[The following text is Aditya Mukherjee’s presidential address at the 82nd session of Indian History Congress (IHC), conducted from December 28-30, 2023, at Kakatiya University, in Warangal, Telangana. Mukherjee, who was earlier with the Jawaharlal Nehru University, in his presidential address, spoke about the IHC’s role in the promotion of scientific, secular and anti-imperialist history over the past 85 years. This is the first part of a long speech. The subsequent parts will be carried in the coming issues of Janata Weekly.]

●●●

Friends,

I am thankful to the Executive Council of the Indian History Congress for electing me as the General President this year. I am deeply honoured to be presiding over this august body, the largest and most representative organisation of historians in India which was created during the heyday of the Indian national movement in the mid nineteen thirties. In conformity with the values of our national liberation struggle, symbolised as the “Idea of India”, the Indian History Congress has spearheaded the promotion of scientific, secular and anti-imperialist history for over 85 years.

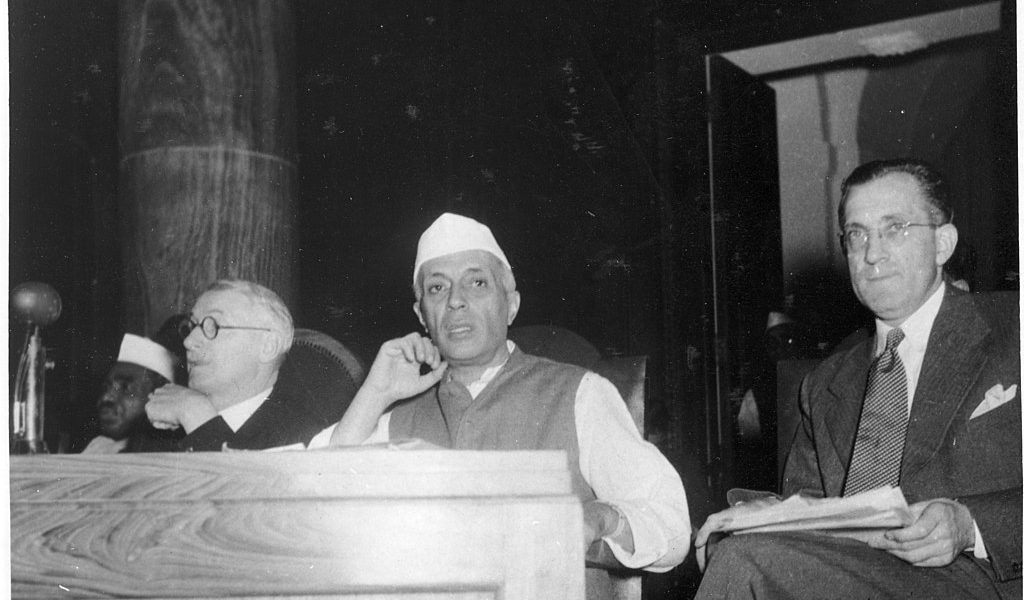

As all of you are aware, the Idea of India is deeply threatened today and the discipline of history is being mauled beyond recognition and weaponized to destroy the Idea of India by religious communal forces[1], which not only did not participate in India’s freedom struggle but indeed collaborated with imperialism. It is perhaps appropriate that on his 60th death anniversary I should focus my address on what we can learn from Jawaharlal Nehru, among the foremost champions of the Idea of India, as well as of a scientific and meaningful history. I believe much can be learnt from him to explain our present and chart out a vision of the future.

It is because of what Nehru stood for that he is demonized so blatantly by the communal forces today. All kinds of lies and abuse are spread about him using the massive propaganda machinery that the communal forces command today. Nehru is blamed for all of India’s problems, from the partition of the country, the Pakistan problem, the China problem, the crisis in Indian agriculture, the Kashmir issue, crisis in the educational system, the persistence of poverty, the growing religious polarisation in recent years, amending the constitution to curb democracy, to almost any problem facing the country today. This, nearly 60 years after his passing away! A website called Dismantling Nehru with the subtitle ‘The last Viceroy of India’ is on social media repeating a canard spread by the RSS since independence, which they thought was a black day, refusing to unfurl the national flag. A book called 97 Major Blunders of Nehru has now been expanded to Nehru Files: Nehru’s 127 Historic Blunders (Nehru Ki 127 Aitihasik Galtiyan). The list keeps growing as new ‘facts’ are invented. He is even said to have a secret Muslim ancestry. Such is the hatred spread about him that one BJP leader, as reported in an RSS journal, went to the extent of saying that Nathuram Godse should have aimed his gun at Nehru.[2] Apart from spreading lies about him, the effort is to also erase his memory from the minds of the Indian people. The iconic Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) built on the premises where he lived as the first Prime Minister of India is no more. Nehru has been dwarfed in that space which now houses a massive museum to all Prime Ministers (a global first!) and is called the Prime Ministers’ Museum and Library. In Rajasthan, it was reported that textbooks for school children were created during the BJP regime in which “there is no mention of Nehru either in the chapter (on) Freedom Movement or in India After Independence.”[3] The Indian Council for Historical Research (ICHR), not to be left behind in pushing the BJP government initiative, recently put up a poster celebrating the 75th Year of Indian independence where the pictures of many freedom fighters were put up but Jawaharlal Nehru was absent and V.D. Savarkar was added,[4] a person who apologized to the British, promising total loyalty, and after his release cooperated with the British Government when the people of India were sacrificing their lives in the Quit India movement and Jawaharlal Nehru spent nearly three years in jail in Ahmednagar Fort with Maulana Azad, Sardar Patel and other Congress leaders.

