‘Dhaai Aakhar Prem’: A One-of-a-Kind Public March

Newsclick Report

In today’s day and age, the idea of walking across villages on foot, staying there, trying to understand regional music, dances and arts and trying to convey one’s messages through songs and hand woven gamchhas, what can it be other than an obsession or a passion?

But this passion has led to the envisioning of an awe-inspiring journey spanning the whole country. People from different cities and regions met, tried to find the root causes of the decay, hatred and dejection felt all over the society. In this process, one’s own shortcomings and flaws were also taken into account. All this culminated into the same old answer, like Gandhi said, “Go to the people, go to the villages.”

This way, a one-of-a-kind journey was envisioned which received its name from Kabir’s Dhaai Aakhar Prem (two and a half letters of love), which drew inspiration from Gandhi. The goal of the march is to create a country and society along the vision of revolutionary youth like Bhagat Singh, build a society based on equality and love.

Slowly and steadily, the idea gained ground and people started joining in on their own. From different quarters, people like Gandhiji’s great grandson Tushar Gandhi, and Uttar Pradesh’s famous poet and former parliamentarian Uday Pratap Singh sent their messages of solidarity. In Mumbai, the likes of actor Manoj Bajpayee, film director Anurag Kashyap and even late actor Irrfan’s son Babil Khan came forward while people’s support is being gathered in West Bengal, Rajasthan, Kerala, Kashmir, etc.

The march had to take a concrete and systemic form, so writers’ organisations, cultural organisations, students-youth of the country altogether held a meeting and decided to begin this march on September 28, on the occasion of Bhagat Singh’s birth anniversary. The march is scheduled to begin from Rajasthan’s Alwar district and sequentially cover every region to conclude its first leg on January 30, which marks Gandhiji’s martyrdom day (the day he was assassinated by Right wingers).

Before this, a collective event will be held in the national capital on September 27, the eve of Bhagat Singh’s birth anniversary, which will be attended by the peace-loving people of Delhi including teachers, students, scientists, journalists, culturalists, etc.

The main attraction of this event will also be a ‘Gamchha Show’. While preparing the structure of the public march, it was felt that relentless privatisation and mechanisation had acutely increased unemployment in the country and reduced the dignity associated with labour.

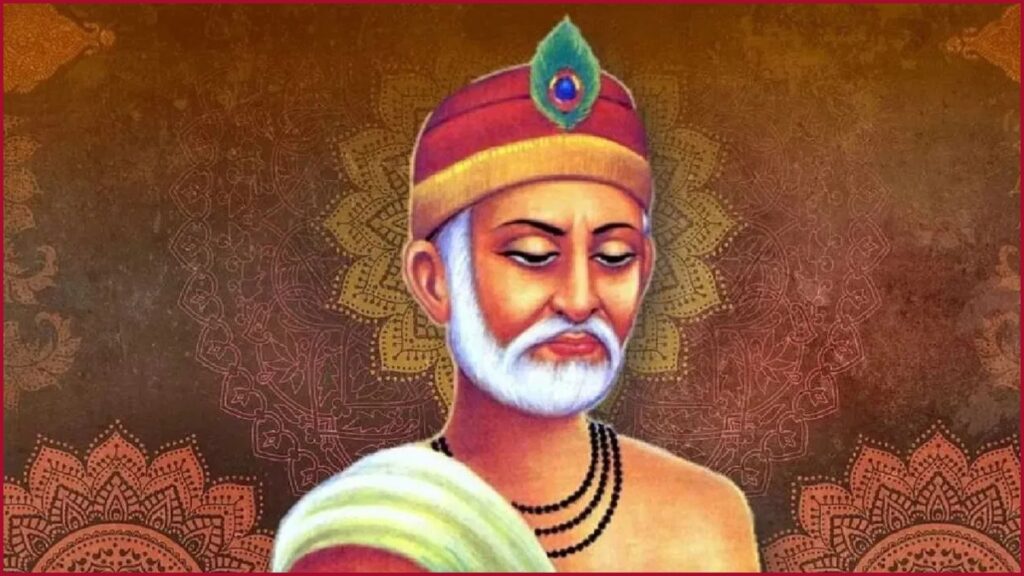

This is why a hand-woven gamchha has been selected as a symbol for this yatra. Great reformers, such as poet saints like Kabir and Ravidas, were able to fearlessly question those in power because they weren’t dependent on anyone. They earned money from their labour and this is what gave them their humility and self-respect.

