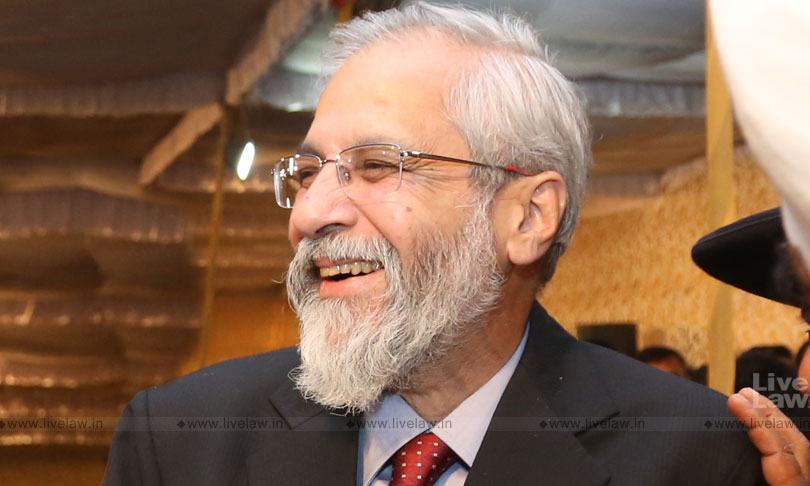

(Below is the Full Text of Seventh Sunil Memorial Lecture delivered by Justice (Retd) Madan Lokur on November 29, 2020)

Good evening Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is indeed a privilege to deliver the Sunil Memorial Lecture for this year to an august audience consisting, among others, of academics, intellectuals and professionals from different disciplines and interests. I thank the Sunil Memorial Trust for this privilege.

Sunil did his post-graduation from Jawaharlal Nehru University in Economics. He was a brilliant student who topped his class and even otherwise had a stellar academic record. His commitment to marginalized sections of society compelled him to move to rural India and become a full-time activist following the ideas and ideals of Gandhiji and Lohia. His principal work was at the ground level and among the adivasis of Madhya Pradesh. He was a proponent of decentralization of power, rejuvenation of the rural economy, local populations’ control over natural resources and an egalitarian society. He was a prolific writer and wrote extensively on socio-political issues mainly in Hindi newspapers and magazines. He had a keen interest in issues concerning the environment which he considered an important element of a sustainable and egalitarian society.

Unfortunately, he passed away at a comparatively young age of 54 but accomplished and achieved a lot thereby becoming an important link between people’s movements and its progressive intelligentsia. His contribution to an alternative to mainstream politics was immense. Today’s lecture is in Sunil’s honour and is dedicated to him.

Introduction

I propose to present my views on three topics and their treatment by the judiciary in India. The three topics are social justice, dignity and personal liberty with a sub-text on human rights and frights. These topics, I am sure, would have been close to Sunil’s heart.

Till a few years ago, the Supreme Court gave considerable importance and significance to social justice, human rights and the dignity of the individual, but I am afraid some of these thoughts are now on the back burner for reasons that future historians will identify for us. Today, we have to make do with observations and pious platitudes and try our utmost to bring the focus back on the dignity of the individual through a recognition of human rights and socio-economic justice.

Social justice issues

First on social justice issues: The Preamble of our Constitution states that we, the people have resolved to secure social justice to all citizens. The onus is therefore on us to ensure that all citizens are the beneficiaries of social justice in the manner provided by the Constitution. While it is not easy to define social justice or identify its constituents, my idea of social justice is encapsulated in Article 14 of the Constitution, that is, equality before the law or equal protection of the laws including marginalized sections of society. The Constitution postulates some exceptions, for example, Article 15 provides that “Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any special provision for women and children.” There are valid reasons for this exception, as indeed for providing reservations for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes in services under the State.

What have we, as a people, done to deliver social justice to some marginalized sections of society?