Not even the British, who were the chief ally of the communal forces, demonize Nehru in this manner, and this despite Nehru spending 30 years of his life fighting the British, nine of those years spent in British jails.[5] Though there has been a resurgence of the neo-colonial critique of Nehru by people like Tirthankar Roy, Meghnad Desai, etc., it is not as crass and vulgar as that done by communalists.

Nehru and the Discipline of History

The demonizing of Nehru and the values he stood for could only be done by distorting history and that is what the communal forces have done blatantly. As I am addressing a distinguished gathering of historians, I would like to begin with a brief discussion on Nehru’s own attitude to the discipline of history before moving on to a discussion of how Nehru is being wrongly demonized by detailing some of his actual historic contributions to the making of modern India. I do so as I believe that Nehru, from as early as the 1930s, provided a framework, partly demonstrated in his own historical writings, that was in sharp contrast to the colonial and communal framework. Some of the most distinguished scholars of the country adopted and developed decades later, the Nehruvian framework. Much can be learnt from Nehru in this sphere even today.

While referring to Nehru’s outstanding historical works, Glimpses of World History, Autobiography and The Discovery of India, all written in British jails between 1930 and 1944, Professor Irfan Habib made a very significant comparison with Gramsci’s iconic Prison Notebooks:

“These prison works invite comparison in both quantity and quality with the kind of writing that Antonio Gramsci produced as a communist prisoner in fascist Italy. There are true similarities in that both … went to history to find answers to the questions raised in their minds as men of action”.[6]

As Nehru himself said “Because fate and circumstances placed me in a position to be an actor in the saga, or the drama of India, if you like, in the last twenty or thirty years in common with many others, my interest in history became not an academic interest in things of the past … but an intense personal interest. I wanted to understand those events in relation to today and understand today in relation to what had been, and try to peep into the future…. one has to go back to (history) to understand the present and to try to understand what the future ought to be”.[7] Irfan Habib quoted Marx’s famous statement, “the philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways, the point is to change it”, to argue that for a ‘man of action’ like Nehru, history was not just a directionless descriptive narrative placed in a chronological order but a resource from which one sought to understand the present in order to try to shape the future.[8]

Nehru urged historians to approach history in this manner. For example, just when India was emerging from the holocaust like situation caused by communal strife and the partition of the country on that basis, and the newly born Indian state was to embark on the path of building a secular, inclusive country, Nehru tells historians in December 1948: “History shows us both the binding process and the disruptive process… today a little more obviously – the binding or the constructive forces are at work, as also the disruptive or the fissiparous forces, and in any activity that we are indulging in we have the choice of laying emphasis on the binding and constructive aspect or the other”. While exhorting the historians to emphasise the former he warns, true to the rigours of the discipline of history, “We must not, of course, give way to wishful thinking and emphasize something which we want to emphasize… which has no relation to fact. However, he goes on to say, “Nevertheless, I think it is possible within the terms of scholarship and precision and truth to emphasize the binding and constructive aspect rather than the other, and I hope the activities of historians … will be directed to that end”.[9]

This is what Nehru himself did brilliantly in his classic work The Discovery of India, while the colonial/communal approach was to constantly try to weaponize any conflict in the past to exacerbate them in the present.