The gamchha is a symbol meant to evoke respect for labour against inhumane mechanisation. The self-reliance of a worker is like a ray of hope in these times of social decay, unemployment and hatred.

Across the country, artistes are making posters with the march’s message, singers are writing songs, culturalists are preparing plays. History is being scoured for leaders of love such as Kabir, Ravidas, Bhagat Singh, Vivekanand, etc. Karnataka’s Basavanna, Tamil Nadu’s Periyar, Maharashtra’s Jyotiba Phule and Punjab’s Bulleh Shah are all being revisited. People from far off places are filling the registration form to participate in the yatra.

Although the registration is not so simple, there are certain basic conditions for those who want to register and join the march– any kind of intoxication is prohibited, one has to listen to the people more, and maintain the greatest value of simplicity, etc.

A group of youngsters have made a whole website and social media pages where all information about this march is available.

Even though the whole journey is relying on the goodwill of villagers for food and lodging arrangements, the organisers have ordered hand-woven gamchhas from weavers across India to fulfil the extra expenditure. The organisers will present them to those who support the yatra. They are also appealing to those who can, to buy 10-15 or as many gamchhas as they can afford. This will generate direct income for weavers. They will also provide these gamchhas for a small token amount for those people who are unable to afford it.

The dates and routes for the march in every state have been decided, and one-day marches will also be continually held in every state’s districts.

The unique thing about this march is that it will cross the memorials, homes and workplaces of important poets, writers, social reformers, leaders of the Independence struggle, etc. It will reach its destination with the message that a variety of struggles have been waged to weave the country and society with love and equality. And that we will save this diversity, these priceless struggles and sacrifices, the labour of the toiling masses and the love of this beautiful country. We will forever sing the song of “Dhaai Aakhar Prem.”

(Courtesy: Newsclick.)

Book Review: Discovering Indigenous Modernity in the Words of Kabir

Harbans Mukhia

Purushottam Agrawal has been trying to unearth the layers of meanings in the weaver-poet-philosopher Kabir ever since his student days at JNU. Over the past 40 years he has released two masterly books, Akath Kahani Prem Ki: Kabir ki Kavita aur Unka Samay (2009) and now Kabir, Kabir, which open a small window to the immensity of an epoch-encompassing vision of the poet.

At a time when the academic world was abuzz with a sharply critical scrutiny of the virtually closed notion of modernity as a gift of the West from the 18th century on to itself and to the rest of humanity, Agrawal posited the notion of deshaj adhunikta, indigenous modernity in the creation of which Kabir was a major presence even as he was part of a process. He has now taken this proposition, suggested in his Akath Kahani, to a fully structured argument, based on a vast spectrum of sources – from history, theology, sociology, philosophy, anthropology and of course literature evident from his references and discussion in the text, although his bibliography fights shy of including all these in the list.

Agrawal is almost waging a war against the dominant academic, and far more important, cultural paradigm that the ‘meaning of India’ is located almost exclusively in its Sanskrit texts to which additions were made by Persian texts of the medieval Indian courts and the image of modern India is drawn from the English language discourse; what falls by the wayside is the amazingly dynamic India that rests in the vernaculars. It is this image that Agrawal seeks to retrieve from the dustbin and bring to frontlines. And he does so with great power and elegance.

It is over the past around three decades that the world woke up to the idea that the modern world we inhabit was not exclusively the creation of the West through its overthrow of its own medieval ‘dark age’ by finding a way out through the discovery, or rediscovery, of rationality which lies at the base of ‘modernity’; the West then felt obliged to wipe out the dark age of the rest of the world through its benign hand of colonialism. This was a conclusion lying ‘out there’ in C.A. Bayly’s words in his last and masterpiece of a book Making of the Modern World; its universal visibility itself ensured its proof against any sort of questioning.

