Today, November 14, is the birth anniversary of former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

On November 11, Prime Minister Narendra Modi tweeted: “I pay homage to Acharya JB Kripalani on his birth anniversary. He is widely respected as a true beacon of India’s fight against colonialism. His tireless work to strengthen democracy and social equality has etched a permanent mark on our nation’s fabric. His life and work was always about upholding the values of liberty and justice.”

One cannot help but marvel at the prime minister’s capacity to publicly praise historical personalities whose values stood in direct opposition to his own. Of course, it is also entirely possible that his lavish praise for Kripalani was a sly dig at Nehru, with whom, it is well known, Kripalani did not enjoy an easy equation.

Jeevatram Bhagwandas Kripalani – called ‘Acharya’ because he was once the principal of Gujarat Vidyapith in Ahmedabad – worked closely with Gandhi during the Champaran Satyagraha, Dandi March and the Quit India movement. He not only went on to become the president of the Indian National Congress at the crucial time of Independence, but also a member of the Constituent Assembly, and a subsequent four-time MP.

J.B. Kripalani also happened to be a distant cousin and close friend of my own nana (maternal grandfather). The two grew up in Hyderabad, Sindh, on the same lane, Kripalani ‘ghitti’ as it was called. After my grandfather moved to Kolkata in 1918, Acharya made it a point to come and stay with him whenever he visited the city.

Always dressed in a white, khadi dhoti-kurta, Acharya was fun to be around. He loved to play chaupar, an ancient cross and circle board game, with my grandfather. Politicians of various persuasions would come home to nana’s house on Chowringhee Lane to meet Acharya who, while not stopping his game on their account, would nonetheless carry on conversations with them. He would, however, swear loudly at the dice each time they failed to deliver the desired 1 plus 12, or another magic figure.

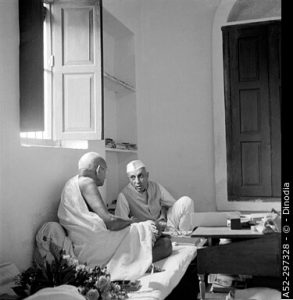

Kripalani made no secret of the fact that he and Nehru did not see eye to eye on many issues, the main ones being the division of power between the Congress party and the elected government, and the debate over a rural-centric economy versus an urban-centric one.

Following India’s defeat in the Indo-China war of 1962, he moved an unsuccessful no-confidence motion against Nehru. Of that particular session of parliament, Mahatma Gandhi’s grandson Gopalkrishna Gandhi wrote:

“Kripalani brought into the House a large bundle of telegrams from different parts of India in support. They poured down from his quivering hands as he moved his resolution charging Nehru with authoritarianism. Nehru sat through and heard the excoriation with a smile, not of condescension but of respect for the veteran and his veteran right.”

And yet, it is worth noting, that at no point in his political career did his opposition to Nehru ever turn into personal, ad hominem attacks. Nor did he bad mouth Nehru to my grandfather or to the rest of us. It is also worth remembering that Nehru’s response to Kripalani’s unrelenting criticisms remained dignified no matter how heated their debates and arguments became, both within the and outside the parliament.

For example, not only did Nehru back Kripalani’s bid for the Congress presidency against conservative Purushottam Das Tandon in 1950, he even offered Kripalani a place in the Union cabinet as well as a governorship. But Kripalani, very much his own man, turned down both offers and went on to eventually become an independent MP.

As a courtesy, Nehru also left Kripalani’s constituency uncontested by the Congress, till Kripalani insisted on a fight and ended up losing the North Bombay Lok Sabha election seat in 1962 to Krishna Menon. (Kripalani, incidentally, was given a front seat by the Lok Sabha Speaker in parliament as a mark of respect, even though independent MPs are not given this privilege.)

It is also interesting to note that when the Blitz weekly called Kripalani “cripple-loony”, the Lok Sabha admonished its Chief Editor, Russi Karanjia for “denigrating and defaming a member of parliament.” This, despite Karanjia’s closeness to Nehru. A far cry, indeed, from the current government that uses both print and electronic media to punish dissenters and political opponents.

When Nehru passed away in 1964, Kripalani wrote an article “After Nehru” in the July edition of The Economic Weekly that year:

“India was almost the only colonial country which had given a determined fight to British imperialism and in the process made conspicuous sacrifices. Its leaders trained under Gandhiji had fully imbibed the best British traditions of humanism, liberalism and democracy… these well-established traditions were kept up by Jawaharlal.”

Nehru and Kripalani’s contentious and prickly, yet ultimately respectful relationship, underlines one of the great lacunae of current Indian parliamentary democracy – the ability to debate without denigrating, and criticise without stooping to use the kind of language that someone like Bharatiya Janata Party MP Ramesh Bidhuri, for example, has gotten away with.

Our Prime Minister is good at paying verbal homage to the departed greats on social media. It is perhaps too much to expect much else from him. Let us hope that the next Lok Sabha will see those who, like Nehru and Kripalani, can actually revive our great democratic traditions of discussion, debate, and dissent, and do justice to them.

(Rohit Kumar is an educator, author, and independent journalist. Courtesy: The Wire.)