Transcript

Amy Goodman: Today, March 8th, marks International Women’s Day around the world, celebrating half the planet’s population, even as many continue to face discrimination, violence and abuse. Some women are using the day to speak back to corporate cooptation of the holiday on social media by posting about pay gaps at places that pay men more than women. Women and their allies are also gathering in person for events big and small. Millions are demonstrating in Spain, which on Tuesday passed a new gender equality mandate for large companies, civil service and government institutions. Meanwhile, in Pakistan, women marched despite threats by conservative groups to stop them by force. And neighboring Afghanistan is now the world’s most repressive country for women, according to the United Nations. We’ll talk about that later in the show. We’ll also talk about the women-led protests in Iran and calls to address the abortion ban crisis in El Salvador and other countries.

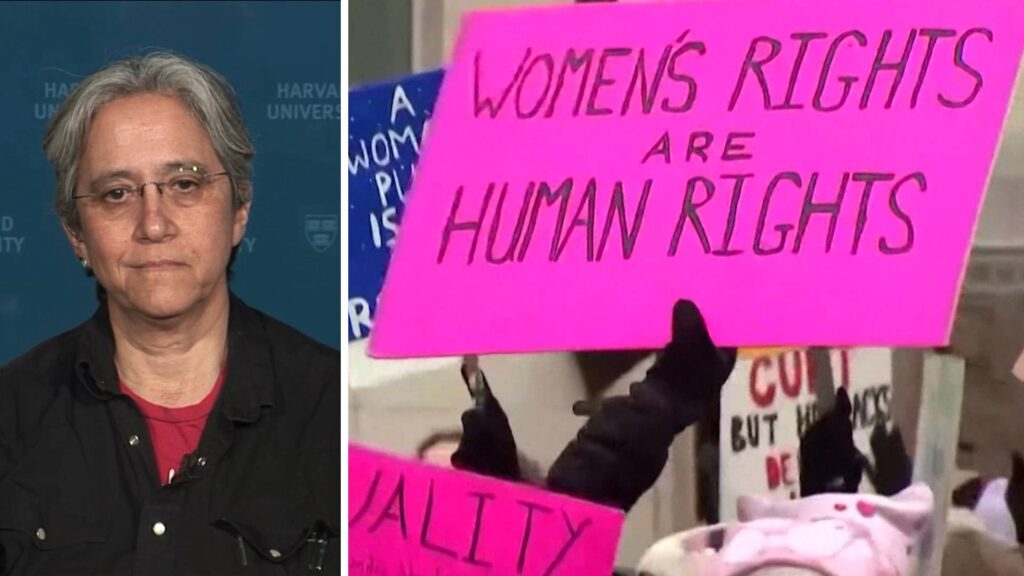

But we begin here in the United States, which ended the constitutional right to abortion last year. We begin with Nancy Krieger, renowned professor of social epidemiology at Harvard University School of Public Health, director of the Interdisciplinary Concentration on Women, Gender, and Health. She’s also co-founder and chair of the Spirit of 1848 Caucus in the American Public Health Association, which links social justice and public health. She gives the introduction each year to the school’s International Women’s Day event by laying out its radical history.

So, Professor Krieger, welcome to Democracy Now! And teach. Tell us about this day’s roots in socialism, and more.

Nancy Krieger: Thank you very much for having me. And it’s wonderful to be with you.

And, yes, International Women’s Day has a very long progressive history that’s often not well known. And we have been celebrating it now for over 11 years at the School of Public Health with the Women, Gender, and Health concentration to bring that history back to life so that people can make the connections.

So, the very first International — National Women’s Day that took place, actually, in 1909 in the U.S., it was on the last Sunday in February, and it was organized by American socialists tied to the labor organizing that was going on at that time and also the push for women’s suffrage. One year later, Clara Zetkin made a proposal for an International Women’s Day at the second-ever International Conference of Socialist Women, which was held in Copenhagen. And they made good on that promise in 1911, when there was the first European International Women’s Day that was held in Vienna. It was organized by socialist and communist women at the time. And it was held, importantly, on March 18th. This was to be in commemoration of the 40th anniversary then of the Paris Commune, which had started on March 18th in 1871, a radical experiment, among others, in democracy, and it was violently suppressed May 28th. And so they were remembering it 40 years later, just as we in 2023 would remember an event in 1983, which is obviously back to the Reagan presidency in the United States, among other things, not that far ago. And then, what happened is, that same year it was observed in other countries, including Denmark, Germany and Switzerland. And by 1917, March 8th became the official day for International Women’s Day.