The colonial/communal interpretation repeatedly emphasized the ‘trauma’ experienced as a result of Hindu–Muslim conflict. These theories of trauma were often created centuries after the so-called traumatic events. A case in point is the alleged trauma felt by ‘Hindus’ because of the destruction of the Somanatha temple by a ‘Muslim’ invader, Mahmud, the Sultan of Ghazni (now in Afghanistan) more than a thousand years ago in 1026. After independence, a demand was made that a grand temple be constructed at Somanatha. K.M. Munshi claimed in 1951, “… for a thousand years Mahmud’s destruction of the shrine has been burnt into the collective sub-conscious of the [Hindu] Race as an unforgettable national disaster.” In fact, there was no evidence of a thousand-year old trauma. Munshi, perhaps unknowingly, was reflecting the colonial perspective created in the 19th century. Because the earliest mention discovered so far of ‘Hindu Trauma’ caused by this ‘Muslim’ invasion in 1026, which had to be avenged, is nearly 800 years later, in 1843 when the issue is brought up in the British House of Commons. Colonial historiography since the 19th century has used such events to evolve a notion of permanent confrontation between the Hindus and Muslims, laying the basis of the ‘two nation’ theory, which argued that Hindus and Muslims constituted two distinct nations. The communalist picked up this theme and amplified it. The eminent historian Romila Thapar, using a multiplicity of sources, has convincingly demonstrated that no such permanent confrontation between Hindus and Muslims occurred historically as a result of the destruction of the Somanatha temple. 150 years after its destruction a Hindu king rebuilt the Somanatha temple without even a mention of Mahmud having destroyed it. 250 years later land was given to a Muslim trader to build a mosque on land belonging to the same temple’s estates with the approval of the local Hindu ruler, local merchants and priests! No signs of a ‘trauma’ in the ‘collective memory’ of Hindus is visible until it was a ‘memory’ constructed much later under colonial patronage by their allies, the religious communal forces.[10] Destruction of religious places was routinely done across religions and sects often to loot the wealth of these institutions or establish authority in ancient and medieval times and was perhaps treated as such. Nehru himself had a much more nuanced account of Mahmud Ghazni than that portrayed by the colonial/communal combine, where he sees him as “far more a warrior than man of faith” who used his army raised in India under a Hindu general named Tilak, “against his own co-religionists in Central Asia”.[11]

The nationalist intelligentsia in the colonial period put forward a totally different interpretation of Indian history from the colonial/communal one, where they were not trying to create memories of historical ‘trauma’ in order to create differences in the present. On the contrary they drew on the reality of Indian society and how it organically dealt with religious, caste and other difference through birth of new religions like Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism or movements spanning many centuries like the Sufi and Bhakti movements. Jawaharlal Nehru perhaps best argued this position in his magisterial magnum opus, The Discovery of India, written from prison in the 1940s. The lessons that Nehru tried to draw from Indian history were connected to his imagining India’s future as a modern democratic country based on enlightenment values, ‘the Idea of India’. He focused on a critical aspect of India’s civilizational history; an openness to reason and rationality, a questioning mind and acceptance of multiple claims to truth, a dialogical tradition of being in conversation and discussion with each other, the ability to live with difference, accommodate, adjust, resolve and transform rather than violently crush difference.[12] Nehru draws from the Indus valley civilisation, the Rig Veda, the Upanishads, the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, the Gita, Buddha, Aśoka, Alauddin Khilji, Amir Khusrau, Akbar, Vivekananda to Gandhi to illustrate the above. He also emphasized how the shared traditions in language, music, poetry, painting, architecture, philosophy and everyday practice cutting across religion and caste contributed to the creation of a composite culture. While talking of songs composed by Amir Khusrau he said, “I do not know if there is any other instance anywhere of songs written 600 years ago (in the ordinary spoken dialect of Hindi) maintaining their popularity and their mass appeal and being still sung without any change of words”.[13] He talked of the emergence of the Indian civilization that occurred over the centuries through the ‘absorption’, ‘assimilation’ and ‘synthesis’ of all the influences India was exposed to through trade, invasions, migration and inter mixing. From the Indus Valley civilization five thousand years ago to the Dravidian, Aryan-Central Asian, Iranian, Greek, Parthian, Bactrian, Scythian, Hun, Arab, Turk, early Christian, Jewish, Zoroastrian, Afghan, Mughal, etc., all leaving their mark “like some ancient palimpsest on which layer upon layer of thought and reverie had been inscribed, and yet no succeeding layer had completely hidden or erased what had been written previously”.[14]

It is to this organic process through which the Indian people had learnt to negotiate differences of multiple religions, languages, caste etc., that colonialism came as a shock. It is as if Indian history ‘ceased’, to use a phrase used by the African revolutionary, Amilcar Cabral, for the period of colonial rule lasting nearly 200 years. Colonialism not only stopped the dynamic process of negotiating differences but actually froze or even accentuated these differences. And the communal forces were the chief instruments in their hands for accomplishing this task. The world has learnt at a very heavy cost, from Ireland, the oldest colony, to recent events in Palestine (about the Imperialist role in which Nehru has much to say) and the experience of large parts of Asia and Africa, including India, that the longest lasting legacy of colonialism has been that it left behind a divided people.

