The latest, June quarter gross domestic product (GDP) figures for fiscal year (FY) 23 delivered some much-needed grist for the BJP’s spin mills. Prima facie, the numbers look impressive and, to nobody’s surprise, the party machinery is leaving no stone unturned in trumpeting the figures as evidence that the Modi government is indeed grafting together an impressive growth narrative for India. However, the catch here is that under the window dressing of the GDP figures, the economy is unmistakably tottering and the growth trajectory since the pandemic has been ramshackle at best.

Contrasted with the 16.2% growth rate projection given by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and a median projection of 15.2% by economists surveyed by Reuters, the latest quarter growth rate numbers surprised everyone by coming in lower at 13.5%. A real GDP growth rate of 13.5% sounds incredible and this growth spurt can be attributed to the second wave of COVID-19 that devastated the subcontinent during the same quarter last year. Naturally, economic activity in large swathes across India took a beating and real GDP figures tanked. This made for a low base compared to which the Indian economy registered a 13.5% real GDP growth rate in the last quarter.

As for the claim of the Indian economy pipping the UK to become the fifth largest economy, the latest GDP figures might not be the best compass through this economic terrain. Consider, for a moment, the per capita GDP gulf between the two nations, which is staggeringly large and truly embarrassing for India. For the UK, per capita figure of $47,000, India’s per capita figures scrape in at barely $2,500. In any case, the GDP is a measure of income and not wealth. Reliance on GDP figures as an indicator to suggest that India’s wealth has shot up or its poverty levels have plummeted is a disingenuous ploy that massages economic statistics for the larger goal of creating a sellable narrative. India’s GDP figures could keep climbing upward but it would never be an economic indicator suggesting an equitable redistribution of wealth. The GDP figures can continue to climb higher even if the top 1% prospers at the cost of the 99%.

The credit rating agency India Ratings, in a note dated September 8, cautions against drawing glowing conclusions about the Indian economy considering the low base of FY21 and FY22. The real state of affairs is revealed once comparisons with the pre-pandemic scenario are made – and the picture that emerges is depressing.

“In the aftermath of COVID-19, the analysis of [year-on-year or YOY] growth,” the research note states, “does not provide a true picture of the economic recovery due to the low base of FY21 and FY22. Therefore, a better way to assess the recovery in GDP/gross value added is to compare the growth trend taking the pre-COVID period as a base. When done so, the GDP shows a [compound annual growth rate or CAGR] of just 1.3% during 1QFY20- 1QFY23 as against 6.2% during 1QFY17-1QFY20. Among all the sectors, the CAGR growth of the services sector shows the sharpest decline to 1.0% during 1QFY20-1QFY23 from 7.1% during 1QFY17-1QFY20, implying that the recovery in the sector is still weakest”.

If that isn’t enough bad news, account for the fact that the real wage growth in India has sunk into negative territory. With inflation wreaking havoc, every single rupee of a common man’s wages has lesser purchasing power now than a few years back.

“The household sector which accounts for 44-45% of the GVA saw its nominal wage growth decline to 5.7% during FY17-FY21 as compared to the 8.2% growth rate recorded during FY12-FY16. This means that the wage growth in real terms is close to just about 1%. Since much of the growth in consumption demand is driven by the wage growth of the household sector, a recovery in their wage growth is going to be critical for a sustainable and durable recovery in private final consumption expenditure and overall GDP growth in FY23. Even the recent trend in wage growth at the rural and urban levels alludes to an erosion of the purchasing power of households. At the nominal level, the wage growth in urban and rural areas was 2.8% YoY and 5.5% YoY, respectively, but in real terms (adjusted for inflation) was about negative 3.7% and negative 1.6% in June 2022.” the India Ratings research note states.

Scarce Regular Salaried Jobs

The government has discontinued the publication of consumer expenditure surveys that would be a proxy for household incomes. However, the Periodic Labour Force Surveys (PLFS) do give estimates of the earnings of the three basic types of workers based on their recall of the preceding week’s work status. These three categories are regular salaried workers, casual daily wage earners and self-employed persons.