Firstly, some social security laws have been enacted by our representatives but not implemented in letter and spirit by the Executive. This came to the fore in a public interest litigation filed by Swaraj Abhiyan. I had occasion to preside over the Social Justice bench of the Supreme Court and we were required to look into the implementation of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005. On most dates of hearing, the grievance voiced by Swaraj Abhiyan was the failure of the Central Government to release funds for the smooth functioning and operation of the employment guarantee scheme, such as failure to provide 100 days guaranteed employment. On these occasions, the constant refrain of the government in the Supreme Court was that sufficient funds are not available or that they would be released in a few weeks. This resulted (on the one hand) in denial of work and denial of wages to lakhs and on the other hand, work being taken from lakhs of people across the country virtually without wages since the payments were more often than not delayed by several weeks. The law provides that if the wages are not paid within 15 days, the beneficiaries would be entitled to interest, but I don’t recall any instance where interest was paid on delayed payment.

Another example of a social justice law having been enacted but not implemented in letter and spirit is the National Food Security Act, 2013. This requires every State government to constitute a State Food Commission to monitor and review implementation of the law but what we found was that many State governments had not done so, thereby denying social justice to the impoverished and hungry.

The worst affected by the insensitivity of the State to implement socially significant laws have been children and construction and building workers. As far as children in need of care and protection are concerned, they are supposed to be looked after in homes that are registered in accordance with law. In a public interest litigation, it came on record that a large number of these children’s homes had not been registered even though the Juvenile Justice Act had been in place for several years. This necessitated an order for conducting a social audit for an assessment of all such institutions. More than two years have gone by since then and a recent report of the National Commission for the Protection of Child Rights, based on the social audit, has revealed that 28.5% of the children’s homes or 2039 children’s homes had not been registered. Equally frightening is the report that 38% or 2764 of these child care institutions did not have adequate measures to prevent any form of physical and emotional abuse of children. It is for this reason that there are reports coming out virtually every month of child sexual abuse and so on.

Construction and building workers have been off the radar of the establishment for several years. A cess is collected for their benefit on the cost of construction incurred by an employer. This is provided for by the Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Cess Act, 1996. This cess is intended to be gainfully utilised by a welfare board for the benefit of building and other construction workers. Even though the law is about 25 years old, it has not been implemented as it should be, in spite of directions given by the Supreme Court. On being asked, it appeared that some of the welfare boards had utilised the cess for the purchase, among other things, of washing machines and computers. How these purchases benefit building and other construction workers remains a mystery. We saw during the recent lockdown the adverse impact of non-implementation of the law on these hapless individuals, called migrants, when thousands and thousands had to walk hundreds of kilometres to reach home. Worse still was the amazing attitude of the State which informed the Supreme Court, through the Solicitor General, that as of 11 am this morning, that is 31st March, nobody is on the road!

Instances like these clearly indicate that while social justice may be on the agenda of Parliament, it is certainly not on the agenda of those authorities that govern us. Unfortunately, the preamble to the Constitution has been reduced, to a fairly large extent, to a pious platitude with little hope of redress.

There is a second category of marginalised and disadvantages sections of society where we have not even enacted social security laws. I would like to cite three examples, by way of illustration. Firstly, the plight of thousands of widows in Vrindavan, Varanasi, Jagannath Puri and several other places. Their living conditions raise socio-economic issues not governed by any law. Many, if not most of these widows live in abject poverty with no source of income or means of sustenance. The Social Justice bench of the Supreme Court dealt with the living conditions of widows in Vrindavan. It was found that the day of many of these widows would begin with chanting prayers in a temple which earned them their breakfast. Their lunch and dinner were also taken care of by the chanting of prayers in a temple. Occasionally, they were the beneficiaries of alms doled out by those seeking divine grace. The nights were spent in what could loosely be called an ashram or a dharmashala, and so life went on. They too are human beings, but many are treated as social outcasts and some face psychological problems.