One method used by the colonial/communal forces to create a religious divide, of which Nehru was very critical, was the colonial periodisation of Indian history, done by James Mill in the early 19th Century, “into three major periods: Ancient or Hindu, Muslim and the British period”. He thought “it is unscientific to divide history like this” and said, “This division is neither intelligent nor correct; it is deceptive and gives a wrong perspective. It deals more with the superficial changes at the top than with the essential changes in the political, economic and cultural development of the Indian people”.[15] He said, “It is wrong and misleading to talk of a Muslim invasion of India or of the Muslim period in India, just as it would be wrong to refer to the coming of the British to India as a Christian invasion, or to call the British period in India a Christian period”.[16] He questioned the defining of a period by just the religion of the ruler and emphasized the wider social and economic and cultural factors which defined a period and also pointed out the continuities and cultural intermixing of people belonging to different religious faiths. Later historians have confirmed Nehru’s position while critiquing the colonial/communal periodization of Indian history.[17]

In fact, Nehru was extremely critical of looking at history with “the old and completely out-of-date approach of a record of doings of kings and battles and the like”. He said, “the whole conception of the history of a country being the names of a large number of kings and emperors and our learning them by heart, I suppose, is long dead. I am not quite sure whether in the schools and colleges of India it has ceased to exist or not, but I hope at any rate that it is dead, because anything more futile than children’s study of the record of kings’ regions and battles I cannot imagine”.[18]

On the contrary Nehru, anticipating what has now globally become an accepted norm in cutting edge historiography, emphasized “the social aspect of history”. The need for “much closer research into the daily lives of the common man. Maybe in family budgets a hundred or a thousand years ago…which make us realize something of what the life of humanity was in the past age”. As he put it in his characteristically beautiful prose, “It is only then that we really clothe the dry bones of history with life, flesh and blood”.[19]

Nehru was deeply aware of the various biases in history writing and very critical of the Eurocentric and colonial approaches which often overlapped, and which unfortunately exercise considerable influence including in the former colonies till today.[20] Giving his inaugural address to the Asian History Congress, Nehru said: “the immediate object of the History Congress should be to straighten out all the twists which Asian history has received at the hand of the Europeans. While some of them are very fine historians, their approach has nevertheless been based on Europe being the centre of the world”.[21] He continued, “In the case of India, a Western scholar, especially from the United Kingdom, inevitably tended to look at the history of India as if the past few thousand years were a kind of a preparation for the coming British dominion in India”. However, Nehru warned that “as a reaction to that sometimes our own historians have gone too far…. There is the nationalist history which, starting from a strong nationalist bias, praises everything that is national at the expense of other things”.[22] As early as the 1930s, reacting to the nationalist tendency to imagine a ‘Golden age’ in the past which the communalists used to create a religious divide, a tendency that has become rampant today, he said: “Everywhere are to be found people who consider their own country the best, and regard it as sacred soil. They only study their ancient history and award it a high place – it becomes Satyayug or Ramrajya; and the hope remains that the same may be restored”.[23] He argued, “Both these approaches…the nationalist approach and imperialist approach distort history. They sometimes suppress history”.[24] Nehru showed in his own writing in the Glimpses of World History and Discovery of India how one could be firmly anti-imperialist and also have pride in one’s own history — – for the genuine achievements without resorting to blind imaginary glorification of one’s past overlooking all the warts and blemishes.

While on the subject of Eurocentric/colonial positions, Nehru very early on refutes the tendency to obfuscate the difference between the empires of the Ancient and medieval period and the modern colonial empires emerging with the rise of capitalism. A tendency which has continued till today.[25] He says as early as 1933, “… There have been vast empires for thousands of years, but modern imperialism is a new concept developed for the first time in recent years…. But very few of us have understood its real import and often mistake it for imperialism of the old. Unless we understand this new imperialism properly and discern its roots and branches, we cannot grasp the conditions of the present-day world and cannot properly wage our battle for freedom”.[26] In fact, throughout the pages of the voluminous Glimpses of World History, Nehru maintains and highlights this clear distinction and explores the very complex evolution of modern imperialism.

