Madan B. Lokur

I’d like to ask Bob Dylan a question for which the answer is not blowing in the wind: How many straws does it take to break a camel’s back?

This question arises in the context of the independence of the judiciary which has been tested over the last couple of years as never before, except during the Emergency. There has been debate and discussion with regard to administrative matters such as listing of cases and other serious issues such as the appointment and transfer of judges. By and large, the Supreme Court has left quite a few wondering what’s going on and quite a few making comments that are critical, bordering on the attribution of suspicion and accusations of bowing down to the wishes of those not necessarily supportive of an independent judiciary.

1. Sealed cover non-jurisprudence

We have seen three developments during this period, with each one of them requiring a rethink and each one giving rise to that suspicion.

First, we saw the emergence of what is now called ‘sealed cover jurisprudence’. In this, the court is handed over some papers in a sealed cover, the contents of which are not to be disclosed to anybody except the judges. This is recognised by the Evidence Act but it requires a procedure to be followed – an affidavit to be filed by the head of the concerned department claiming privilege. But, on a perusal of the documents, the claim of privilege can be upheld or overruled by the court. Theoretically (and only theoretically – since no one has seen these documents) a claim for privilege could have been upheld on the Rafale documents and could have been rejected on the detention report of children in Kashmir. Unfortunately, our judiciary has adopted an unacceptable practice of complete non-disclosure and the provisions of the Evidence Act have gone with the wind. On no occasion has the sealed cover procedure been adopted with a supporting affidavit claiming privilege.

Sure, the courts have called for documents in the past and have not disclosed the contents, as for example investigation reports. But this has been only to ensure that the investigation is proceeding in the right direction and is not influenced by extraneous factors or considerations. But on no occasion has the decision of the court been based on undisclosed documents. This has happened now, and is objectionable. For example, the final Juvenile Justice Committee report on the detention of children in Kashmir were not disclosed to the petitioners or their lawyers and the petition was disposed of by the court on their perusal. The right to know and the right to information are now passé – secrecy is the name of the game in which the state has been given the upper hand by the courts.

The secrecy has extended to important administrative issues as well. The report of an inquiry in a sexual harassment allegation against a former Chief Justice of India (CJI) is in a sealed cover and the contents of the report have not even been disclosed to the complainant. Should she not even know what the report says?

A follow up report by a retired judge of the Supreme Court on an alleged conspiracy has also been kept in a sealed cover and we will never know if there a conspiracy or not. Why is there so much secrecy in this? Is the court trying to hide something unpalatable? Maybe. The complainant was dismissed before the inquiry but reinstated with full back wages after the inquiry. This makes sense only if there was some truth in her allegations of sexual harassment.

On the conspiracy question, if there was a conspiracy, why is the court not acting against the conspirators? On the other hand, if there is no conspiracy, is there any harm in disclosing the conclusion and the reasons for the conclusion? How about taking action against the person who alleged a conspiracy in so serious a matter? The entire episode starting from the Saturday hearing presided over by the accused person himself now seems to be a charade. Perhaps one day, Deep Throat will tell us the truth.

While the Supreme Court keeps documents and information in a sealed cover close to its chest and bases its decision on it (as in the case of children detained in Kashmir), it has disapproved the high court for following suit. Information contained in a sealed cover was used by the Delhi high court to keep a former cabinet minister and present member of parliament in detention. The Supreme Court said:

“….. in present circumstance we were not very much inclined to open the sealed cover although the materials in sealed cover was received from the respondent. However, since the learned single judge of the high court had perused the documents in sealed cover and arrived at certain conclusion and since that order is under challenge, it had become imperative for us to also open the sealed cover and peruse the contents so as to satisfy ourselves to that extent. On perusal we have taken note that ……. Except for recording the same, we do not wish to advert to the documents any further since ultimately, these are allegations which would have to be established in the trial wherein the accused/co-accused would have the opportunity of putting forth their case, if any, and an ultimate conclusion would be reached. Hence in our opinion, the finding recorded by the learned judge of the high court based on the material in sealed cover is not justified.”

The Ayodhya judgment is a watershed for a different kind of secrecy. Perhaps for the first time, the specific author(s) of a judgment has not been disclosed. This is truly amazing. Of course, the judgment was unanimous, but then, why was there an addendum? Who authored the addendum? Only five people know the truth – the same number of people apocryphally believed to know the secret formula of Coca Cola.