And that date, March 8th, corresponded to February 22nd, which in the Gregorian calendar was equal to March 8th, which was the date of a huge demonstration in Russia against the tsar, led by women. It was about food and wages and rights. And that was a key demonstration that led to the overthrow of the Russian tsar. And also, the provisional government that came into power right thereafter immediately, among other things, enacted suffrage for women, which was actually three years before the United States. So, that’s when International Women’s Day really began to take off, and it became established as a holiday in what was then the Soviet Union in 1922.

And it was key hearing earlier in your broadcast about demonstrations in Spain. In 1936, there was an enormous International Women’s Day demonstration led by La Pasionaria, who was fighting for protecting the Spanish Republic against the fascist government at that time.

So, basically, until — from 1945, after the war, to ’66, International Women’s Day was pretty much observed only in communist countries and became, in effect, a kind of Mother’s Day. It sort of lost the radical edge that it had at the beginning. But it was rediscovered in 1967 by a group of women in Chicago in the Chicago Circle, which was a women’s liberation consciousness group. And they began to call for reviving the history of International Women’s Day. And it was eventually picked up in 1975 by the U.N. and became an internationally recognized day. So, here we are in 2011, it was the 100th anniversary of International Women’s Day, still a lot of the agenda unmet from what was demanded a hundred years prior. And now here we are today in 2023. It’s effectively its 112th anniversary.

Nermeen Shaikh: Thank you so much, Professor Krieger, for that history. And even as many are not aware of its socialist origins, as you’ve pointed out, could you talk about how it’s been linked to other causes for social justice, not just here in the U.S. but also across the world, including, of course, as we were mentioning earlier, reproductive justice and rights?

NK: So, International Women’s Day has its roots in saying that women and their families, however they are defined, however the women are defined, should have the ability to thrive, to engage productively in the world, to live joyful lives. And that means having children or not, as makes sense, and having the opportunities for those children to thrive. So it’s always been tied to demands around reproductive justice, as you’ve just mentioned, around labor rights, and about good jobs and about access to education and about safe and sustainable communities and more. So, it’s inseparable from all the other demands.

And that’s what was always the original spirit, when you think about who was stepping out, asking and demanding for political enfranchisement, to be able to have their lives and their views represented in government and pass laws and legislation and policies that protect people’s right to thrive, and is crucially important, right now very much so through the framework of reproductive justice, which was first articulated before U.N. conferences back 20-odd years ago, particularly by Black feminist organizations and leaders in this country. It was linking, again, not just simply reproductive choice but reproductive justice, to be able to have the conditions in which people can thrive, and that means for the children that they have, and it also means if they choose not to have children.

So these are very connected struggles, and it can’t be unlinked from other struggles for health justice, whether about environmental, climate justice, you name it. They come together. They’re embodied by people, and they’re embodied very much through what we see in the maternal and reproductive health data that you see, that are wildly different across different social groups, racialized groups, economic groups, in the U.S. and throughout the world, between and within countries.

NS: And, Professor Krieger, could you talk about what’s happened, in particular, as we mark this day in 2023, what the impact of the pandemic has been on exacerbating inequities with respect to women, not just in terms of health but also in the workplace, as a result of what happened during the pandemic?

NK: Certainly. The COVID pandemic effectively ripped the Band-Aid off, as it were, to reveal wide inequities that were already known by those paying attention to them and, above all, those living and experiencing them. And these inequities were violently shown during the first, particularly, year of the pandemic, before there was access to any vaccine and while there was new work going quickly underway to try to figure out how to reduce mortality amongst those who were affected.

And so, what happened was that the first peoples that were worst — most likely to die — particularly I can speak to the U.S. data — were people that were both the frontline workers, people that were deemed, quote-unquote, “essential,” that had to show up at work but were ultimately treated as expendable, predominantly low-income workers of color, and, of those, many in caring occupations, which are disproportionately by people who are considered to be women. And so you saw much higher mortality there, plus also high mortality amongst people that were in congregate homes, elderly homes, nursing homes, which were understaffed, with workers who were overworked, again predominantly low-income of color and again predominantly women in those occupations, and then they and people in those nursing homes at high rates.

So you saw big inequities in the COVID mortality. And really, back then, it was through excess deaths, understanding them, because there wasn’t good COVID testing for everyone. And that’s still true now. Not all COVID deaths are actually accurately recorded. And there are differentials by racialized group and economic group in getting good data to understand the impact of the inequities in who was lost. And then, obviously, it’s not just about the loss of the individuals who died; it’s all the people and their families and networks, to understand — you have to understand the ripple effects that this has put through, understand the impacts, what it means on the kids who have been orphaned, what it means when there are no caregivers for elderly if their children have died. So, the toll continues.