Nehru repeatedly questions the colonial characterisation, picked up by the communalists, of the medieval period when many of the rulers in India were Muslims, as ‘foreign rule’, clearly distinguishing it from British colonial rule, which he described as foreign rule. Lest one thinks it is stating the obvious one may point out that our current Prime Minister repeatedly, from the ramparts of the Red Fort in his Independence Day speech, his speech in Parliament as Prime Minister in 2014, his address to the US Congress in 2023, etc., has reiterated the RSS position and talked of 1000 years of foreign rule (sometimes he makes it 1200, presumably 200 years is of little relevance in a long history). With one stroke all Muslims rulers were declared as foreigners from whose alleged loot and “slavery” India had to win independence![27] The paradox is that the forces which did not play a part in the actual struggle for freedom against British colonial rule, except to weaken the national movement against it, talked of freedom from a so called ‘Muslim’ rule in the medieval period! Nehru, while critiquing the ‘Hindu, Muslim and British period’ characterisation (discussed above) commented on this aspect, distinguishing the medieval period, when many rulers were Muslim in India, from the British period which is what he saw as a period of foreign rule. He said:

“The so-called (Hindu) ancient period is vast and full of change, of growth and decay, and then growth again. What is called the Muslim or medieval period brought another change, and an important one, and yet it was more or less confined to the top and did not vitally affect the essential continuity of Indian life. The invaders who came to India from the north-west, like so many of their predecessors in more ancient times, became absorbed into India and part of her life. Their dynasties became Indian dynasties and there was a great deal of racial fusion by intermarriage. A deliberate effort was made, apart from a few exceptions, not to interfere with the ways and customs of the people. They looked to India as their home country and had no other affiliations. India continued to be an independent country.

“The coming of the British made a vital difference and the old system was uprooted in many ways. They brought an entirely different impulse from the west, which had slowly developed in Europe…and was taking shape in the beginnings of the industrial revolution. The British remained outsiders, aliens and misfits in India, and made no attempt to be otherwise. Above all, for the first time in India’s history, her political control was exercised from outside and her economy was centred in a distant place. They made India a typical colony of the modern age, a subject country for the first time in her long history”.[28]

A few more points on Nehru and history writing which are relevant to us even today.

From very early on, Nehru was a votary of looking at history in a global context and was an exponent of what is now fashionably called ‘connected histories.’ He said, “The old idea of writing a history of any one country has become progressively out of date. It is impossible today to think of the history of a country isolated from the rest of the world. The world is getting integrated. We have … to consider history today in a world perspective”.[29] Globally, “events are all closely inter-related. One event affects the other and if all the developments of world history are taken together then some sort of laws and causes emerge and we can understand the course and significance of world history. By knowing this some light is thrown on all events of world history and we can see our course ahead”.[30] Further he said “It is quite impossible today to think of current events or of history in the making in terms of any one nation or country or patch of territory; you have inevitably to think of the world as whole”.[31]

As a ‘man of action’, one who contributed significantly to the making of history Nehru saw the need to keep the big picture in mind while approaching history. He said “It has been given to us in the present age to play a part in the making of history and for a person who does that it becomes an even more important thing to understand the process of history so that he might not lose himself in trivial details and forget the main sweep”. He urged the historians too not to get lost in the details, so that they may “see the wood a little more and not be lost in the individual tree”. He added, “any subject that you may investigate” should “be viewed in relation to a larger whole. Otherwise, it has no real meaning except as some odd incident which might interest you”.[32]

Again, as a man of action, Nehru urged “historians…that they should not always write only for their brother historians…. for the charmed circle of people who are interested in a specifically narrow aspect” which “loses all interest for the wider public”. They should “try to appeal to the minds of the larger public—the intelligent or semi-intelligent public”. He did not believe “popularization …means a deviation from scholarship. I do not think there is any necessary conflict between real scholarship and a popular approach”.[33] He had as early as 1933 urged, “books should be written not for a few scholarly persons but should be such that a person with very limited reading–a farmer or a labourer even—should be able to understand it. Unless the masses understand it, our labour would be in vain”.[34] Some of the tallest scholars in India inspired by the Nehruvian dream did try to do what he desired, writing school-texts, popular pamphlets and books,[35] while others, often in the name of the poor and the subalterns, went into a post-modernist discourse which at least I, even after more than four decades of trying to understand the discipline of history, have great difficulty even in beginning to decipher.

Finally, a comment on how Nehru saw his role in taking the historical process forward.