A second example is that of brick kiln workers. Lakhs of them are living in conditions that would shock the conscience of any reasonable person. Their working conditions are even worse. There is a recorded instance of some persons who had been given an advance for working in a brick kiln in a particular State. However, they were taken to another State along with a few others. They refused to work in that State and actually ran away. Unfortunately, two of them were caught and the contractor gave them the option of either having their hands or their legs chopped of. Eventually, their palms were chopped off, leaving them crippled for life. It is another matter that the contractor and his henchmen were prosecuted and sentenced but the question is why is there is no effective legal mechanism to regulate the plight of the marginalised and the downtrodden? Is our welfare State doing anything about it?

Finally, another instance where people on the margins are treated in a manner that brings shame to society is under trial prisoners. Again, there is no law governing their rights except jail manuals of doubtful vintage. The judiciary has been concerned about their rights for the last about 40 years but little has changed and there continues to be overcrowding in prisons, deaths attributable to unnatural causes and denial of access to justice. More recently, undertrial prisoners have had to face the dim prospect of their bail application not getting listed. After considerable running around, even if the application does get listed, bail is denied, in spite of the progressive bail jurisprudence developed over the years, and on the principal ground that the allegations are grave and serious, including meaningless charges of sedition and unlawful activities amounting to terrorism, often without any evidence, let alone cogent evidence.

In situations such as these, what is it that is expected of the judiciary? When it comes to social justice issues, particularly those concerning the marginalised, the distressed, the downtrodden and oppressed, the Supreme Court and indeed the entire judiciary must be alive and creative in interpreting the law for the benefit of the people and recognizing its mandate and obligations in public interest. If Parliament fails to legislate, or if it does legislate and the Executive does not faithfully implement the law, then the Supreme Court cannot fold its hands and plead helplessness. In the case of Mohinder Singh Gill [1] decided by the Supreme Court in 1977, it was submitted by the Election Commission that there were gaps which needed to be filled up for conducting free and fair elections. In response, the Supreme Court said:

“But where [laws] are absent, and yet a situation has to be tackled, the Chief Election Commissioner has not to fold his hands and pray for divine inspiration to enable him to exercise his functions and to perform his duties or to look to any external authority for the grant of powers to deal with the situation. He must lawfully exercise his power independently, in all matters relating to the conduct of elections, and see that the election process is completed properly, in a free and fair manner.”

The Supreme Court then quoted a learned author who said, and this is important: “An express statutory grant of power or the imposition of a definite duty carries with it by implication, in the absence of a limitation, authority to employ all the means that are usually employed and that are necessary to the exercise of the power or the performance of the duty…. That which is clearly implied is as much a part of a law as that which is expressed.” [2] The Supreme Court must heed what it has said more than 40 years ago.

Cynics may refer to this view as judicial activism and judicial overreach but given the circumstances, the judiciary has no option but to be proactive on issues concerning the well-being of those on the fringes of society. The judiciary cannot abdicate its constitutional mandate and responsibility. I am afraid, on an overall conspectus, a lot still needs to be done by the judiciary in this direction.

Dignity jurisprudence

About dignity jurisprudence: The Supreme Court has shown its creative side in several decisions, particularly in matters pertaining to human rights and for this, the Supreme Court has heavily relied upon article 21 of our Constitution. This article is very simple and straightforward. It provides that “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.” These few words have been given a dynamic and progressive interpretation such that it has become virtually the life blood of our Constitution and the basis for dignity jurisprudence, human rights and social justice.

Way back in 1981, the Supreme Court considered Article 21 and held that “the right to life includes the right to live with human dignity and all that goes along with it, namely, the bare necessaries of life such as adequate nutrition, clothing and shelter and facilities for reading, writing and expressing one-self in diverse forms, freely moving about and mixing and commingling with fellow human beings.” [3]

Over the last about four decades, this jurisprudence gained acceptability and strength through a series of decisions that touched the lives of the downtrodden, whether they were bonded labour, under trial prisoners, slum dwellers, the homeless on footpaths and indeed most marginalized sections of our society. The recent past saw two significant decisions concerning those who were treated as being on the fringes of society, if not outside society. I refer to the case of National Legal Services Authority or NALSA in 2014 and Navtej Singh Johar in 2018. In the NALSA decision, the Supreme Court gave recognition to gender identity and sexual orientation. The judiciary accepted that transgender persons constituted a third gender and that they too had equal rights. In arriving at this conclusion, one of the factors that weighed with the court was that the fundamental rights chapter in our Constitution referred to citizens and persons, and indeed, transgender persons were both citizens and persons and so were entitled to the same rights as anybody else. This was a great decision in favour of a community that was usually shunned by society.