AG: Professor Krieger, you’re a renowned professor of social epidemiology. I think the world came to understand how to pronounce the word “epidemiologist” over these last three years. And so, if you can talk about reproductive healthcare? Now, we just had in our headlines today five women suing Texas after they were denied abortions, even as their pregnancy posed serious risks to their health and were not viable, one woman describing how no Texas OB-GYN would perform an abortion, which meant she went into sepsis, which meant she may not be able to have another child, when that’s all she wanted. We’re going to also talk about the ban on abortion in El Salvador. If you can talk about reproductive rights, the attack on it, and why this year you’re celebrating a birthing center in Roxbury?

NK: Sure. So, reproductive justice encompasses reproductive rights and goes beyond that, but reproductive rights are very essential. And that means the capacity to access the appropriate medical care for what one’s reproductive needs are. Those can be needs that involve in vitro fertilization. They can be needs that involve not having children and getting access to appropriate contraception. They can be needs that involve actually terminating a pregnancy, including abortion. These are all actual normal healthcare procedures. They’re necessary for people’s health, period. And that affects the health of everyone who’s around people, because people can be very worried about loved ones when they can’t get the healthcare that they absolutely need.

So, these fights are there, and they’re tied fundamentally to issues around the fights around gender ideology. Gender ideology has been castigated by people that are conservative, right-wing, often from a religious fundamentalist standpoint, that somehow decree that there’s no such thing as gender, there’s only sex. And then, at the same time, they want to have people having babies, but they don’t want them to have abortions, but they actually are also not tied to understanding that reproductive autonomy actually is a crucial part of whether one has children or not.

So, these are the attacks that are underway. It’s a global phenomenon. It’s playing out particularly in the U.S. in legislatures, particularly those that have seen a predominance of conservative politicians voted in. And that’s also partly courtesy of all kinds of gerrymandering that’s been going on. So it can’t be seen as an expression of the, quote-unquote, “people’s will,” because actually popular public opinion really supports, in many states, all the states, rights for reproductive choice, rights for reproductive justice. And that’s also shown in terms of the recent attempts to — of legislatures to rule out and have popular referenda, say, “No, actually, we should be still protecting reproductive rights.”

AG: Well, as we —

NK: So, what we do at our school — just to say quickly — is we’ve had this International Women’s Day celebration. And this year what we wanted to do was have the featured speaker, Nashira Baril, who’s been key to organizing what’s going to be opening as Boston’s first neighborhood birthing center, geared to women who have traditionally been excluded and marginalized by healthcare systems. It’s going to open in Nubian Square in Roxbury. And we wanted to have something where it both represents the struggle, the radical history of reproductive justice and fighting for it, but also because it’s about joy, and it’s about bringing people into the world, bringing new little ones into the world, in a context that’s caring, welcoming and inclusive, and that that’s part of the reproductive justice fight, too.

AG: And finally, Professor Krieger, I know every International Women’s Day, wherever you are, you sing “Bread and Roses.” And as we wrap up this segment, we’re about to play that for our music break. Can you talk about its radical roots? What is “Bread and Roses”?

NK: Yeah, so, we close our ceremony that we have every year here with that song, because it comes, actually, from very close to Harvard. It was in Lawrence, Massachusetts. It was the big strike that was held by immigrant groups, with over 28 different languages being spoken. The International Workers of the World were involved, the Wobblies. The Songbook was there. It gave rise to the song “Bread and Roses,” which is about what the women were in fact fighting for. And that song itself comes from, actually, a letter that was written to Mother Jones, who was a legendary organizer, before she died, which was saying, about fighting for bread and roses, it’s both. And then, the person who was writing, a radical reporter at the time, covering the Lawrence march, said that “Beware the movement that generates its own songs,” because songs do carry the spirit of the people, and that’s what “Bread and Roses” was about. And that’s why we try to teach it to people every year.

AG: Well, I want to thank you so much for being with us. And, of course, as Emma Goldman says it, “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution.”

(Amy Goodman is the host and executive producer of Democracy Now!, a national, daily, independent, award-winning news program airing on more than 1,100 public television and radio stations worldwide. Nermeen Shaikh is a broadcast news producer and weekly co-host at Democracy Now! in New York City. She worked in research and nongovernmental organizations before joining Democracy Now! Courtesy: Truthout, a US nonprofit news organization dedicated to providing independent reporting and commentary on a diverse range of social justice issues.)