A trend has been set and we have to wait and watch how far it goes.

2. Prioritising hearings

The Supreme Court also set an avoidable precedent in the hearing and prioritising of cases, particularly PILs.

The twin requirements that a PIL litigant must cross are: (i) show that she or he is a bona fide public interest petitioner and (ii) the cause canvassed is in public interest. It is for the court to take a decision on these threshold requirements. If the threshold is crossed on both counts, the court takes over the conduct of the case till its logical end – no conditions can, should, or are attached. Of course, if the court finds that even one of the requirements is not met, it will dismiss the petition.

The PIL petitioner usually assists the court, but even if she/he does not or creates a hurdle, the PIL petitioner can be replaced. This is precisely what transpired in a public interest petition filed by Sheela Barse who did not want to assist the court after a particular stage, but petitioned for permission to withdraw her PIL. The court did not grant her prayer, but substituted her with a legal aid body. Similarly and more recently, Harsh Mander was replaced by an amicus curiae when the court disallowed him from canvassing the cause of detenus in the detention centres in Assam, a cause in public interest. In other words, the public interest cause is more important than the petitioner.

Contrast this with the view expressed by the Supreme Court in a PIL pertaining to police atrocities against students protesting against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act. The court ‘declined’ to hear it till the violence stops. What was the basis on which the court concluded that the petitioners or the victims of police atrocities were responsible for the violence, or that they were powerful enough to stop it? Is it not possible to assume, conversely, that the violence would have been halted, by whoever was unleashing it, if the state had issued a statement that it will not implement the law for a few months? Perhaps that possibility was not considered and instead the citizens were put on the mat. Assuming the PIL petitioners were guilty of the violence, they could have been immediately substituted, following past precedent, by an amicus curiae and the hearing in the petition – that was clearly filed in public interest – could have proceeded.

Placing pre-conditions on hearing matters involving public interest is clearly inappropriate, particularly since most of such cases relate to issues concerning the depressed, underprivileged or disadvantaged sections of society. Again, the cause and not the person is important.

In this context, we have witnessed a ‘fresh’ definition of urgency in hearing a case. PILs relating to the detention of children and the preventive detention of adults in Kashmir under the dreaded Public Safety Act were not taken up with due despatch, as one would expect while dealing with a writ of habeas corpus. With so many judges in the Supreme Court, it is difficult to accept that it could not prioritise the hearing of the cases keeping the urgency of the situation in mind. The result is that even now, after more than seven months, some of these cases are pending in the Supreme Court and the high court. Personal liberty has taken a severe hit due to this. It is true that it is for the bench to accord priority to a case for hearing it, but according no priority to a case raising a constitutional issue is rather strange. What is the impact of this?

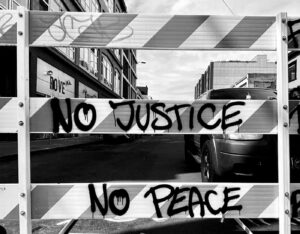

The absence of any urgency shown by the courts in hearing cases concerning human rights has emboldened the executive, who now know that when such issues are raised, they can take it easy and even keep a person in custody on trumped up charges at least for a couple of days, if not longer. A few days in custody, I believe, is enough to shake up an innocent person. And so, cases of non-existent sedition are filed for keeping persons in detention till she or he learns the lesson that it is better to keep shut. The sedition case filed against a teacher and the mother of an 11-year-old girl for staging a play in Karnataka is a classic example of high-handedness in restricting personal liberty and getting away with it. A report published in the Hindustan Times in February notes that a total of 156 cases of sedition were filed between 2016 and 2018. Between December 11, 2019 and mid-February this year, at least 194 sedition cases have been filed – with many ‘accused’ perhaps not being granted bail. Such cases instil fear, and the courts being sentinels on the qui vive must give confidence to the people that they are always available to protect their right to freely express their view, even if it is anti-establishment.

Less said the better about the ruthlessness shown by the police in Delhi, Uttar Pradesh and some other states like Telangana and Karnataka (to name a few) and the impunity with which they operate. They have left the courts virtually ‘speechless’ or have ‘compelled’ them to defer to the powerful.