However, in view of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which penalizes sexual activity “against the order of nature” consensual sexual activity amongst transgender persons and those of the LGBTQ community was not decriminalized and it continued to remain a criminal offence.

A major leap forward was taken by the Supreme Court in the Johar decision when it decriminalized consensual sexual activity amongst adults and recognized what it described as identity with dignity. While doing so, it was observed that “The LGBT community possess the same human, fundamental and constitutional rights as other citizens do since these rights inhere in individuals as natural and human rights.” The court went on to observe that:

“……. Section 377 Indian Penal Code does not meet the criteria of proportionality and is violative of the fundamental right of freedom of expression including the right to choose a sexual partner. Section 377 Indian Penal Code also assumes the characteristic of unreasonableness, for it becomes a weapon in the hands of the majority to seclude, exploit and harass the LGBT community. It shrouds the lives of the LGBT community in criminality and constant fear mars their joy of life. They constantly face social prejudice, disdain and are subjected to the shame of being their very natural selves. Thus, an archaic law which is incompatible with constitutional values cannot be allowed to be preserved.”

These progressive decisions provided some immediate gains. For example, unlike in the past, transgender persons could vote and contest elections as persons belonging to the third gender; a transgender person was appointed as a goodwill ambassador by the Election Commission and another became a spokesperson for a national political party and so on. Members of the gay community slowly but surely came to be accepted as equals in many places, including at the workplace.

While the dignity of transgender persons and members of the LGBTQ community has been recognized, and the right to choose a partner has been accepted by the Supreme Court, have we actually implemented these judgments and the constitutional provisions in letter and spirit? What was granted to the transgender community with one hand was partially taken away with the enactment of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019. It is not necessary to go into the details of this law except to note that it has been challenged in the Supreme Court. Like many other cases of importance, this too is pending adjudication.

As far as members of the LGBTQ community are concerned, the Supreme Court has not been able to walk the talk. It is quite well-known that a gay lawyer of outstanding ability has been recommended for appointment as a judge of the High Court but the collegium of the Supreme Court has yet to take a decision on forwarding his case for appointment even though two years have gone by. Are we, therefore, recognizing dignity of the individual from LGBT community only on paper, forgetting what our Constitution stands for?

Equally disconcerting is the dichotomy of views, and now a regression, is being witnessed in the rights of women and issues concerning their dignity. The Hathras rape and murder is very much in our thoughts. But I would like to travel a different path on dignity and go back to a decision given in 2006 in the case of Lata Singh in which the Supreme Court painfully observed in rather strong words:

“We sometimes hear of “honour” killings of such persons who undergo inter-caste or inter-religious marriage of their own free will. There is nothing honourable in such killings, and in fact they are nothing but barbaric and shameful acts of murder committed by brutal, feudal-minded persons who deserve harsh punishment. Only in this way can we stamp out such acts of barbarism.” [4]

This was followed by a more recent decision in the case of Shakti Vahini [5] where the court remarked that:

“Honour killing guillotines individual liberty, freedom of choice and one’s own perception of choice. It has to be sublimely borne in mind that when two adults consensually choose each other as life partners, it is a manifestation of their choice which is recognized under Articles 19 and 21 of the Constitution. Such a right has the sanction of the constitutional law and once that is recognized, the said right needs to be protected and it cannot succumb to the conception of class honour or group thinking which is conceived of on some notion that remotely does not have any legitimacy.”

