellations of interests and get retrospectively invested with contemporary ideological charge. They also become part of official commemoration and turn out to be sources of political legitimation for competing political blocks. Their statutes and busts start growing in numbers, their birth and death anniversaries start getting celebrated with gusto, and their names get lent to roads, colleges, schools, buildings, government schemes and the like to perpetuate their memory. Politicians of the day vie with one another to forge real or imaginary associations with such past leaders and their ideology and try upstaging one another through photo-ops offered by a plethora of functions and events organized in the honour of such great souls.

Karpoori Thakur (24 January 1924 – 17 February 1988) is a case in point. The announcement of caste survey by the Government of Bihar has brought back Karpoori Thakur on the national stage in an unprecedented way. The commentariat is busy finding elements of visionary farsightedness in the reservation policy that Karpoori Thakur introduced in 1978 as the then Chief Minister of Bihar (24 June 1977 – 21 April 1979). In particular, his categorisation of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) into two groups (Annexure I and II), that is Backward Classes (BCs) and Most Backward Classes (MBCs) has brought him so many laurels that any reservation policy alluding to the layered backwardness is now popularly referred to as Karpoori Thakur formula. In ideological terms as well, Karpoori Thakur is being re-invented as a great socialist leader who was able to carry forward the legacy of socialist veterans like Jayaprakash Narayan and Rammanohar Lohia. His decision to do away with English as a compulsory subject for the Matriculation curriculum in Bihar as Education Minister in 1970 is seen as a committed ideological act a la Lohia to undermine the supremacy of the English language. Interestingly, his first chief ministership (22 December 1970 – 2 June 1971), though short-lived, was politically significant as this was made possible with the support of the then Bharatiya Jana Sangh (Singh 2015). Indeed, this ‘pragmatic’ alliance between the socialists and the Jan Sangh had happened earlier as well. In fact, Lohia’s politics of anti-Congressism facilitated an alliance between the socialists and Jan Sanghis in two crucial parliamentary by-elections in 1963: in Jaunpur where the then Jana Sangh president Deen Dayal Upadhyay won and in Farrukhabad where Rammanohar Lohia emerged victorious (Thakur 2000). Subsequently, the anti-Congressim served as a major coalitional (if not ideological) plank facilitating the formation of Samyukta Vidhayak Dal governments in nine states in the elections of 1967 [1]. Not surprisingly, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is as busy celebrating Karpoori Thakur as the ruling JD-U-RJD dispensation in Bihar. Be that as it may, a centennial appraisal of Karpoori Thakur is appropriate enough for us to understand the contemporary political configuration in Bihar and beyond.

Reservations: Caste and Backwardness

Karpoori Thakur’s political identity revolves around caste-based reservations something that has acquired increasing policy resonance with the passage of time. The Bihar caste survey is but of piece with the growing politics of competitive backwardness unleashed in post-Independence India. In no way, demands for reservations emanating from various groups and communities should be seen as sudden revival of an old and forgotten issue in contemporary political discourse. Karpoori Thakur’s implementation of the policy of reservation for the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in Bihar (as per the recommendations of the Mungeri Lal Commission, 1971-1976) in government/public employment and educational institutions at the state level in 1978 has been hailed as a transformative moment in the politics of reservation in India. True, for the first time, there was an administrative acknowledgement of the graded nature of social backwardness across jatis in two annexures. Moreover, there was conscious inclusion of various Muslim caste groups in the Bihar state OBC list. Also, there were quotas women (irrespective of caste) as also for poor among the high castes (EWS in the current parlance). Viewed thus, Karpoori Thakur surely deserves enormous credit for having not only conceptually innovated with the scope of social backwardness but also for displaying immense political courage in implementing reservations at a time when high-caste groups controlled key levers of social and political power in Bihar. Expectedly, the implementation of the OBC reservation policy led to large scale violence in the state and ultimately cost him his chief ministership in 1979 (Thakur and Bhattacharjee 2023a).