The lessons he learnt from Indian history of the acceptance of the existence of multiple truths, of a non-violent dialogical tradition, of negotiations of truth claims and conflict and arriving at a higher level of synthesis, were greatly strengthened by his increasingly deeper understanding of Gandhiji and his practice. This involved a change in his own Marxist understanding which he had argued till the mid 1930s, as seen in the Autobiography, towards a more complex Gramscian Marxist understanding of how social change was to be negotiated.[36] His more mature understanding was reflected in The Discovery. This shift has often been seen as Nehru’s contradictory and vacillating nature, his total dependence and subservience to Gandhiji, his giving in to vested interests etc.[37]

In an insightful work, Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee sees Nehru’s doubts, his ambivalence, openness and engagement with apparently contradictory positions not as his weakness or vacillating nature but as his strength. He is correctly critical of people like Partha Chatterjee who dismiss Nehru’s absolutely outstanding work, The Discovery of India, as a book of ‘rambling, bristling with the most obvious contradictions’.[38] (Other scholars such as the Eurocentric Marxist, Perry Anderson also shockingly rubbish Nehru’s Discovery calling it “a steam bath of Schwärmereii (over enthusiastic and sentimental)” with a “Barbara Cartland Streak”!)[39]

As Bhattacharjee argues in elegant prose:

“The idea of liberty needs to be reconciled with the presence of contradictions. No idea or truth-claim can justify the sacrifice of human lives. It would mean the barbarism of truth. Ethics provokes us to think of freedom without violence.

“Nehru did not sit on horseback with sword in hand, and rush towards the windmills of history thinking they were giants he had to exterminate. He did not hallucinate from the desire to rid the world of all its ills and create a gigantic prison in the name of paradise”.[40]

This is where Nehru learnt from Gandhiji. He accepted Gandhiji’s position that however good the end the means had to be ethical and non violent.[41] For Gandhiji, his deep conviction on non-violence did not emerge from the fact that it was a brilliant tactic to fight the British, which of course it was, but from his philosophical position that nobody could make the claim of having arrived at ‘transcendental truth’ or absolute truth. His belief in the possibility of multiple truths and multiple paths to the seeking of truth would not allow for violence against anyone. The Enlightenment project emerging from Europe often faltered on this ground, where the notion of possessing the ultimate truth justified mass killings by revolutionary movements (in the name of democracy and the people) thus negating a critical aspect of democracy, every human being’s right to differ. Gandhiji saw this weakness in the French and the Russian Revolution as compared to India’s struggle for freedom.[42] Attention must be drawn here to Tadd Graham Fernée’s work, where he compares the European Enlightenment project with the Indian, Turkish and Iranian efforts at transition to modernity, with a focus on the Indian National Movement under Gandhiji’s leadership with its ‘Ethic of Reconciliation as Mass Movement’ as well as the ‘Nehruvian effort after independence’ at drawing on this heritage, towards an ‘Ethic of Reconciliation in Nation Making’.[43] His conclusion is that the Indian experiment at transition to modernity without violence remained much truer to the Enlightenment objectives.

Bhattacharjee has done us a favour by quoting extensively from Octavio Paz,[44] the great Mexican poet, thinker, diplomat and Nobel Laureate, who was also Mexican ambassador to India in Nehru’s time, showing how he very sensitively comprehended what Nehru had ‘discovered’ for himself from Indian tradition and Gandhiji, and very importantly, brilliantly interpreted Nehru and his supposed contradictions. It is well worth repeating them here, if for no other reason but to show how great contemporaries of Nehru saw him in contrast to scholars whom I would characterise as Eurocentric if not colonial and of course, the communal, fake ‘nationalists’ in India.

In a speech delivered in 1966, Paz says:

“It is remarkable that Nehru, in spite of his mainly being a political leader, did not fall into the temptation of suppressing the contradictions of history by brute force or with a verbal tour de passé (sleight of hand). [It] is unique in our world of fanatical Manicheans (those who see things only in black and white) and hangmen masked as philosophers of history. He did not pretend to embody either the supreme good or the absolute truth but human liberty: man and his contradictions…. He was faithful to his contradictions and for this very reason he neither killed others nor mutilated himself”.

Again, he says very profoundly and with a deep understanding of Nehru:

“In contrast to the majority of the political leaders of this century. Nehru did not believe that he had the key to history in his hands. Because of this he did not stain his country nor the world with blood.”

Nehru tried to move towards his goal, what he thought was his historic role with this sensibility. This meant following a path which could be slower, but took people along and did not resort to violence and brute force as many of his contemporaries trying the same transformation did.