Around this time, the Supreme Court decided a case that came to be commonly known as the Hadiya case [6]. In this case a 24-year-old lady converted to Islam and married a person of her choice. The Kerala High Court annulled the marriage on the ground of incongruities in her statements before the court, which led to the belief that the marriage was a sham. The Supreme Court also examined the lady in person and upheld the marriage when she admitted to it and also considering the fact that she was a major aged about 24 years. Notwithstanding this, the court permitted the National Investigating Agency (NIA) to continue investigations in respect of any matter of criminality. It appears that the NIA investigated several other inter-faith marriages and concluded that none of them involved any fraud or coercion, nor was there any evidence of a larger criminal design.

Unfortunately, the liberty granted by the court to the NIA coupled with a suggestion given in a case decided by the Uttarakhand High Court [7] prompted the Uttarakhand Legislative Assembly to enact the Freedom of Religion Act, 2018 whereby a marriage performed with the sole purpose of religious conversion could be declared null and void. [8] Interestingly, this law does not prohibit a live-in relationship or any other consensual arrangement.

Giving a back seat to freedom of choice, dignity and human rights, a stringent ordinance relating to marriage and forcible religious conversion has been passed in Uttar Pradesh. Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Haryana and Assam are contemplating a similar law. The purpose of these laws is to prohibit what is commonly called ‘love jihad’ which has no clear definition but is loosely described by one Chief Minister as jihadis playing “with the honour and dignity of sisters and daughters by hiding their real names and identities.” One Chief Minister went so far as to say that if such jihadis do not mend their ways, it will be the beginning of their journey to the grave. The possible death sentence that has already been pronounced is certainly not sanctioned by the Constitution or by law and can bring about a resurgence of mob lynching. The consequences of these statements are, therefore, very frightening. Are we as a society prepared for this and what happens to the law declared by the Supreme Court and the progressive interpretation of our Constitution? What happens to the freedom of choice? How about a war on child marriage which, by definition, is forced marriage? The carefully crafted dignity jurisprudence assiduously developed over the years by the Supreme Court is slowly being given an undignified cremation of the Hathras kind and might reach a point of no return if so-called anti love jihad laws are passed or extended to other communities.

Personal liberty in a crippled criminal justice system

Finally, on personal liberty: While dignity jurisprudence is on the way to the cremation ground, our criminal justice system is slowly drowning and taking the accused and victims of crime along with it. Tragically, neither of them sees the possibility of justice in the near future. Dignity and human rights have had a long struggle for recognition and now compassion and humanity in criminal law are becoming forgotten words.

The plight of undertrial prisoners has been spoken of and written about extensively, and does not bear repetition. But let us examine some recent instances where our criminal justice system has shown an absence of grace. There is a recorded instance of an 80-year-old in judicial custody for almost two years for allegations under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act or the UAPA. Recently, the Bombay High Court observed that he was virtually on his death bed, but he was still not given bail. I do not wish to delve into the merits of the allegations against him, except to note that he has been detained for being a sympathiser of terrorists. In July this year, he tested covid 19 positive and was even otherwise not in the pink of health, as one can imagine given his age, and yet the National Investigating Agency filed a 170-page affidavit opposing grant of bail. [9] Among other things, the Agency, unbelievably, alleged that he is taking “undue benefit” of the covid 19 pandemic and his old age for grant of bail. [10] More recently, after the Supreme Court virtually castigated High Courts across the country for giving little or no importance to personal liberty, this 80 year old, bed-ridden and on diapers was directed to be transferred to a super speciality private hospital. Even this was shamefully opposed by the NIA who insisted that he should be transferred to a government hospital otherwise a “wrong precedent” would be set. [11]

There is yet another strange case of an 82-year-old recently arrested under the UAPA suffering from Parkinson’s disease. In 1996, the Supreme Court had directed, in the case of DK Basu that any and every person who is arrested should be “subjected to medical examination by a trained doctor every 48 hours during his detention in custody by a doctor on the panel of approved doctors appointed by Director, Health Services of the concerned State or Union Territory. Director, Health Services should prepare such a panel for all Tehsils and Districts as well.” [12] This direction by the court might be difficult to strictly adhere to in these days of the pandemic and given that most prisons across the country are overcrowded. But surely, basic humanity requires that a super senior citizen must be medically examined at the time of arrest and fairly frequently while in judicial custody. I have no doubt that if a proper medical examination had been carried out, it would have been known that this 82-year-old prisoner did indeed suffer from Parkinson’s disease.