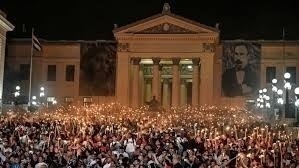

The implementation of the OBC reservation in Bihar in 1978, albeit much delayed when compared to states like Tamil Nadu, propelled Karpoori Thakur to be one of the tallest leaders in post-independence Bihar. Equally, his political and ideological influence has been prodigious which, in effect, is quite disproportionate to his actual years in office as the Chief Minister of Bihar (less than two and a years cumulatively). Expectedly, Karpoori Thakur continues to occupy much of popular political imagination in Bihar. The growing number of Karpoori Vichar Manch across the length and breadth of the state, a forum espousing and disseminating Karpoori Thakur’s political and ideological programmes is an indicator of his posthumous popularity. In recent times, there has been much fervour to celebrate his birth (24 January) and death (17 February) anniversaries including by the official state establishment. Metaphorically speaking, it is difficult to conceive of leaders like Lalu Prasad Yadav, Ram Vilas Paswan and Nitish Kumar without acknowledging and appreciating the kind of politics that Karpoori Thakur envisioned and espoused. Justifiably enough, there are demands for the conferment of Bharat Ratna on him from all kinds of political quarters. As it happens so often, public memory focuses on the positive elements of the legacy of a politician-statesman leaving out of discussion and debate more controversial aspects of the same. Indeed, we do not hear at all about Karpoori Thakur’s endless squabbling within the larger socialist tradition and his joining, breaking away and re-joining a long list of political parties with short-lasting names. But then, the internecine conflicts among Indian socialists have been, so to speak, their most lasting attribute, giving rise, in turn, to dozens of parties ever since the founding of the Congress Socialist Party in 1934. And, therein lies the sad tale of continuous shrinkage of the scope of social justice – which in early Indian socialist thought included a substantial component of economic justice – and its ultimate evolution as a program solely articulating the need for caste-based proportionate representation in admissions, jobs, and so forth, a process sanctified by the Mandal Commission recommendations and their implementation in 1990 by the then V. P. Singh (central) government.

Socialists and Social Justice

Sure enough, in the initial decades after Independence, the socialists championed an agenda of social justice which was, quite correctly, mindful of the concerns of equity and economic well-being of the masses. Undoubtedly, social justice then encapsulated much more than the currently prevalent idea of social justice qua caste-based quota/reservation. The socialists consistently focussed on the rights of the tenants, agricultural labour, zamindari abolition and the general alteration of the structure of socio-economic power in the countryside. In short, the economic justice was an indispensable part of the politics of social justice that socialists have been the votaries of. It is not for nothing that the Bakasht movement in Bihar was largely led by the socialists. Likewise, they were prominent participants in all the major peasant movements in the state. Leaders like Ramnandan Mishra, Suraj Narayan Singh, Rambriksha Benipuri were active in socialist politics and were influential kisan leaders in their own right. Most of them were frontrunners in the Quit India movement of 1942, a movement that also politically baptised Karpoori Thakur. However, in due course of time there appears to have developed a division of political labour whereby economic issues like the rights of tenants, minimum agricultural wages, distribution of surplus land etc. became the preserve of the Communist Party of India (CPI) and its later offshoots, while the socialists of all hues started digging in the legacy of the Triveni Sangh, an organisation established in 1934 by representatives of three dominant backward castes of Bihar, namely, Yadav, Koeri and Kurmi, to demand proportionate reservations in jobs for the backward castes. Rammanohar Lohia’s slogan of sau me sath (indicating that 60 per cent of population belong to OBCs) further strengthen an idea of social justice anchored in caste-based proportionate demographic reservation (Thakur and Bhattacharjee 2023b).

Arguably, the politics of anti-Congressism of Ram Manohar Lohia provided a discursive legitimacy to this ongoing process of systematically undermining the significance of the economic in political projects of social transformation. All the same, capturing state power (rather snatching it from the Congress) turned out to be the prime motivation of socialist politics. The earlier capaciousness of social justice was made reducible to caste-based reservations alone; it was as if nothing else mattered except for the limiting agenda of representational parity among various groups and communities defined in the idiom of castes. Social backwardness came to stand for a constellation of newly assertive caste groups with mobilisation prowess. Political machinations of cobbling majority on the floors of parliament and legislative assemblies led to shifting alliances among various self-styled caste leaders. Political instability (volatility) became the new normal. It is noteworthy that Karpoori Thakur was the Chief Minister for just six months in the much-celebrated wave of anti-Congressism in north India in the aftermath of 1967 assembly elections, and that too with the support of the defectors from the Congress.

In any case, this decline of the economic in socialist politics in Bihar is inconceivable unless one factors in Karpoori Thakur’s influential role in reconfiguring that politics for the sake of political expediency. Substance gave way to symbols. Social justice became a rhetorical end in itself without necessitating any structural change in governance or developmental priorities. Indeed, the rhetoric of social justice did yield tangible political pay-offs. Otherwise, how would one explain Lalu Prasad Yadav’s seamless control of political power for fifteen long years (1990-2005)? Or, the continued presence of Mahagathbandhan in power in the state?