Notes

1. See Aditya Mukherjee and Mridula Mukherjee, “Weaponising History: The Hindutva Communal Project”, The Wire, 10 April 2023, https://m.thewire.in/article/history/weaponising-history-the-hindu-communal project; Mridula Mukherjee, ‘History Wars: The Case of Gandhi-Nehru-Patel’, in IIC Quarterly, Volume 49, Summer 2022, Number 1, pp39-41. See also, Aditya Mukherjee, Mridula Mukherjee and Sucheta Mahajan, RSS School Texts and the Murder of Mahatma Gandhi: The Hindu Communal Project, Sage, New Delhi, 2008, an enlarged revised edition forthcoming shortly with Penguin.

2. B. Gopal Krishnan in ‘Kesari’, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) mouthpiece in Kerala, 17 October 2014, see https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india others/godse-should-have-targeted-nehru-says-rss-mouthpiece/ Accessed on 17 August 2021.

3. Times of India, 8 May 2016, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/references to-jawaharlal-nehru-dropped-in-new-rajasthan-school-textbook-congress-cries foul/articleshow/52177280.cms, The Indian Express, 26 May 2016, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/jawaharlal-nehru-erased from-rajasthan-school-textbook-2789754/ accessed on 4 November 2023, 6.41 pm.

4. See for example, Times of India, 30 August 2021, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/other-posters-will-have-nehrus-image unnecessary-controversy-over-issue-ichr-official/articleshow/85735778.cms, accessed on 3 November 2023 7.34 pm. The Hindu, 29 August 2021, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/chidambaram-slams-ichr-for-omitting nehrus-photo-from-poster-celebrating-indias-independence/article36161501.ece, accessed on 3 November 2023, 7.36 pm.

5. For a detailed discussion on the close link between colonialism and communalism, see chapter 10, “Colonialism and Communalism: A Legacy Haunting India Today”, in Aditya Mukherjee, Political Economy of Colonial and Post-Colonial India, Primus Books, Delhi, 2022.

6. “Jawaharlal Nehru’s Historical Vision” in Irfan Habib, The National Movement: Studies in Ideology and History, Tulika Books, New Delhi, p. 38-39. See for a similar appreciation of Nehru as Habib’s, Joachim Heidrich, “Jawaharlal Nehru’s Perception of History”, (Mimeo.) in a fascinating Seminar on ‘Jawaharlal Nehru as Writer and Historian’, in which large number of scholars from all over the world participated, organised by the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund and Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi, 23–26 October 1989.

7. “On Understanding History”, Inaugural address to the silver jubilee session of the Indian Historical Records Commission, 23 December 1948, Jawaharlal Nehru’s Speeches, Vol. 1 (1946-1949), Publications Division, Government of India, New Delhi, 4th edition 1983, pp. 354, 357–58.

8. Habib, Jawaharlal Nehru’s Historical Vision, p. 40.

9. “On Understanding History”, 1948, p. 358.

10. The discussion on the Somanatha and the quotation from K.M. Munshi is from Romila Thapar, ‘Perspectives of the History of Somanatha’, Umashankar Joshi Memorial Lecture, 29 December 2012 and Somanatha: The Many Voices of a History, Penguin, New Delhi, 2003.

11. Jawaharlal Nehru, Discovery of India, (first published The Signet Press, Calcutta 1946), Penguin, Gurgaon, 2010, pp. 250–54. All references to Discovery are from this edition.

12. Amartya Sen expands on this theme in many of his writings. See for example, Amartya Sen, The Idea of Justice, London, 2009, Ch.15, pp. 321–25 and Amartya Sen, The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture and Identity, London, 2005.

13. Discovery, p. 263. A song written and composed by Khusrau: “Chaap Tilak Sab Chheeni re Mose Naina Milaike”, for example, is sung till today by millions across religions in the Indian subcontinent, including Pakistan and Bangladesh, till today.

14. Discovery, p. 51.

15. Discovery, p. 254 and “Importance of Archeological Study”, Speech delivered at the Centenary celebrations of the Archaeological Survey of India and the International Conference of Asian Archaeology, New Delhi, 14 Dec. 1961, Jawaharlal Nehru’s Speeches, Vol. 4, 1957–1963, Publications Division, Government of India, New Delhi, 1964, pp. 179–81. Emphasis mine.

16. Discovery, p. 258.

17. See for example, Romila Thapar, Harbans Mukhia and Bipan Chandra, Communalism and the Writing of Indian History, People’s Publishing House, Delhi, 1969 and Micheguglielmo Torri, “For a New Periodization of Indian History: The History of India as Part of the History of the World”, Studies in History, Vol. 30 (1), 2014.

18. On Understanding History, 1948, pp. 353–54.

19. Ibid., pp. 354–55. Emphasis mine.

20. See chapter 13, “Challenges to the Social Sciences in the Twenty-First Century: Perspectives from the Global South” in Aditya Mukherjee, Political Economy of Colonial and Post-Colonial India, Delhi, 2022, for a discussion on Eurocentric/colonial perspectives continuing to be a challenge in the third world and even among finest historians of the West, including Marxist historians.

