Subodh Varma

According to various estimates, Jharkhand has 40% of the country’s mineral resources. It has 27.3 per cent of India’s coal reserves, 26 per cent of iron ore, 18.5 per cent copper ore, besides having deposits of uranium, mica, bauxite, granite, limestone, silver, graphite, magnetite and dolomite. It also has large quantities of stone, limestone and sand. Almost 20% of the state’s revenue arises from mining activities.

But despite this abundance, and despite mining having started as far back as the first decade of the 20th century, Jharkhand continues to be one of the poorest states in the country ranking low on various economic and social indicators. It was thought that after the state was carved out of Bihar in 2000, development will take place. But that also doesn’t seem to have happened. Why?

Disastrous Model

The main reason for this is that mineral resources were seen by the political rulers as something that has to be appropriated, or rather seized, and sold off. The people living on those lands were mostly seen as encumbrances—obstacles that had to be duped or coerced into giving way for big mining companies. Thus mining became an activity that was hostile to the people. They were evicted, turned into serfs, forced to migrate, or survive in inhuman conditions. This naturally led to resistance to mining and all the problems that follow.

Besides this, the other major fault in policy lay in handing over mines to private entities. The contradiction with people intensified as 3,963 lessees and 6,647 dealers took over mining and trading operations in the state. These were unscrupulous operators with only one objective—to make profit, come what may. As a result, the distance between mineral resources and people became even greater and the relations even more fraught.

Some may argue that the state government does earn royalties and fees from leasing out the mines, so what is wrong with this model? The answer is very simple: the state government (this one and previous ones) has fixed the game in such a way that only a small amount of royalties and other fees finally accrue to it, leaving the operators with huge profits. As it is, royalty rates are low and mostly levied on pit mouth prices or even cost of production prices for captive mines. Even the CAG has castigated the Jharkhand state government for non- or short levy of royalties by applying incorrect rates, under-estimating production, not penalising late payments etc.

As a result, the richest mineral state is earning a paltry sum from various fees it charges from companies that are exploiting the minerals and selling them off for big profits. According to the latest Budget presented by the BJP ministry that rules Jharkhand, in 2018–19, Rs 6,783 crore was the revenue (revised estimate) accruing to the Mines Department from various fees and rents. In 2019–20, the Budget hoped to collect Rs 8,042 crore. In addition, sand extraction yielded revenue of Rs 299 crore in 2018–19 and was expected to yield Rs 362 crore in the current year.

These are paltry sums, nowhere near the actual final sale value of minerals that are being relentlessly extracted from the land in Jharkhand. Partly, they reflect the clout of mining industrialists who keep such rates low by pressurising the government. But partly they also result from the rather low level of mineral extraction because of not taking the people in confidence and hence facing resistance to mining.

District Mineral Fund Sham

In 2016, the Modi government announced that in order to plough back some of the profits that mining activities generate, the mining operators will have to pay 10% of the royalties to a trust set up in each district. It was called the District Minerals Foundation (DMF). The funds thus collected would be used for such development work like providing piped water supply to communities, building roads and toilets, and so on.

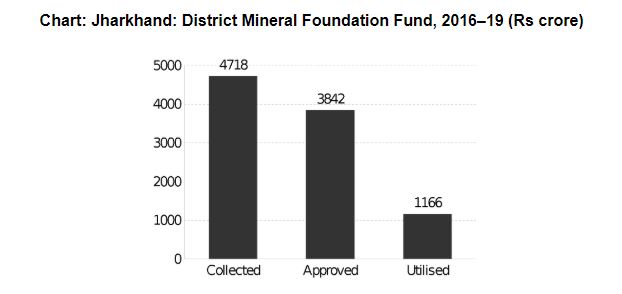

The chart reveals the fate of this program—called Pradhan Mantri Khanij Kshetra Kalyan Yojana or PM Mining Sector Welfare Programme. Remember, the state has been ruled by BJP since 2014, so there is complete political convergence with the BJP led central government in Delhi. No questions of any dissonance. As you can see, just 24% of the funds thus collected have been used for the ‘developmental work’.

Clearly, the whole thing has turned into a macabre joke. It seems all the projects sanctioned till date in Jharkhand—some 25,000 odd—are still in progress! In three years not a single one has been completed.

Meanwhile the state’s inhabitants continue to get ground down in abject poverty, face joblessness and the state has reported some of the most shocking numbers in terms of malnutrition, even starvation deaths. The coming elections may see the BJP state government dislodged, going by the widespread discontent, but a deeper relook is necessary at the mining and mineral policy if the people are ever to get the benefit of these resources.

(Subodh Varma is a senior journalist.)