In any event, let us examine what transpired subsequently. Due to his disability, the super senior prisoner cannot hold a glass steadily and therefore requires a straw or a sipper for drinking water. Strangely, and I would say perversely, this was denied to him by the jail authorities. As a result, this super senior prisoner had to move the judiciary for a straw or a sipper for drinking water. How did the NIA react to his request? Believe it or not, the NIA sought 20 days’ time to file a reply to his request. How did the judiciary react to the extremely strange request of the NIA? Believe it or not, the judiciary accepted the request. Sorry, but in my opinion, this is bizarre, unacceptable and inhuman. How is this super senior citizen coping? Well, he is managing with the help of inmates and in his own words, “Despite all odds, humanity is bubbling in … prison”. Unfortunately, not in the heart and mind of the prosecution or the trial court.

Never mind that both the super senior citizens are accused of being sympathisers of terrorists. They are citizens of India also and we cannot treat our own people in such a disgraceful manner, regardless of their alleged crime. It is no wonder that instances of this nature are freely made use of by well-heeled economic offenders in foreign courts to challenge and stall their extradition to India.

Let me give you another example of how unreasonable the prosecution can be when it comes to dealing with under trial prisoners in our criminal justice system. Towards the end of February, there were riots in north east Delhi, apparently sparked by protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act. After extensive and intensive investigations, the police filed a charge sheet running into over 17,000 pages. The law, and plain and simple natural justice, require that an accused person must be given a copy of the charge sheet so that he or she knows the accusations made and prepare a defence. Well, in this case the prosecution indulged in a bit of sophistry and informed the Trial Court that the law does not differentiate between a soft copy and a hard copy and so the charge sheet can be provided to the accused on a pen drive, but not a hard copy. Why not a hard copy? No funds, says the prosecution! The Trial Court did not buy that argument and directed supply of a hard copy of the charge sheet to each accused person. Surprisingly, the prosecution found sufficient funds to challenge the order of the Trial Court and pay its lawyers, but while this debate will take its own time for being settled, the accused persons will remain in judicial custody holding a pen drive. The superior court, in this case the High Court, will certainly rule on the rights of the accused, but the real question is this: Should an undertrial prisoner be made to undergo this agony and spend scarce resources on engaging a lawyer for assertion of a right that has been recognized without demur in any and every criminal justice system and in a matter concerning personal liberty?

I request you to please try and visualize how unfair the entire process has become for the accused. There is nothing to show that all the accused are computer literate or have access to a functioning computer in jail or even outside jail. Indeed, there is nothing to show whether the accused are literate or semi-literate or even illiterate. To expect an undertrial prisoner, in such custodial circumstances, to prepare a viable defence is extraordinary and in violation of statutory and constitutional rights of an accused to a fair trial.

Finally, I would like to make reference to another rather strange case that throws light on the trials and tribulations of victims of State excesses. A journalist was on his way to Hathras to cover the story of the tragic rape and murder of a young lady and her cremation in the dead of night in the absence of knowledge or consent of her family. The journalist was preventively detained under Section 107 read with Section 151 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) on the apprehension that he is likely to commit a breach of the peace or disturb the public tranquillity or commit a cognizable offence. [13] Ordinarily, he should have been immediately released on executing a personal bond of good behaviour. That apart, the safeguards provided by Sections 111 and 116 were apparently not followed. The next day, the journalist was produced in court but was apparently not granted sufficient time to discuss his case with his lawyer, but remanded him to judicial custody in clear violation of a right of a citizen to have access to justice. On the third day, a First Information Report (FIR) was lodged in which it was alleged that the journalist had committed an offence, amongst others, of sedition and under the UAPA.