21. “A New Perspective of History”, Inaugural Address to the Asian History Congress, New Delhi, 9 December 1961, Jawaharlal Nehru’s Speeches, Vol. 4, 1957–1963, p. 179.

22. “A New Perspective of History”, 1961, p. 178.

23. “On the Understanding of History”, Foreword to a book, 8 October 1933, Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, (hereafter SWJN), 1st Series, Vol. 6, 1979, New Delhi, pp. 199–200.

24. “A New Perspective of History”, 1961, p. 178.

25. For a recent example of this obfuscation see, “Empire and Transformation: The Politics of Difference”, Keynote Lecture by Jane Burbank, New York University, at the 6th International Symposium of Comparative Research on Major Regional Powers in Eurasia Comparing Modern Empires: Imperial Rule and Decolonisation in the Changing World Order, Hokkaido University, Japan, 20 January 2012 and for the development of her argument with sources and citations Jane Burbank and Frederick Cooper, Empire in World History: Power and Politics of Difference, Princeton, 2010.

26. “On the Understanding of History”, 1933, p. 200.

27. The Wire, 19 July 2023, https://thewire.in/history/claiming-india-saw-1000-years of-foreign-rule-trivialises-british-colonial-exploitation accessed on 5 November 2023, 6:11 pm, The Wire, 15 August 2023, https://thewire.in/government/independence-day-modi-speech-slavery-manipur , accessed on 24 August 2023, 9.16 pm. The PM made the same statement addressing a joint session of the US Congress on 22 June 2023,

https://scroll.in/latest/1051436/india-got-freedom-after-1000-years-of-foreign-rule says-narendra-modi-at-us-congress , accessed on 24 August 2023, 9.33 pm. He talked of 1200 years of slavery in his Motion of Thanks to the President’s address to the joint session of the Parliament on 9 June 2014. https://www.firstpost.com/politics/1200-years-of-servitude-pm-modi-offers food-for-thought-1567805.html , 13 June 2014, accessed on 24 August 2023, 10.04 pm.

28. Discovery, pp. 254–55. Emphasis mine.

29. A New Perspective of History, 1961, p. 178

30. On the Understanding of History, 1933, p.199. Emphasis mine.

31. On Understanding History, 1948, p.354. Emphasis mine.

32. On Understanding History, 1948, pp. 354, 356, 357. Emphasis mine.

33. Ibid., pp. 355–56.

34. On the Understanding of History, 1933, p. 200.

35. For example, R.S. Sharma, Romila Thapar, Bipan Chandra, Satish Chandra, Irfan Habib, D.N. Jha, Arjun Dev, Shireen Mooswi, Ranabir Chakroborty, Upinder Singh and so many others.

36. Bipan Chandra outlines the critical shift in Nehru’s thinking and the impact of Gandhiji. He was among the first in the Left to see this shift positively. See his seminal essay “Jawaharlal Nehru in Historical Perspective” in Writings of Bipan Chandra: The Making of Modern India: From Marx to Gandhi, New Delhi, 2012. For a brief summary see my Introduction to the above volume reproduced in Aditya Mukherjee, Political Economy of Colonial and Post-colonial India, Delhi, 2022. More on this aspect later.

37. See Bipan Chandra, “Jawaharlal Nehru in Historical Perspective” …, pp. 113–14.

38. Quoted in Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee, Nehru and the Spirit of India, Gurugram, 2022, p. 181.

39. Perry Anderson, The Indian Ideology, Three Essays Collective, Gurgaon, 2012, pp. 52–53.

40. Bhattacharjee, Nehru and the Spirit of India, p. 21.

41. Bipan Chandra, “Jawaharlal Nehru in Historical Perspective” …, pp. 150–51.

42. See, Tadd Graham Fernée, “The Gandhian Circle of Moral Consideration”, Social Scientist, Vol. 50, No. 11–12, 2022, where he quotes Gandhi comparing the French and Russian Revolution with the Indian struggle.

43. Tadd Graham Fernée, Enlightenment and Violence: Modernity and Nation Making, Sage Series in Modern Indian History, New Delhi, 2014 and Tadd Graham Fernée, Beyond the Circle of Violence and Progress: Ethics and Material Development in India and Egypt, Anti-colonial Struggle to Independence, Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla, 2023.

44. Bhattacharjee, Nehru and the Spirit of India, pp. 16, 18, 181.

(Courtesy: The Wire.)