A recent example – the government of UP put up hoardings in Lucknow displaying the photographs, names and addresses of alleged rioters who had participated in damaging public property, like burning buses. On a challenge to the hoardings through a PIL, the Allahabad high court directed their removal forthwith. Rather than comply with the order, the state government preferred a petition in the Supreme Court. The petition was treated as an urgent matter and taken up for hearing the very next day. Additionally, the (incorrect) precedent of not hearing a litigant till a condition is met was not followed. The state government could very well have been told that the court will not give it a hearing until the order of the high court is complied with. Impunity extends to giving scant regard to the orders of the courts – the Supreme Court did not stay the direction of the high court and yet the state government has not complied with it – that’s the respect for the court. But who will bell the cat?

3. Appointment of judges

The third unfortunate development is the successful flexing of muscles by the government in matters of transfer of judges and their appointment.

The ‘transfer’ of Justice Akil Kureshi from Madhya Pradesh, where he was recommended, for appointment as chief justice to Tripura is well known, though the reasons are not. Similarly, the ‘transfer’ of Justice Vikram Nath from Andhra Pradesh, where he was recommended for appointment as chief justice, to Gujarat is equally inexplicable.

Much has been written about the almost midnight transfer of Justice S. Muralidhar from the Delhi high court. Despite what anybody may say, it was anything but routine – nobody gets transferred at an unearthly hour and also without any ‘joining time’, least of all a constitutional authority. The Supreme Court has maintained a studied silence at this treatment, which by the way, has recently been repeated, making it perhaps a new normal.

The appointment of judges has been an equally tragic story. Recommendations are being processed at a snail’s pace – no urgency, despite huge arrears. At last count, more than 200 recommendations were pending at various stages and levels. Worse, some recommendations approved by the Supreme Court collegium have been returned for reconsideration by the government without adequate reason. Some of these recommendations have been reiterated by the collegium, but no warrant of appointment has yet been issued – the fate of these potential judges hangs on a weighted balance. To make matters worse, there is at least one recommendation that has twice been reiterated, but not yet acted upon – with the courts doing nothing about it.

So, chief justice recommendees have been at the receiving end as well as judges and potential judges. Judges recommended for appointment to the Supreme Court have been at the receiving end, with a long wait for appointment. Two well-known instances are of Justice K.M. Joseph and Justice Indu Malhotra. Where will this stop?

These and similar instances have led to the feeling among many that over the last couple of years, the court has been ‘executivised’. This is a polite suggestion that the independence of the judiciary is in danger, through self-inflicted wounds and some inflicted by the executive. And now suddenly comes the news that a recently retired CJI has been nominated to the Rajya Sabha by the president on the aid and advice of the council of ministers. How does the acceptance of the nomination impact on the independence of the judiciary? What is the message sent out, keeping in mind the events of the last couple years?

From Supreme Court to Rajya Sabha

For a CJI whose tenure was marred by and mired in controversies of all three categories mentioned above and whose tenure strengthened the perception (beginning with the tenure of his predecessor) that the judiciary could not take on the government on crucial issues, it was unwise to have accepted the offer. It is well known that the judiciary is the weakest of the three pillars of democracy for it neither has influence over the sword or the purse. How then does it have its decisions and directions enforced – both judicial as well as administrative? If the judiciary commands moral authority, and has the trust and confidence of the people, then the power and strength generated by that perception is enough to pressure the executive to obey the orders and directions of the court.

By accepting an offer not commensurate with the dignity of the office held a few months earlier, the former CJI has led many to believe that he has been rewarded by the government, the biggest litigant, for doing their bidding when it mattered. This may or may not be true, but that is the perception.

It may also not be a quid pro quo (as some would have it) or a favour for favour for some decisions (not necessarily judgments). It could well be for staving off embarrassment in an administrative or judicial issue or playing ball through silence or failure to put one’s foot down on an administrative issue or appointment or transfer of a judge(s) – who knows? His acceptance of the nomination, and the criticism this has naturally generated, has considerably diminished the moral stature of the judiciary and thereby collaterally impacted on its independence. Public perception is important and it has been rendered totally irrelevant, thereby taking away one of the strengths of the judiciary.

Whataboutery does not redeem the situation. No one has publicly applauded the earlier election to the Rajya Sabha of Justice Ranganath Misra or Justice Baharul Islam or the appointment of Justice Sathasivam as the governor of Kerala in 2014. How then can anyone make use of these precedents to justify the nomination of the recently retired CJI to the Rajya Sabha? If the precedents were wrong, the present nomination is wrong; if the precedents are acceptable, there is nothing to be disillusioned with the present nomination – and the independence of the judiciary be damned.

So Bob, any answers?