Around this time, a petition was filed in the Supreme Court by the union of working journalists for a writ of habeas corpus under Article 32 of the Constitution for his production and release from illegal detention. It is reported in The Hindu newspaper and a law-related website [14] that the Supreme Court was reluctant to entertain the writ petition, even though it was a matter relating to the personal liberty of an individual and the freedom of the press. Rather, it was observed by the learned judges that the illegal detention could well be challenged in the jurisdictional High Court. Liberty was given to the union to amend the petition and the proceedings adjourned for four weeks. A few days later, his lawyer again attempted to meet the journalist, but the Chief Judicial Magistrate disallowed the request and the jail authorities informed him that they were helpless without a court order. His lawyer has been quoted as saying, “I had gone to Mathura jail where [the journalist] is lodged, but I was not allowed to meet him. This is a violation of basic human rights and rule of law.” The order of the Chief Judicial Magistrate declining permission to the lawyer to meet the journalist is rather cryptic and reads: “No such order passed by Hon’ble S.C. No Power [of attorney] is annexed this application. Accordingly rejected.” First, an impossible situation is created by the Chief Judicial Magistrate and then that impossible situation is made use of by the jail authorities to deny access to justice.

The facts, as presented by the journalist’s lawyer, suggest that the complaint deserved looking into, and indeed the Supreme Court is looking into it, more particularly since the petition filed pertains to personal liberty and is under Article 32 of the Constitution. This article guarantees the right to move the Supreme Court by appropriate proceedings for the enforcement of fundamental rights conferred by Part III of the Constitution. The guaranteed right was invoked on behalf of the journalist to secure his personal liberty by pointing out that procedures known to criminal justice have, apparently, been flouted.

Dr. Ambedkar had said in the Constituent Assembly when Article 32 was under discussion as follows:

“Now, Sir, I am very glad that the majority of those who spoke on this article have realised the importance and the significance of this article. If I was asked to name any particular article in this Constitution as the most important – an article without which this Constitution would be a nullity – I could not refer to any other article except this one. It is the very soul of the Constitution and the very heart of it and I am glad that the House has realised its importance.”

As a fall out of these developments, in two different op eds in the Indian Express, one by a public intellectual and another by a senior lawyer strong words have been used for describing these developments and I needn’t say any more, except that I am reminded of what Mr Nani Palkhivala, a lawyer par excellence had to say, though in an entirely different context. In his book: We the Nation – The Lost Decades, he refers to an eminent writer saying that the court is no longer looked upon as a cathedral but as a casino.

Please assess the present-day situation and arrive at your own conclusion. On my part, I believe that in matters of personal liberty, we have travelled a long distance, but now seem to be going in reverse. Pious platitudes will not do – our courts need to walk the talk. Today, we need to reiterate and apply well established and settled principles of law that have always been universally applied. Many of the decisions that we had been relying upon as lawyers and judges seem to have been forgotten and a new jurisprudence is developing where issues of fundamental rights and personal liberty are on the back burner. If Babasaheb were alive today, he would recall WB Yeats and say: “I have spread my dreams under your feet; Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.”

In conclusion

Our founding fathers and mothers were far-sighted in matters of socio-economic justice, dignity of the individual and personal liberty. In interpreting socially beneficial laws, our judiciary cannot ignore the aspirations of the people and allow the Executive to call the shots. Otherwise, our democratic values will, like Humpty Dumpty have a great fall and no one will be able to put things together again. I believe that dissent and disagreement are slowly being turned into sedition; sedition is slowly being turned into an offence under the UAPA and an offence under the UAPA will soon be turned into a national security issue inviting the frightening prospect of an invocation of the draconian preventive detention law. In good time, human rights may well become human frights.

(Justice Madan B. Lokur is a Judge (Retired) of the Supreme Court of India. Article courtesy: Mainstream.)