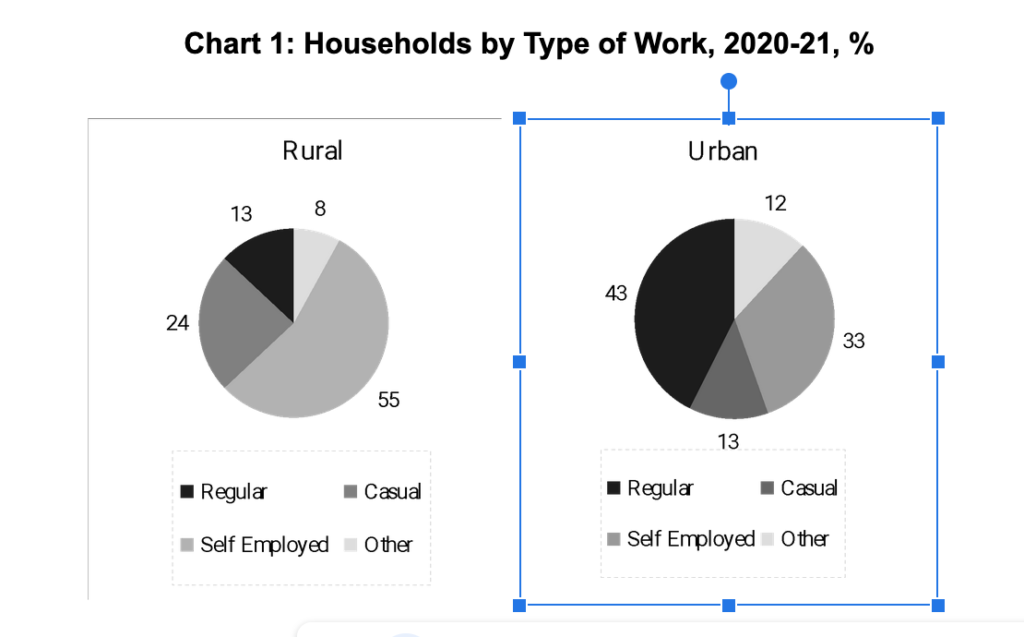

The latest PLFS annual report published in June this year covers the period April 2020 to March 2021. According to this report, in rural areas, the predominant share of households (55%) is self-employed, largely in agriculture. This is followed by casual labour (24%), which is often seasonal and irregular work on daily wages. Regular, salaried workers make up just 13% of rural households. (See chart 1)

In urban areas, regular workers comprise 43% of households while self-employed are 33%. Casual workers are 13%.

Earnings Meagre in All Jobs

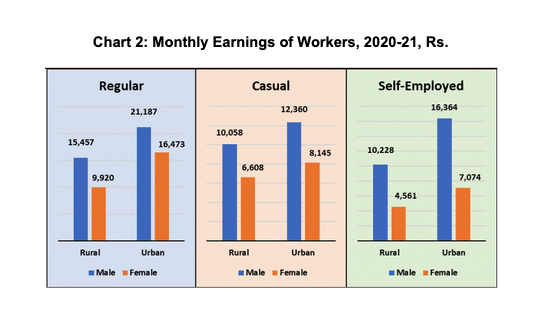

Let us look at the average earnings of these three types of households, shown in the chart 2. Besides the urban regular male workers who get just over Rs 21,000/month, none of the other categories of workers earn a sufficient wage for a dignified life, free of want and struggle. What is striking in this chart is the deep chasm between rural and urban incomes, male and female incomes, and incomes of regular salaried workers and casual workers or even self-employed earners.

In rural areas, the largest category of earners is the self-employed, mostly farmers. In this work, male earners get Rs 10,228/month, while female earners get less than half that (Rs 4,561). Casual workers who work for daily wages and suffer very onerous working conditions are the least paid of all. Even in urban areas, a male casual worker will earn just Rs 10,058/month, while the female worker will get just Rs 6,608. In urban areas, earnings are slightly better at Rs 12,360 for men and Rs 8,145 for women. These monthly wages for casual workers are projected from daily earnings data that was collected in the PLFS. In reality, there will be days when there is no work interspersed with days of work.

The extremely low levels of earnings of women workers across the board – whether rural or urban, whether casual, regular or even self-employed – reveals one of the reasons behind the low work participation rates of women in work. With this kind of wages, and with all the other difficulties in going out for work, including carrying the double burden of having to do all the work at home, too, it is not surprising that women are actively discouraged from working.

Actual Chances of Economic Recovery in Near Future Dim

Despite the celebration of higher economic growth in recent months, declining incomes mean that people at large do not have sufficient buying power in their hands. These households contribute substantially to economic output, making up 44-45% of Gross Value Added (GVA). Persistent low incomes mean their contribution to aggregate demand is going to be very low. This, in turn, means that the chances of any economic recovery are dim because there will not be sufficient demand in the economy.

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s homilies to India’s corporate sector to invest more (and thus create more jobs) are going to fall on deaf ears because the corporate sector is enjoying all the concessions and tax cuts that the Modi government has offered without having to invest more. It will not invest more because who will buy? People just don’t have the buying power in their hands.

(This article has been compiled by us from Kaushal Shroff’s article in Newsclick and an article in The Wire by The Wire Staff.)