Unfortunately, though, the social justice parties in states like Bihar failed to create the kind of impact on policy and governance which Kalaiyarasan and Vijayabaskar (2021) term the Dravidian Model drawing from the politico-economic experience of Tamil Nadu. Even otherwise, the disconnect of the social and the economic lies at the centre of perfunctory politics of social justice that leaders like Karpoori Thakur practised under the overall Lohiaite ideological influence. Put differently, this politics contributed to the complete depletion of the economic contents of social justice rendering it ideologically vacuous, administratively ineffective and socially divisive.

The non-implementation of the Bandyopadhyay Commission report since 2008, and the complete silence of social justice parties, is evidence enough of the decline of economic issues on the political agenda of the socialists. The point is that the champions of social justice remain assured of their political constituency even if they wilfully ignore a fundamental economic issue like the distribution of Bhoodan land which has a bearing on the life chances of the majority of the poor population. The latter is politically fragmented, and more often than not, articulate their collective interests in communitarian idioms and echo identity politics of their political masters.

The contemporary indifference to the land question in a state like Bihar by the political class is symptomatic of the larger recasting of political space in Bihar. Over the last few decades, the apparent successes of the politics of backwardness have rendered struggles relating to the ownership, control and use of land politically less attractive. The gradual eclipse of land-related struggles explains the firm anchoring of the newly found politics of social justice into caste idioms. And the latest announcement by the Government of Bihar to raise caste-based quotas to 65 per cent in the light of caste survey is the apogee of politics around reservations that the socialists initiated with unparalleled zeal and that has now turned out to be policy common sense of the day. Undoubtedly, Karpoori Thakur’s politics of caste-based quota precipitated the debilitating conceptual divide between struggles for social and economic justice. The idea of social justice was rendered narrower in scope to be assessed merely in terms of caste-based proportional reservation in elected bodies, admissions to public educational institutions and public employment. In the process, socialists lost much of their initial political agenda that had given their politics a transformative edge in the earlier decades after Independence (Thakur and Bhattacharjee 2020). Lalu Prasad Yadav’s ascendance on the plank of social justice was then already narrowly circumscribed by one of the tallest socialist leaders in Bihar (Thakur 2013). Little wonder, Lalu Prasad Yadav could politically sustain his rhetoric of social justice for decades without even a feeble gesturing towards the agenda of land reforms. And more recently, Nitish Kumar has become the ultimate game changer after his announcement of the caste survey without anyone pointing finger at him for sitting over the Bandyopadhyay Commission Report for full fifteen years. Amidst the euphoria generated around caste surveys and census across the country, it is time we re-visited Karpoori Thakur and his politics with the larger aim of understanding varying regional political trajectories of social justice in the country. Sadly, there is not much on him for the English reading public. One only wishes that someone writes a short biography in his centenary year.

References

Jaffrelot, Christophe. 2003. India’s Silent Revolution: The Rise of Low Castes in North Indian Politics. Delhi: Orient Longman.

Kalaiyarasan A. and M. Vijayabaskar. 2021. The Dravidian Model: Interpreting the Political Economy of Tamil Nadu. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Singh, Jagpal. 2015. ‘Karpoori Thakur: A Socialist Leader in the Hindi Belt’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 50, No. 3, 17 January, pp. 54-60.

Thakur, Manish and Nabanipa Bhattacharjee. 2020. ‘Peasants and Their Interlocutors: Swami Sahajanand, Walter Hauser and the Kisan Sabha’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 55, No. 20, 16 May, pp. 24-28.

Thakur, Manish and Nabanipa Bhattacharjee. 2023a. ‘Karpoori Thakur: Social Justice and Its Limits’, Mainstream, 14 October

Thakur, Manish and Nabanipa Bhattacharjee. 2023b. ‘Socio-economic Takeaways from Bihar Caste Survey’, The Tribune, 10 October.

Thakur, Manish. 2000. Rammanohar Lohiya and the Politics of Anti-Congressism’, Mainstream, March 25, pp. 9-10.

Thakur, Manish. 2013. ‘Land Question in Bihar: Madhubani as a Metaphor’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 48, No. 19, 11 May 2013, pp. 19-21.

Notes

[1] Samyukta Vidhayak Dal was a coalition of parties formed in several north Indian states after the 1967 assembly elections. This primarily consisted of the then Bharatiya Kranti Dal. The Samyukta Socialist Party, the Praja Socialist Party and the Bharatiya Jan Sangh. They posed the first major political challenge to what the political scientist Rajni Kothari had called the Congress System. In the 1967 elections for legislative assemblies the ruling Congress Party was defeated in the following states: Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Punjab, West Bengal, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala (Jaffrelot 2003).

(Manish Thakur and Nabanipa Bhattacharjee teach sociology at IIM Calcutta and Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi respectively. Courtesy: Mainstream Weekly.)