But Bayly himself, and numerous others, including some like S.N. Eisenstadt who had earlier subscribed to its security against questioning, had opened up the massive theme of ‘modernity’ to intense interrogation. It did not take long to realise that the ‘modern’ world we inhabit had evolved not in one of its provinces, namely Europe, nor in a limited frame of time, between 17th, 18th and 20th centuries; indeed all societies and all civilisations had contributed to its evolution through all periods of human habitation in one way or another: in the way of creating and developing different ideas, philosophies, religions, forms of governance, engaging in commerce, crops, crafts, forms of resistance, literatures… the list is endless. ‘Modernity’ has decisively been decentered from its Western axis and has given way to ‘modernities’ in numerous contexts.

It is in this contentious milieu that Kabir, Kabir makes a strong intervention. Incidentally the repetition of his name in the title is taken from a verse of his own reproduced ahead of the text. Kabir’s deshaj adhunikta lies in his construction of a conceptual alternative to religious or communal tensions following the arrival of Islam in India. Inter- and intra-religious conflicts soaked in blood were far less marked in India’s medieval age than in the West, but Kabir was neither aware nor concerned with the West’s problems; for India, in lieu of the existing dichotomy between denominational religions – Hinduism and Islam – and competing gods – Allah and Ishwar – he created a substitute dichotomy between a universal religiosity/spirituality and a universal God. This God was neither Ram nor Rahim; he was as often both Ram and Rahim.

Ram is his normative or stylised noun for him, but he was not the son of Dashrath or the king of Ayodhya. He was not a person but a pervasive, universal presence beyond time, space and identity, Brahman. Love, the equivalent of bhakti, for him was itself a universal and timeless and thus frictionless worship; bhakti that is inside of each human being and does not reside in the namaz or the puja, in the temple or the masjid.

This was a brilliant alternative in the whole era marked by sectarian and religious friction emanating from denominational identities; its influence on all layers of society from the field to the court, from the cultivating peasant to the outstanding intellectual like Abu’l Fazl was remarkable. Akbar’s and Abu’l Fazl’s renowned rational policy of sulh-i kul had Kabir’s dichotomy at its base. Guru Granth Saheb has incorporated some 225 verses of Kabir and Rabindranath Tagore translated a hundred of these with great admiration. An outstanding she’r of Ghalib is a near verbatim rendering of Kabir’s philosophy. It is Kabir’s notion of a single inclusive God in lieu of two competing gods that is invoked by the most ordinary to the most extraordinary Indians like the Mahatma in our everyday life and have done so over 600 years.

This was the indigenous or vernacular modernity that Agrawal seeks to highlight with power and combative passion. He also adds other elements of ‘modernity’ to it: the recognition of the individuality of the individual and the role of ever growing commerce in expanding the spread of ideas.

The notion that respect for the individual’s identity comes to us with modernity, i.e. with capitalism and that pre-modern regimes recognised the family rather than the individual as the basic social unit has been under considerable strain of late. It is just as well that Agrawal brings attention to this facet. He also lays great emphasis on the spread of commerce as almost the chief agency of the expansion of deshaj adhunikta in his earlier work as well as in the current one.

The problem with the centering of commerce as the driving agency is its treatment as an independent variable, for commerce is incapable of being one. The expansion of commerce presupposes the expansion of the production of commodities which is predicated upon expansion of both the means of production and of labour or alternately technological innovation which would raise the productivity of land (or factory) and labour which requires several other inputs, in particular investment.

Expansion of commerce would result from these multifarious developments. It is only in our age of stock market trade that wealth can grow independently of the production base; medieval times everywhere witnessed impressive levels of economic growth and expansion of production as well as commerce; in India this was phenomenal which put India in control of just about 25% of the world’s GDP at the beginning of the 18th century at the height of the Mughal empire, never mind its image as India’s dark age in colonial historiography and the “history” doled out on TV channels and WhatsApp university.

If Agrawal had placed his expansion of commerce in the context of the expanding economy and the security afforded by an expansive, strong and effective state and its administrative institutions instead of focusing almost exclusively on commerce, his argument would have acquired an enhanced persuasive power. Nevertheless, this book, along with the earlier one, does make a strong case for bringing the great cultural vibrancy of vernacular wisdom centre stage along with the elite languages to explore the idea of India.

(Harbans Mukhia taught medieval history at JNU. Courtesy: The Wire.)